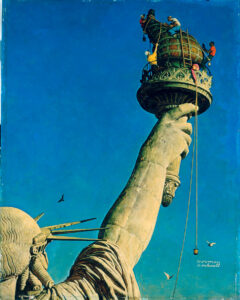

The BEST: Working on the Statue of Liberty

Summary: “Working on the Statue of Liberty” is a 1946 oil painting by the renowned American artist Norman Rockwell. Commissioned for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post for the first July issue following the end of World War II, the painting depicts five workers giving the amber glass of Lady Liberty’s torch its annual summer cleaning (which ceased in 1986, when the flame was replaced by a gold replica). Steven Spielberg, who had acquired the painting, donated it to the White House in 1994. The painting was displayed in the Oval Office during the administrations of Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama, and remains part of the White House’s art collection.

Why this is The BEST? The Statue of Liberty is often imagined from the perspective of hopeful immigrants approaching Ellis Island: the strong face and steady gaze of America’s most iconic symbol, a long robe draped across her figure, a tablet cradled in her left arm, and a torch raised in her right hand, lifting her “lamp beside the golden door” (in Emma Lazarus’ phrasing). Norman Rockwell depicts a different, rare, and meaningful vantage point. In Rockwell’s painting, we see Lady Liberty from behind, with our feet already firmly planted on American soil.

The Statue of Liberty—for all the freedom and “world-wide welcome” that she symbolizes at the entrance of New York Harbor—is not the central figure in this painting. The painting only captures a portion of Lady Liberty’s figure: the back of her head, her raised right arm, and her famous torch. The coils in her hair are unruffled by the wind, and the creases in her robe are permanently stiff. Scanning the canvas, the viewers look for movement. Our focus is lifted even higher than her figure, drawn to the action at the top right of the canvas where the torch’s flame is pointed heavenwards. It isn’t the brightness of the flame that attracts our attention, but the flurry of collaborative activity occurring at the base of the torch.

Five workers, composing a diverse team, clean the glass of the flame. They each engage in their own productive task, depending on the others, and even on those who are not in the painting: the buckets and ropes pulled in and out of sight allude to more workers on the ground helping those above. A note accompanying the painting read: “Freedom takes a lot of work,” and the workers are critical to that effort. It is precisely the workers’ status as members of a group that enable them to perform their civic duty in the upkeep of the symbols valued by the nation. While they may come from different backgrounds, it is their current teamwork—the participation of a multitude dedicated to the same goal—that accomplishes a task. After all, as the painting depicts, Lady Liberty is notably manmade; a close look at Rockwell’s brushstrokes along her arm reveals the indentations along the individualized riveted sheets of copper that unite in holding her structure together.

“The BEST” is a work that is in constant progress. The Statue of Liberty has changed from the time she was assembled on America’s shores—her copper form has oxidized, her flame has been exchanged, but her message of freedom remains the same. When Rockwell paints this image after World War II, he depicts America’s hardest workers teaming up so that Lady Liberty’s beacon of light can shine brightly again. The Statue of Liberty has stood throughout the waves of immigration, receiving newcomers with all the innovation they bring. Similarly, our Jewish legacy includes a Torah that never changes, but an Oral Tradition that allows for debate and progress over generations. Notably, the medium that Norman Rockwell chose to portray this image simultaneously exemplifies its message: an oil painting is rarely ever finished. Oil paint can take years to fully dry and can always be revived; with the application of more oil, the paint becomes malleable under the brush once again, allowing the artist to continue the work that needs to be done.

Chaya Sara Oppenheim recently graduated from Barnard College where she studied English and history.