Telltale Textiles from Biblical Times

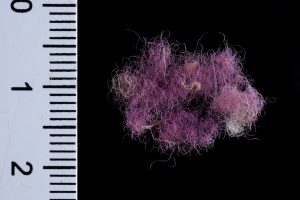

In Ancient Rome, when the Emperor’s wife was about to give birth, she was brought into a room decorated exclusively in the color purple. The future leader was literally “born into the purple,” a phrase which has come to mean born into nobility, destined for greatness. The recent archeological find in Timna of several scraps of purple-dyed fabrics dating from c. 1000 BCE, approximately during the reign of King David, analyzed by Dr. Naama Sukenik of the Israel Antiquities Authority, underscores how purple textiles were already a valuable commodity in the Southern Levant far earlier than the Roman period. Purple dyed cloth (argamanu in Akkadian) is the argaman mentioned throughout the Bible, most prominently along with sky-blue tekhelet and tola’at shani, in the list of luxurious materials used in the Mishkan and in the garments of the priests who served there. Tekhelet is also, of course, the blue thread which the Bible commands each Jew to affix to the tzitzit on the corner of his garment.

Wadi Murabba’at textile (c. 2nd century CE) dyed with blue from murex snails (Photo: Clara Amit, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Both argaman and tekhelet are derived from the secretion of a small gland in the sea-snails of the murex family found in the Mediterranean Sea. Different species of murex naturally yield various shades of purple. To produce the pure sky-blue of tekhelet, another step is required – exposure to sunlight at a specific stage in the dyeing process. This phenomenon was discovered only forty years ago though it was evidently well-understood by the ancient dyers. Once the dyeing is complete and the color set, it will not change or fade. Maimonides’ description of the dye: “steadfast in its beauty and will never alter” (Hilkhot Tzitzit 2:1), is certainly attested to by the rich hue seen in these newly rediscovered, 3000 year-old samples, as well as in the blue threads of tekhelet discovered in the wadi Murabba’at caves (also analyzed by Sukenik), dating to the first century CE.

Tufts of wool dyed with murex trunculus glands under identical conditions. The dye vat of the blue tuft was exposed to sunlight, the vat of the purple tuft was not (Photo: Assaf Stein, Ptil Tekhelet)

In the ancient world, where most fabrics were dull and drab, these deep purple and blue dyes instantly cast their spell on all who came in contact with them, sparking what Pliny the Elder describes as a “mad lust for purple.” In Greek the term “purple” (πορφύρα / porphyra) referred to all the dyes derived from sea-snails which ranged in color from reddish-burgundy all the way to blue-violet. To add to the confusion, the same word was also sometimes used to indicate the snails themselves and even the dyers as well as the merchants who dealt with them. The process involved in the production of these textiles, from catching the large quantities of snails required, to extracting the precious drops of dye from the gland, to the exacting method of dyeing the fabric, was intricate and painstaking. This meant that the price these dazzling colors could command was often equally as dazzling. At one point, records show, tekhelet was worth twenty times its weight in gold. These fabrics quickly became a status symbol, reserved for the upper class, and laws were eventually passed prohibiting the use of the dyes by anyone other than the nobility. Imperial regulation reached its climax under the Codex Justinianus (6th century CE), which warns that one who produces or sells the snail-dyed fabrics without permission “will incur the risk of losing his property and his life!” While in Rome the blue and purple clothes became a way to exclude the commoner from elite society, the Torah calls upon the entire community to step up and join the religious aristocracy. The Kohen Gadol in the Beit HaMikdash dressed in a robe of pure, striking blue, the lay priest in an all blue sash, and each individual is told to attach one thread of tekhelet to the corners of his own garment, so that the Jewish people literally become “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6). The tzitzit, Professor Jacob Milgrom suggests, illustrate “the epitome of the democratic thrust within Judaism which equalizes not by leveling but by elevating: all of Israel is enjoined to become a nation of priests.”

The recent Timna find may represent another interesting distinction between the aesthetic preferences of the ancient Israelites and the surrounding cultures. Purple ranked highest on the list of luxury fabrics to the world at large. Timna (about 30 km. north of Eilat) was actually a province of Edom in the first millennium BCE, and not Israelite territory, and therefore one might expect their nobility to wear argaman. This is attested to in the description of the booty taken from Edom’s neighbors (or perhaps antecessors) in Judges 8:26, “…and the purple robes worn by the Kings of Midian.” In Jewish tradition and culture however, tekhelet is considered the more valued color. It appears first in the Torah’s list of precious fabrics suggesting its higher estimation (cf. the order of the precious metals recorded) and many of the most prominent religious materials, the me’il, the band holding the golden tzitz on the high priest’s forehead, the tzitzit, and the covering of the Holy Ark are made exclusively out of pure tekhelet. One can wonder if that preference is only a matter of taste, or if there might be a deeper idea at play.

In various cultures, purple is associated with blood – at times symbolizing the blood of childbirth and fertility, but more often, violence and death. In the ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern world, the association of purple and blood came to represent the victorious hero in battle. Isaiah (63:1-3) graphically depicts God triumphantly vanquishing His enemy like a winemaker crushing grapes underfoot: “Who is this coming from Edom in wine-colored garments from Bozrah – Who is this, majestic in attire pressing forward in His great might? … I trod them down in My anger, trampled them in My rage; Their life-blood bespattered My garments, and all My clothing was stained.” A thousand years later, the most prestigious of all Roman attire was the Toga Picta, completely purple and hemmed in gold, worn only by the victorious general returning from war. The connection of purple and blood is noted by Nahmanides (Exodus 31:10) as well, who explains that when the Mishkan was dismantled for traveling, the sacrificial altar was covered specifically with a cloth made of argaman (as opposed to the golden incense altar and the ark, which were draped in tekhelet) to allude to the sacrificial blood which was sprinkled upon it. Though purple was prized above all other colors by the ancient cultures surrounding Israel, the Jews esteemed the sky-blue tekhelet as the most cherished and holiest of all colored fabrics. Purple, though beautiful, is raw and earthy, but tekhelet, like the deep, fathomless ocean, and the vast, soaring sky, reaches out to infinity. “Why is tekhelet singled out from all the colors?” Rabbi Meir asks, “Because tekhelet is similar to the sea, and the sea is similar to the sky, and the sky is similar to the Holy Throne” (Sota 17a). Along the same lines, though from an entirely different milieu, the great Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky, who had the fascinating neurological condition known as synesthesia, where he experienced color not only visually but also audially, writes, “The deeper the blue, the more it beckons man into the infinite, arousing a longing for purity and the supersensuous. It is the color of the heavens just as we imagine it.” Gazing upon the color of tekhelet – as the Torah enjoins us to do with the tzitzit strings, “and you shall look at it” (Numbers15:39) – inspires us to lofty, transcendent contemplation.

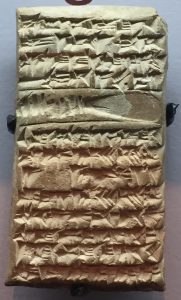

Late Assyrian clay tablet, Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem (BLMJ 65j). The document is “sealed” with a knotted cord and fingernail impression.

According to the Timna study, one of the samples (no. 017) “seems to be an element of a fringe or tassel.” The idea that such extravagant cords hung from the hems of garments suggests that they may have been more than just a flashy fashion statement. Indeed, in some cases, archeological evidence has shown that these fringes served an essential and highly significant social function. In ancient times, intricate, knotted tassels would be pressed into the soft clay of a cuneiform “document” as a means of “signing” and authenticating the veracity of the contents. Each “signatory” had his own unique arrangement of knots on his tassel, so that by looking at the impression in the clay, one could verify the author. The tassel hanging from one’s hem thus became a tangible symbol of that person’s identity. This may shed light on the episode in Genesis (38:18) where Yehuda hands Tamar his “seal and cord” as collateral. The seal, which served as a way to authorize, was often made of precious material such as the blue lapis lazuli stone. Likewise, the cord or tassel could have served a similar function and would therefore also be fashioned from expensive threads. Assyriologist Ephraim Speiser has proposed that the custom, still practiced today, of touching ones tzitzit to the scroll when being called up to the Torah may have originated as “a dramatic reaffirmation of the participant’s commitment to the Torah,” impressing his signature, so to speak, to the words written on the parchment.

Archeological finds of dyed textiles in general are rare, and those from Timna are now the oldest known murex-dyed fabrics in the region, surviving the millenia presumably because of the arid climate which allowed for their preservation. In Talmudic times it was virtually impossible to distinguish between authentic snail-dyed tekhelet and the fraudulent plant derived indigo known as kala ilan. This prompted the Rabbis to level severe curses upon those unscrupulous dealers who would peddle in cheap imitations. Today, however, modern chemical analysis, like that done by Sukenik and her colleagues, can determine incontrovertibly that fabrics were dyed with murex by detecting traces of molecules containing bromine, which are never found in plant-based dyes, but exist in all murex-dyed fabrics. Sometimes, through examination of the relative proportions of the various molecules, even the exact species of murex can now be determined. The Timna find may be the oldest in the region but is not the oldest murex dyed fabrics ever found. That distinction belongs (so far) to fragments unearthed at the ancient kingdom of Qatna, which is about ten miles north of Homs in modern day Syria. Those fabrics date to the mid-second millennium BCE, but there is some evidence that murex-snail dyeing was practiced as early as 1750 BCE by the Minoans on the island of Crete.

Each newly discovered scrap of fabric opens a small but often significant window into the lives of the people who lived in Eretz Yisrael in ancient times. The fascinating story of tekhelet and argaman, from their central role in the world’s economy, to their complete disappearance in the 6th century CE, and the eventual rediscovery of their marine source and the dyeing process in modern times, is one which is still unraveling.

Baruch Sterman is co-founder and CEO of Ptil Tekhelet. He and Judy Taubes Sterman are co-authors of The Rarest Blue: The Remarkable Story of an Ancient Color Lost to History and Rediscovered, winner of the Jewish Journal Book Prize.