REVIEW: Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Samuel

The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Samuel—The Making of the Monarchy, edited by David Arnovitz et al. (Koren Publishers, 2021), 505 pages

The Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel: Samuel—The Making of the Monarchy, edited by David Arnovitz et al. (Koren Publishers, 2021), 505 pages

We welcome the publication Samuel: The Making of the Monarchy, the second volume of the new Koren Tanakh of the Land of Israel series. As I discussed in my review of their first volume on Exodus, this new undertaking is written from an Orthodox perspective, utilizing contemporary scholarship as a tool for understanding God’s word. The essays are generally presented judiciously, rather than reaching conclusions that exceed the biblical or archaeological evidence. The volume is not a comprehensive commentary on Samuel, but rather a companion that focuses on archaeology, geography, and the languages and realia of the ancient Near East that elucidate aspects of the biblical text. There are brief articles and glossy photographs, maps, and illustrations that bring these areas to light.

Many essays note that other ancient Near Eastern cultures referred to similar elements as those in Tanakh. For example, other ancient Near Eastern people discussed barrenness, breastfeeding, bribery, sacrifice, eulogies, tearing garments out of mourning, and so on. Noting these parallels does not substantially add to our understanding of Tanakh, but rather supplies context. Similarly, many geographical entries identify locations in the narratives, valuable information in its own right but often without impacting on the meaning of the passage.

The most productive aspects of the volume are when the scholarship clarifies matters we would not have otherwise known or pinpoints contrasts between Israel and surrounding cultures to highlight the revolutionary contributions of Tanakh. In this review, we will consider a few salient examples from the variegated areas of scholarship that may contribute to our learning of the Book of Samuel.

David dances in front of the Ark. Francesco Salvatti (1552-54), Saccheti Palace, Rome. © The Yorck Project.

Linguistics

Amnon asks his sister Tamar to prepare levivot for him. These may have been heart-shaped pastries (from Hebrew lev, for heart), fittingly reflective of Amnon’s lustful love of Tamar. In Akkadian and Mesopotamian, types of bread were given names indicating that they were shaped like various body parts, such as akal ubanatum (finger-shaped bread), ninda rittu (hand-shaped bread), etc. Akkadian had akal libbu, and Mesopotamian had ninda libbu, for heart-shaped bread (310).

David dances in honor of the Ark. The obscure term mekharker appears in II Samuel 6:14, 16, the only occurrences of this verb in Tanakh. The parallel narrative in I Chronicles 15:29 utilizes the familiar word for dancing, merakked. The term mekharker seems related to the Ugaritic krkr, twist, meaning that David twisted his body or whirled around (262).

Archaeology

After Samuel tells Saul that God has rejected his monarchy as a consequence of his failures in the war against Amalek, Saul grabs the hem of Samuel’s garment and it tears. Samuel converts the tear into an additional prophetic sign that God has torn the kingship from Saul (I Samuel 15:27-28). Grasping at the hem of a garment was an expression of loyalty and submission in the ancient Near East. Saul’s grabbing of Samuel’s hem may have conveyed submission to the prophet, rather than merely a desperate “please don’t leave me!” The accidental tear, however, ironically turned into a further sign of rebellion and Saul’s future downfall (130).

David strikes Goliath with a stone from his sling. Archaeologists have discovered ancient slings from Egypt. A sling contains a central pouch for the missile, attached to two strings. One string has a loop tied to one end, into which the slinger keeps one finger when twirling the strings. Once the sling is going fast enough, the slinger removes his finger from the loop, causing the missile to fly towards its target. Studies have shown that an ancient slingshot could shoot a stone up to 400 meters (around 1300 feet) at 160 kilometers (100 miles) per hour (143).

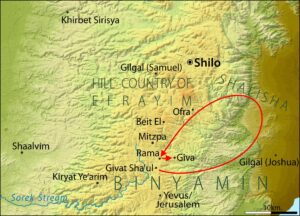

Geography

The Philistines assemble at Afek in I Samuel chapters 4 and 29, because it was the closest strategic location under their control (on their northern border). Afek is on a route that allows crossing the Yarkon River without climbing into the hills of Shomron (36).

Saul searches for his father’s lost donkeys. Based on the locations we can identify, Saul and his servant walked at least 20 kilometers (12 miles). This geographical information increases our appreciation of the extent to which Saul honored his father (79).

Unique Features of Tanakh

In the ancient Near East, people did not know what their gods expected of them. The deities were capricious, and often disagreed with one another. In contrast, God explicitly states what He expects of Israel, and if they sin, how to return to Him. This clarity enables the process of repentance, which was unique in the ancient Near East (61).

Ancient Near Eastern prophets spoke almost exclusively to kings, about matters of state. Only Israel’s prophets speak to the nation as a whole, since God is concerned with the entire nation serving Him in a covenantal relationship (68).

Unlike the atrocity of Saul’s massacre of the priests of Nob, nowhere in extant ancient Near Eastern texts is there a report of a king killing the legitimate priests of his own deity. For that matter, nowhere in ancient Near Eastern literature do we hear of mere soldiers refusing to obey a king’s command, as Saul’s soldiers refused to murder the priests (170).

Nathan excoriates David after David’s sin with Bathsheba and Uriah. There is no extant record of an ancient Near Eastern prophet rebuking a king for immorality. Only Tanakh insists that the king is not above the law (301).

Excurses

Throughout the volume, there are excurses that provide valuable background into broader issues. For example, the excursus on Jerusalem at the time of King David (248-249) analyzes the debate among archaeologists regarding the extent of the Davidic monarchy in the tenth century B.C.E. There also is a useful methodological excursus on archaeological findings from Edom (282-283). Edomite engagement in copper production has enabled scholars to reconstruct a powerful nomadic kingdom. For a long time, archaeologists wrongly assumed that ancient nomadic peoples resembled contemporary Bedouins. They insisted that only great empires could be responsible for large-scale industry. The evidence from Edom demonstrates that archaeology cannot uncover many artifacts from nomadic or seminomadic cultures, but this silence does not prove that the culture was insignificant. Similarly, archaeology is an inadequate tool for assessing the historicity of biblical narratives pertaining to a mixture of settled and nomadic people.

Criticisms

Although the authors generally present their sources in a manner that gives a balanced reading to the biblical text and their ancient Near Eastern sources, there are a few exceptions. To cite one notable example, Michal’s marriage to Palti (I Samuel 25:44) and subsequent return to David (II Samuel 3:13-16) is halakhically perplexing, given that David and Michal still were married when she and Palti were “wed.”

The authors attempt to solve these difficulties by citing laws of the ancient Near East (238). If a husband abandons his wife and the wife has the means to live independently, she may not remarry (Laws of Hammurabi #133, Middle Assyrian Laws #36). However, if the woman has no means to support herself, then the reason behind her husband’s absence determines his wife’s status. If his absence is due to political, civil, or personal reasons, and the wife remarries, she remains with her second husband. The husband is viewed as having abandoned his wife (Eshnunna Laws #30, Laws of Hammurabi #136, Middle Assyrian Laws #36). In contrast, when a husband is unwillingly absent, such as if he is kidnapped or taken captive, then his wife is viewed as belonging to her first husband even if she marries a second person (Laws of Hammurabi #145, Middle Assyrian Laws #45). She must return to her first husband upon his return, even if she already has children with the second husband.

Applying these laws to our instance: Since David fled Saul, he could view his abandoning Michal as against his will, so Michal would be required to return to him. However, Saul may have viewed David as trying to undermine him, and his departure was motivated by politics. Therefore, Saul could view Michal’s marriage to Palti as legitimate, since David abandoned her. Abner and Ish-bosheth, on the other hand, viewed David’s request as legitimate, and returned Michal to him.

First, the authors assume that the Israelites followed Near Eastern laws, as opposed to Torah law, which views Michal’s marriage to Palti as adulterous (and therefore we require some other halakhic explanation, as proposed by the Talmud and later classical commentaries (see, e.g., Sanhedrin 19b; Rashi, Radak, Ibn Caspi on I Samuel 25:44). However, a more substantial difficulty with their analysis is that Michal was a princess, and presumably had the means to live independently of David’s home. According to the ancient Near Eastern laws cited, Michal would be required to remain in David’s house and was not allowed to marry another man. It appears that the analysis presented runs against both the laws of the Torah and against the cited ancient Near Eastern conventions.

Conclusion

The high-quality scholarship, coupled with the engaging presentation, make this volume and the series as a whole a valuable companion for Tanakh study. Readers of all backgrounds should mine this book for the many treasures it contains. We look forward to the publication of future volumes of the series.

Rabbi Hayyim Angel, a member of TRADITION’s editorial board, is the National Scholar at the Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals and serves on the Bible Faculty, Yeshiva University.