REVIEW: Terra Incognita

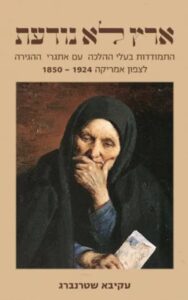

Akiva Sternberg, Eretz Lo Noda’at [Hebrew] (Terra Incognita: Halachic Challenges of the Jewish Immigration to America 1850-1924) (Jerusalem, 2023), 638 Hebrew + 48 English pages

Jews began settling in the New World by the mid-17th century, but it would take two centuries before Abraham Rice was appointed as the first ordained rabbi to be appointed to a synagogue position in the United States. Even after the arrival of an American rabbinate, the locus of halakhic authority remained in Europe for many decades to come. Clearly, Jews in North America maintained a varied and often tenuous relationship to observance—but where did they look for halakhic guidance and pesak?

Akiva Sternberg’s Eretz Lo Noda’at surveys some two hundred halakhic responses authored by various rabbis, most of them from Eastern Europe, who were asked to present their opinions on matters which arose due to the great wave of Jewish migration to America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While the hefty book covers four major topics in as many chapters, this review will focus on the first which takes up the case of Jews who were born and raised in traditional European families in the Old World, but who faced many difficulties in maintaining their former lifestyle once arriving on American soil. (The book’s three other chapters deal with marital issues, particularly the validity of Gittin, Agunot, and Halitza).

Akiva Sternberg’s Eretz Lo Noda’at surveys some two hundred halakhic responses authored by various rabbis, most of them from Eastern Europe, who were asked to present their opinions on matters which arose due to the great wave of Jewish migration to America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While the hefty book covers four major topics in as many chapters, this review will focus on the first which takes up the case of Jews who were born and raised in traditional European families in the Old World, but who faced many difficulties in maintaining their former lifestyle once arriving on American soil. (The book’s three other chapters deal with marital issues, particularly the validity of Gittin, Agunot, and Halitza).

I will not focus on any of the specific halakhic issues examined or on the way in which they were or were not resolved, nor will I assess the author’s capabilities in analyzing them. Rather, in a nutshell, I hope to lay out how halakhic responsa can shed light on the otherwise obscure daily life of Jewish immigrants to America and their struggle to maintain an observant lifestyle.

The idea that halakhic responsa can be used as a historical source is not new. Yet due to their sporadic and inconsistent nature they should only be used when no better sources are available, such as is the case for much of Medieval Jewish History, as shown by Haym Soloveitchik. In that sense the various cases and halakhic discussions presented in the book’s second, third, and fourth chapters were not unique to America and resulted from the great geographical distance between the parties involved; the inexperience of many communal rabbis in dealing with halakhically complex cases; and their lack of expertise in the proper writing of Gittin.

However, as a historian of Jewish Orthodoxy, it was Sternberg’s first chapter that captured my attention. It depicts the stories of many traditional or observant Jews who might have been aware of the challenges they would face upon immigrating, yet were not prepared for those challenges in reality. These began with “minor” or one-time violations of the halakha when they had to board a ship on the Sabbath. It continued with other “small” violations such as muktzeh or carrying in the public domain on the Sabbath, because no eruv was available. Another type of “minor and rare” violation was manifested in the minuscule number of private Sukkot or availability of lulav and etrog, making fulfillment of those observances nearly impossible.

A more significant challenge that the European immigrants faced in their new country was the fear that their children will not follow the traditional lifestyle, with an incipient fear of intermarriage or conversion always present. This resulted from the fact that all children were obliged to attend officially recognized schools that taught secular studies, while attending traditional education in a Talmud Torah or even Sunday school cost money that not all Jews could afford. The fact that the children no longer observed the halakha led to other challenges. One of which was how can observant parents share the same meal with their children who were Sabbath violators.

While these challenges related to individuals, other problems concerned the whole community of observant Jews. Such was the question of kosher meat as some of the shohatim did not observe all the mitzvot, including some of the basic ones. A different and significant sort of challenge was the workplace. This presented all sorts of halakhic questions: Is it permissible for Jewish tobacco shop owners to install a typical wooden Indian statue in front of their store? Did merchants who allowed their customers to pay in installments violate the law forbidding interest? Yet, the major challenge was the fact that in those years Saturday was not a day of rest, and many Jews, either self-employed or hired workers, were forced to work on the Sabbath in order to retain their jobs or businesses. The author presents this dilemma using an original citation in English:

[Before coming to America] I had resolved that I would not desecrate the Sabbath or any part of Judaism. I would rather die of hunger than lose my Judaism […]. But my wife could not resist the temptation to break the Sabbath. I would go to the synagogue to pray, and she would open the store […] I could not tolerate it. We started to fight and tore each other like cats. We came close to separating, until we gave up the store […] in which I had labored for several years (96).

Unlike this family, many Jews were unable to find other jobs that did not require them to work on the Sabbath. This led to another question of whether otherwise observant Jews who were forced to desecrate the Sabbath should be counted when establishing a minyan. Another situation involved cases when the father was an observant business-owner but his children, who no longer observed the halakha, kept the store open on the Sabbath.

The author, an independent scholar who had a distinguished career as a high-placed bank executive, has published several books on the history of halakha, and characteristically presents the various cases he cites in great detail. The list of sources at the end of the book reveals how meticulous he was in collecting the various responses and the main text presents his interpretations of those halakhic responsa. While noteworthy for its organization and marshaling of so many sources, especially many which would have otherwise gone unknown to many readers, the book suffers from several shortcomings. If it is intended for readers who are familiar with responsa literature, then many of the detailed explanations are redundant. On the other hand, if it is pitched to a broader readership, then the author might have explained certain concepts or simply unpacked the myriad abbreviations and acronyms in the text. (As with so many books today, especially a self-published volume such as this, additional proofreading would reduce the number of typos.)

Regardless of these small defects, this is an important book to any scholar interested in the history of halakha, and particularly to scholars interested in the history of Orthodox Judaism in America. Although the book contains a 40-page English summary, I hope the author will publish a full English edition, or at least a version that concentrates on the book’s first chapter.

Menachem Keren-Kratz, an independent scholar, completed doctorates in both Yiddish Literature and Jewish History. His most recent book, Ha-Kanai, a biography of the Satmar Rav, was published by Zalman Shazar Center. His forthcoming book is Jewish Hungarian Orthodoxy: Piety and Zealotry (Routledge Press).

1 Comment

There were Ashkenazi and Sephardic Orthodox congregaions with European and mostly British-trained rabbis, and slome immigrants did ask for help from them.