REVIEW: The Eliezer Berkovits Megillah

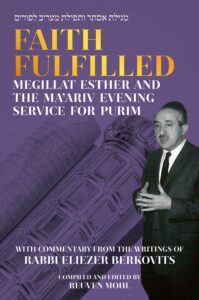

Faith Fulfilled: Megillat Esther with Commentary from the Writings of Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits, compiled and edited by Reuven Mohl (Urim Publications), 156 pages

Everything about Purim evokes excitement. The festivities and activities aim to invigorate the body and the mind. The four mitzva obligations of the day, giving presents to friends and sustenance to the poor, the grand festival banquet, and of course the reading the Megillat Esther, all enhance the miracle of Jewish salvation from genocide in the Persian kingdom of Ahashverosh. Among other books, notably the Passover Haggadah and Pirkei Avot, Megillat Esther has offered artists and commentators a chance to highlight different perspectives on Jewish tradition. A new work, Faith Fulfilled, presents Jewish readers with an innovative way of looking at both the classic Megillah as well as the thought of Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits, one of the most important and prolific Orthodox Jewish thinkers of the twentieth century.

Romanian-born R. Berkovits (1908-1992) received a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Berlin while pursuing semikha from the Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary. He studied with and remained a close disciple of Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, one of the last century’s foremost halakhists. Berkovits wrote and published works on Jewish thought and philosophy, Holocaust and theodicy, halakha, prayer, Israel, and legal theory while serving as a pulpit rabbi and professor of philosophy at the Hebrew Theological College in Chicago (and many other locales on multiple continents during a peripatetic career). He continued publishing after making Aliya in 1976 and remains one of the most salient voices of Modern Orthodox thought. Rabbi Reuven Mohl, D.D.S., has done a valuable service for the English reader by compiling R. Berkovits’ thoughts on the Passover Haggadah, Faith and Freedom, and now on Megillat Esther in his Faith Fulfilled.

Romanian-born R. Berkovits (1908-1992) received a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Berlin while pursuing semikha from the Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary. He studied with and remained a close disciple of Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, one of the last century’s foremost halakhists. Berkovits wrote and published works on Jewish thought and philosophy, Holocaust and theodicy, halakha, prayer, Israel, and legal theory while serving as a pulpit rabbi and professor of philosophy at the Hebrew Theological College in Chicago (and many other locales on multiple continents during a peripatetic career). He continued publishing after making Aliya in 1976 and remains one of the most salient voices of Modern Orthodox thought. Rabbi Reuven Mohl, D.D.S., has done a valuable service for the English reader by compiling R. Berkovits’ thoughts on the Passover Haggadah, Faith and Freedom, and now on Megillat Esther in his Faith Fulfilled.

Faith Fulfilled is more than a commentary on the Megillah—it is a miscellany comprised of several pieces. Rabbi Berkovits did not write commentaries to the Megillah or Purim prayer service; however, Mohl has collected and collated passages from a wide range of Berkovits’ writings. Faith Fulfilled contains a pieced-together commentary not only to the Megillah but also to the festival Maariv service. Mohl also includes an essay on women reading Megillah and a previously published essay on the kabbalistic notion of tzimtzum and its application in Berkovits’ rationalist thought and writing.

An additional meaningful aspect of the book is the donor dedication by Ncoom Gilbar (Gilbert), which is a beautiful reflection on the experience in post-war America of R. Berkovits and Howard Gilbert, the sponsor’s father. It tells the story of R. Berkovits teaching a night class on Parashat HaShavua in a Reform synagogue outside of Chicago. The donor, Ncoom, tells of his Persian immigrant father attending Berkovits’ class—an experience that led to the elder Gibert joining the Orthodox synagogue founded by Rabbi Berkovits.

Mohl offers a brief biography of Eliezer Berkovits and includes a bibliography at the end of the work listing the various primary literature from which this volume was constructed. In the next section, Mohl presents the Maariv service in Hebrew and English with excerpted commentary from Berkovits’ various works. This section relies heavily, although not exclusively, on a wonderful pamphlet on prayer published by Yeshiva University in 1962. For the bulk of the work, Mohl presents a comprehensive collection of short pieces by Berkovits connected to the text of Megillat Esther with translation. It is unclear whether Mohl translated this section or used an existing version – it appears similar to the 1917 JPS with the supplemented Hebrew text. Again, the reader is treated to sections from a wide variety of Berkovits’ many writings.

Since some of Berkovits’ most well-known works deal with the Holocaust and Holocaust theology, it is not surprising to find many links to those events in the Purim story which tells the tale of an ancient attempted genocide of the Jewish people. In explaining the rise of Haman, Mohl quotes from Between Yesterday and Tomorrow where Berkovits suggests, “People speak of us as ‘the wandering Jew.’ The wandering Jew does not travel alone; he is accompanied by the wandering Amalek. Wherever a Jew may go, Amalek follows on his heels.” (68). This statement bears even greater historical force coming as it does from one of the most important post-Holocaust theologians. The Megillah reflects a motif – Amalek – which haunts us throughout the generations. Further on, near the end of the story, Mohl offers a lengthy passage pondering the seemingly ever-present hatred of the Jewish people (96-98). The heaviness of the Shoah hovers in the backdrop of this entire work and links modern events to those from the biblical narrative.

In the erudite section from Jewish Women in Time and Torah regarding women reading Megillah in public, Berkovits traces and analyzes the sources from the biblical text, through the Talmud and codes, and finishes with his halakhic position. Berkovits argues, based on the most direct understanding of the Talmud, that a woman can read the Megillah in public and fulfill the obligation for both women and men. He quotes the Talmud, “All are obligated regarding the reading of Megilla. All are religiously qualified to read it” (Arakhin 3a.) Since the Talmud suggests that “all” includes women, Berkovits points out that this is true for the obligation to read and hear, and therefore, as well as her ability to read the Megillah publicly. This position is not the custom in the overwhelming majority of Orthodox congregations; however, Berkovits brings the array of well-known sources and argues for maintaining the original halakha. He also demonstrates that some early authorities compared Kiddush to Megillah reading. While some tried to use this connection between the two to limit when women could recite Kiddush, Berkovits turns the argument around. He suggests that one follow the Shulhan Arukh, “Women may perform Kiddush on behalf of men because they are obligated to do it just as men” (O.H. 271:2). Berkovits goes on to suggest that families trade off: “there is no reason whatsoever why in our days husband and wife may not alternate from Shabbat to Shabbat in saying Kiddush. It would be our expression of respect for wife and mother” (142).

The essay at the end of the work, reprinted from the Milin Havivin journal (2014), is incredibly enlightening. Mohl compares Rabbi Berkovits’ philosophical understanding of God’s self-limitation to the idea of tzimtzum popularized in the writings of Rabbi Yitzhak Luria and subsequent kabbalists. For the Kabbalists, tzimtzum creates space for what we experience as reality, whether physical or spiritual. For Berkovits, it comes to create the ability for human self-expression. “Rabbi Berkovits was unique in that he clearly utilized the mystical concept of tzimtzum within his rationalistic philosophy without delving into the mystical and cosmological meaning of the idea” (144). Seemingly, the author included this essay (which has no direct connection to Purim) to highlight Berkovits’ primary worldview. As in the story of Purim, God has to pull back, as it were, and hide the Divine self in order to give room for human expression. Purim is the story of redemption during “hester panim” or divine self-limitation. For Berkovits, this notion, similar to the idea of tzimtzum in kabbalah, is critical not only for the Purim story but for understanding the human relationship to God.

[Read Eliezer Berkovits’ many contributions to TRADITION in our archive.]

Overall, this is a noteworthy and user-friendly volume. The inclusion of the complete Maariv service makes it useful to take to synagogue on Purim eve. Mohl suggests that “through this commentary, I hope the reader will gain a greater appreciation of Rabbi Berkovits’ contributions.” The author has ably presented a wide range of Berkovits’ writings in easily consumed fragments which, if Mohl has succeeded, will encourage the reader to seek out the original sources.

Composite commentaries such as Faith Fulfilled are increasingly common today. The genre presents a difficulty for the editor. How does one create a commentary to a classic work from a swath of writings when the author of those originals did not write such a commentary? This anthology-style, picking and choosing from here and there, so popular in many recently published volumes, often does a disservice to the original material and its author. Often the method does not generate a coherent new commentary. Mohl escapes this problem in some ways, but in others he is less successful. The commentary to the Maariv service presents many snippets from Berkovits’ work on prayer. Although he did not write a siddur commentary per se, he did write “comments,” which Mohl successfully transferred from essay form to the commentary. When commenting on the prayer “Heal us, Lord, and we shall be healed, save us, and we shall be saved,” Mohl quotes Berkovits: “When he supplicates, ‘heal us, Eternal One, and we shall be healed, save us, and we shall be saved…,’ the individual Jew may be in perfect health” (37). Here the commentary is a natural outgrowth from the original essay. Nothing seems lost. Mohl presents Berkovits’ beautiful Kavvanah on this blessing. Even when culled from works not on prayer the comments fit. On the prayer against slanderers, Mohl presents a small slice of Berkovits’ larger discussion from Faith After the Holocaust. In this comment, Berkovits contextualizes what he calls a “not very laudable [prayer]” in light of antisemitism and corrects a Christian misinterpretation (42). The compatibility of the commentary to the prayer service in general and the Amida in particular works rather well. Prayer after prayer is accompanied by matching comments.

At other times, this project comes across as a bit stilted. A comment to the blessing, “For we have sinned” does not fit well. The comments are from a section on Faith After the Holocaust relating to theodicy and “Because we have sinned.” These are two entirely separate categories. The prayer book discusses how prayer should relate to personal failure. That people stumble and fall is not a debatable issue. In context, and even in this work, the essay relates to theological claims of why bad things happen to good people. The section is part of an extensive discussion of theodicy and is not related to the subject of this prayer.

This problem becomes exacerbated in the section on the Megillah itself. Unlike prayer, Berkovits did not write a systematic essay on this biblical text. The excerpts are often uneven and do not always match. On the verse which briefly mentions exile, the author presents a section from Faith After the Holocaust about the necessity of the Roman exile. Similarly, commenting to the verse that “And the king loved Esther above all women,” Mohl presents a discourse from Crisis and Faith about the significance of romantic love. This seems forced. It may have done more to advance engagement with Berkovits’ thought for Mohl to have written his own commentary, drawing on his expertise in Berkovits’ ideas and writings. Such a commentary would have given the work a more holistic feel.

Nevertheless, what Faith Fulfilled offers the reader is a comprehensive look at elements of a profound thinker and theologian. By presenting various pieces in a range of ways – essay, commentary, and full excerpt – one walks away with a taste of the depth and breadth of Berkovits in full. The author presents a helpful companion for Purim night and a worthwhile and often challenging offering of thoughts and comments to enrich the Purim season.

Rabbi Tuvia Berman is the Director of Institutional Advancement and a Ram at Yeshivat Eretz HaTzvi.