The Complexity of Hesder Revisited

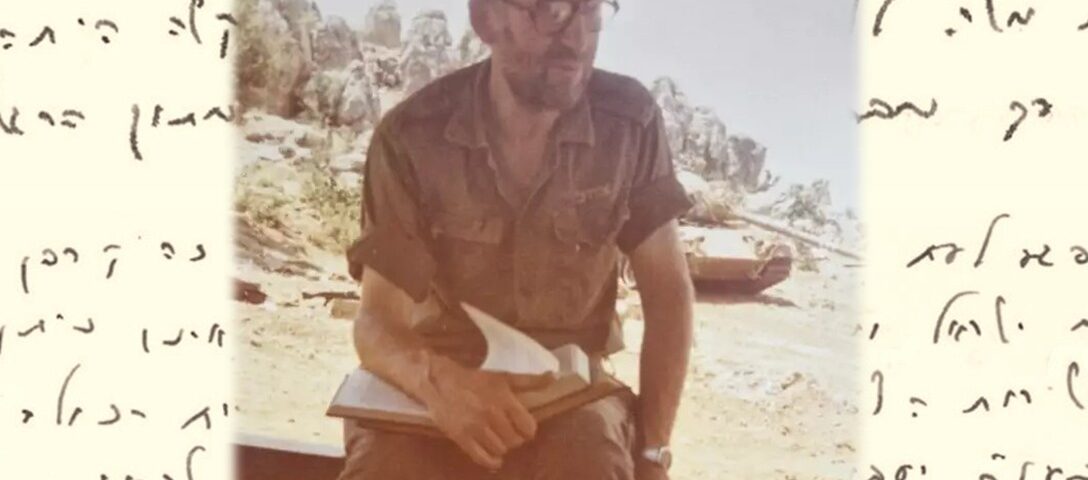

R. Aharon Lichtenstein, in uniform, delivering a shiur to Hesderniks in Lebanon, Summer 1982 (courtesy: Elitzur Emmanuel).

In the ten years since the passing of my father, my teacher and master, Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l, we have faced difficult and challenging times, foremost among them the massacre on Simchat Torah 2023 and the ensuing war. My father, now gone for a decade and receding into the mist of the past, has not experienced these ordeals together with us. Yet, although his voice has been silenced, the influence of his consistent Torah-based ethical values has not ceased.

I wish to present here a small selection of his vast worldview related to an urgent issue in Israel’s public discourse—his clear position obligating all yeshiva students to enlist in the Israel Defense Forces and share the burden of combat. I will first present his position on the damage done to Torah by those who remain exclusively in the beit midrash at such an hour, and then propose a course of action, based on his teachings, for expanding the circle of yeshiva students enlisting. All this is offered with the hope that his words, spoken from a pure heart, will enter the hearts of my readers.

In 1981, in the pages of TRADITION (19:3), my father published his essay “The Ideology of Hesder” (published the following year in Hebrew in Yeshivat Har Etzion’s journal, Alon Shevut #100). True to form, he addressed the topic from multiple angles. He presented military service as an urgent necessity, as a clear and present mitzvah; laid out the justification for shortened military service for yeshiva students; extolled the contribution of Hesder’s combination of study and service to the nation and the IDF; pointed out the difficulties inherent in the Hesder track; and offered solutions.

His primary halakhic argument presented Hesder as a clear fulfillment of “Torah combined with acts of lovingkindness.” As one who consistently followed the ways of Beit Hillel, giving precedence to his opponents’ arguments before his own, he fairly and thoroughly presented the views of those who exempt yeshiva students from military service. He engaged with their arguments and sources, but ultimately concluded that they do not provide a sufficient basis for a sweeping and definitive exemption for Torah scholars.

The essay was published over forty years ago, closer in time to the founding of the Hesder movement in 1953 than it is to our own day. It expresses an original position that at that time was not accepted even among other heads of Hesder yeshivot. Anyone reading the essay feels its polemical tone—one that, as often happens, engages most ardently with those closest to one’s own position. My father chiefly confronted the track known as “Hesder Merkaz” (centered on Yeshivat Merkaz HaRav). He argued that the key difference between the varieties of Hesder experience was whether they viewed military service merely as a necessary preparation for war, should it arise (as all in Israel reasonably suspected it would; indeed, the First Lebanon War broke out less than a year after the essay was published), or whether they also saw bearing the burden of ongoing national security as an inherent obligation for Torah scholars.

Here, I will highlight a paradox in the positions of both sides. Merkaz HaRav, which champions Rav Kook’s Torah—a Zionism of action that sees the State of Israel as the realization of prophetic vision—nevertheless supports shorter military service for yeshiva students in favor of increased time on the benches of the beit midrash. Meanwhile, my father, whose Zionism drew from entirely different sources, called for longer military service for students of Torah. This paradoxical reversal is rooted in a deep difference in worldview regarding the sacred, the secular, and the nature of the State of Israel. With the “image of father appearing before us in the window” (cf. Sota 36b), I will attempt to offer an explanation and reexamination of the issue through the lens of our present experience of a year and a half of continuous warfare.

Hesder as an Ideal

When my father arrived in Israel in the summer of 1971 there were few Hesder yeshivot. Many of the roshei yeshiva and ramim of that time had grown up in the Haredi system. How did they view their Hesder students? I heard from Rabbi Haim Sabato that his teacher at Yeshivat HaKotel, Rabbi Yeshayahu Hadari zt”l, described Hesder’s goal as “to bring Torah to the boys of Bnei Akiva.” The assumption behind that statement was that Hesder represents a compromise or concession—a yeshiva for Religious Zionists (who probably couldn’t handle a “real” yeshiva), where they could learn a bit of Torah alongside serving in the army.

Such a yeshiva was seen as a realization of the Mizrachi movement’s vision, emphasizing “Torah and…” In other words, much of the Hesder leadership viewed its very own institutions as a bedi’avad (less than ideal) option, meant for those who had already chosen the path of Religious Zionism and its compromises. For a boy whose soul thirsted for Torah and who aspired to grow in learning their recommendation was to study full-time in a “proper” yeshiva, nicknamed the “Holy Yeshivot,” and take the exemption from army service.

My father represented a completely different orientation: Hesder as an ideal (lekhathila). Rabbi Re’em HaCohen told me that as he was finishing Netiv Meir high school and was deliberating about his next step, he consulted with my father. He asked him about the choice between a “Holy” and a Hesder yeshiva. Father surprised him with his answer: He said that someone unable to handle the dual challenge of serious Torah study along with the military should opt for a yeshiva without army service. But one who is strong and capable of both deep Torah study and army service should choose Hesder—which he saw as the more challenging but preferred path.

Indeed, anyone who learned at Yeshivat Har Etzion knows that my father viewed the yeshiva as a kind of Volozhin-like ideal in terms of his expectations of us, his students. Those expectations were high—in terms of diligence, academic level, and aspirations. He envisioned a yeshiva where the sound of Torah would not cease for even a moment. True, there were extended periods when students would leave the beit midrash, but this did not diminish the vision that here, the banner of Torah would be borne high—equal to or surpassing other yeshivot.

This worldview is expressed in the main argument presented in “The Ideology of Hesder,” regarding Torah combined with hesed (acts of kindness). My teacher and master, Rabbi Yehuda Amital zt”l, shared this worldview, and that is why he drafted my father to stand alongside him at the head of Yeshivat Har Etzion, so that the institution would be led by a Torah role model of the highest caliber. Despite their differences, they found common ground in many areas, among them a shared vision regarding the mission of the Hesder yeshivot. The difference between them, in form not in essence, is demonstrated in R. Amital’s well-known expression of his worldview through a short Hasidic story, while my father encapsulated his philosophy through a complex, twenty-page scholarly essay. Nonetheless, the ideas are one and the same. R. Amital would often relate the tale of Rav Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the Ba’al HaTanya, who lived for a time in a modest dwelling with his son and infant grandson. The house had three rooms: The Ba’al HaTanya sat and learned in the innermost room; in the middle room sat his son, later known as the Mitteler Rebbe, also learning; and in the outer room, the infant lay in his cradle. During his study, the Ba’al HaTanya heard the infant crying, and, as he passed through the middle room, noticed that his son was so engrossed that he did not hear the baby. After comforting the child, he rebuked his son: “If one learns Torah and does not hear the cry of a child, there is a flaw in his learning.”

R. Amital’s message about personal responsibility is clear. My father’s article expresses a similar worldview: One who studies Torah without national responsibility, one who learns without combining study with acts of kindness, one who walls himself inside the four cubits of the beit midrash and does not hear the needs of the Jewish People—his Torah is deficient. A moral obligation lies on every person, and certainly every Torah scholar, to shoulder responsibility for society. Since in the State of Israel the existential and security threat stands at the forefront of our national challenges, yeshiva students must take part in addressing it.

How far removed these words are from the militarism and adulation of the army so typical today in broad circles of the Religious Zionist and Haredi Leumi public. In his famous address on Yom HaAtzmaut 1967 (shortly before the outbreak of the Six Day War), Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook zt”l justified IDF military parades by saying: “Everything connected to the army—every weapon of all kind, whether made by us or by Gentiles, everything associated with the day of Israel’s national rebirth—it is all holy.” My father was extremely wary of ascribing “holiness” to weapons of war. In the summer of 1979 I was in Boston visiting with my grandfather, my master and teacher, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zt”l. In a letter sent during that trip, my father shared his feelings on accompanying my older brother, R. Mosheh, to his enlistment for combat service in the IDF:

A few minutes ago I brought Mosheh to the Jerusalem recruitment office. The parting was difficult for us, not only personally, but also out of the feeling and knowledge that his enlistment would temporarily hinder his growth in Torah. But this is a sacrifice demanded by the situation of the People of Israel and the State of Israel, a situation where, under our current conditions, military service can be seen as a duty, a privilege, and a responsibility all at once. We hope, with God’s help, that all will pass safely, and that we will see him soon again with us and within the walls of the study hall, in peace and tranquility.

“One thing I ask of the Lord, that I may dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life” (Psalms 27:4) is the motto of authentic Torah students; it certainly encapsulates my father’s stance. And nonetheless, one who wishes to be a full member of the beit midrash must know the secret of going out when circumstances demand, as a duty, privilege, and responsibility. And even so, the going out is a sacrifice made with pain, not out of glorifying militarism. This was his outlook: Not the glorification of militarism, but one who sees military service as a painful obligation, alongside Torah study as an aspiration and a vision.

[R. Mosheh Lichtenstein discussed his own take on “The Ideology of Hesder” on the Tradition Podcast (September 2024).]

Ongoing Security Duty

When my father wrote “The Ideology of Hesder,” the accepted view among the Hesder yeshivot was that the main purpose of the soldiers’ service was to prepare them for wartime. The Hesder track was perceived as a framework that trains soldiers whose real contribution will be to stand at the ready as reservists in the case of war. But my father emphasized a different aspect—namely, the ongoing need to bear the burden of security during routine times.

He expressed amazement that those (in the orbit of Merkaz HaRav) who view the State of Israel as “the beginning of the flowering of our redemption” are precisely those who limit their military service to short periods, arguing that it is sufficient to train for wartime and that the regular army will handle the day-to-day security. He asked, If the State is truly the “beginning of redemption,” why shouldn’t Torah students take a more active role in the ongoing work of maintaining the security of its citizens?

He recognized that there is a valid claim for those who argue Torah study outweighs military service, and therefore, one may limit military service to a minimum necessary for security needs. But he rejected the claim that the Torah student’s responsibility ends with being trained as a fighter and that there is no obligation to share the ongoing burden of guarding the nation and its citizens. Therefore, in his view, not only did Torah students have an obligation to enlist in the army, but even more, they had an obligation to bear part of the permanent, continuous, grinding security burden; not merely to “prepare for emergency” while others carry the day-to-day burden.

In doing so, he painted a much more demanding picture of the ideal Torah student. Not only should he be great in Torah and capable of potentially becoming a halakhic authority, but he should also be someone willing to sacrifice and share in the needs of the public even at the cost of his own personal Torah growth. That is, Torah study is of supreme importance, but it must be joined with responsibility for society even when it comes at a steep personal price.

A Time to Expand the Model

My father notes in the article that, in light of the changing security needs, it is appropriate to periodically examine the Hesder track. We have reached such a point. The current situation, with its prolonged and persistent threat to the State of Israel, invites a renewed examination of my father’s teachings. It seems that his arguments, which were innovative four decades ago, invite even broader conclusions today. He justified the shortening of service in the Hesder track (compared to those who do “full army”) for two reasons. First, to allow for significant Torah study; second, because of the presumption that the main security burden would be carried by regular army soldiers. But the situation has changed. The line between wartime and routine-time has blurred. Routine times are filled with countless security incidents, attacks, bombings, border infiltrations, and more. Soldiers today are not merely training for a future war; they are engaged daily in the war for life.

This is the reality that my father referred to. If once shortened service was justified by the existence of “regular security,” today that justification has weakened. The burden of ongoing combat is constant and continuous, and the obligation to share it is even greater. Therefore, it seems that the time has come to rethink the model of Hesder service. Without abandoning for a moment the foundation that Torah study is the main calling of a Torah student, we must seriously consider lengthening the period of military service in the Hesder framework, so that Torah students will bear a fuller share of the national burden. In this way, we will be faithful to the great principles my father established: To integrate Torah study with acts of kindness, and to join the beit midrash with the duty toward the nation.

On the other hand, the soul-searching demanded at this moment also pulls in the opposite direction—toward strengthening the cultivation of Torah scholars from within the Hesder yeshiva community. After all, the core of the debate with the Haredi public is, at root, the question of what Torah truly is. The people of Israel need Torah scholars who embody a a living Torah yoked to national responsibility. We must not abandon the field of spiritual leadership, and leadership development, to those yeshivot which reject army service combined with Torah study. Thus, this moment of reflection draws us in two opposing directions: on the one hand, attentiveness to very serious security needs and extending military service; on the other, encouraging students of the Hesder yeshivot to aspire to become true Torah scholars. Who, more than my father, taught us how to live with such complexity?

In order to understand how a person could imagine he was teaching in Volozhin while willingly sending his students off to the army as an ideal (the IDF, mind you, not the Czar’s army!), we must bear in mind my father’s ability to be entirely devoted to God while simultaneously engaging in secular fields. How could someone who was wholly sanctified invest great effort, and even excel, in the study of English literature? Like Maimonides, my father was enraptured by the love of Torah from his youth, and possessed the unique ability to be entirely devoted to Torah while also engaging with other matters. In contrast to R. Tzvi Yehuda’s assertion that “everything is holy,” my father’s world had room also for the secular without the need to make such a claim. If we try to understand how a person can be wholly sanctified and at the same time make space for the secular, we must arrive at a central character trait of my late father, one that he fully embodied.

Maimonides describes the proper way for a person to conduct his life: by adopting the middle path, equidistant from either extreme (see Hilkhot De’ot, ch. 1). He describes the Hasid (pious one) as someone who goes beyond the letter of the law, slightly tilting away from the middle in one direction or the other. We inscribed on my father’s gravestone: “Gaon and Hasid” (Genius and Pious). While Maimonides’ Hasid goes to one extreme and remains there, my father would go toward both extremes and would return, carrying the virtues of both extremes with him, to live with both together at the center. My father viewed the Hesder model as fulfilling this ideal of simultaneously grasping both ends. At its core resides the value of entire dedication to Torah (Volozhin-like), while also holding fast to the value of national and communal responsibility through military service. He held onto both values and lived them simultaneously. He built Yeshivat Har Etzion in the image of this vision, simultaneously dedicated to Torah and to national responsibility. He presented us with a model that this life is possible and demanded of us, in the strongest terms, that we aspire to be Hasidim like him.

“For if you remain silent at this time”

Let us amplify my father’s voice in these days of ongoing war, in which active combat and “routine” security operations blur together, and reservists bear repeated cycles of duty under the heavy burden of defense. This exacerbates the existential need to expand the IDF’s fighting forces. In this reality, we will moderate the polemical tone that my father once used in criticizing the “Hesder Merkaz” track. Despite their shortened active service, we express profound appreciation for the yeshiva students who fight, who undergo this training track, and who are full partners in the ongoing battles, serving many years in the reserves, and making a highly significant contribution to the IDF’s forces.

Our focus now shifts to the circle of yeshiva students who do not serve in the IDF. There are many reasons for this, some of which may have been justified in the past, foremost among them the Haredi community’s lack of identification with the Zionist enterprise. I understand their difficulty in seeing R. Tzvi Yehuda’s proclamation of the army as “holy” as a call that would motivate them to act. However, it is precisely from my father’s locating the obligation to serve not on Zionist ideology but on the ethic of joining Torah with acts of kindness that we appeal to the Haredi public to join the fighting ranks of the IDF.

In his name, we say to this community: You are part of the inhabitants of the State of Israel; our enemies are not fighting against Zionist ideology alone but seek to murder us all, including you. Do not remain silent at this time by staying inside the study hall and turning a blind eye to the serious manpower shortage, to the obligation of saving Jewish lives. Do not ignore the needs of the People of Israel, fighting on multiple fronts against enemies who seek our destruction. Please hear my father’s clear and unwavering voice calling for a full obligation upon yeshiva students to enlist in the IDF. One who studies Torah but does not go out to fight at this time, his Torah is deficient.

In his name, we say to this community: You are part of the inhabitants of the State of Israel; our enemies are not fighting against Zionist ideology alone but seek to murder us all, including you. Do not remain silent at this time by staying inside the study hall and turning a blind eye to the serious manpower shortage, to the obligation of saving Jewish lives. Do not ignore the needs of the People of Israel, fighting on multiple fronts against enemies who seek our destruction. Please hear my father’s clear and unwavering voice calling for a full obligation upon yeshiva students to enlist in the IDF. One who studies Torah but does not go out to fight at this time, his Torah is deficient.

Moreover, take note, in his approach to military service, my father paved ways that would enable even you to find paths to enlist—to hold onto both the Torah and national responsibility. This is the call of the hour, a matter of national pikuah nefesh. By enlisting in the army, you will also become partners in the redemption of the Torah—a Torah of life. This is the true Torah, one that does not separate itself from life; a Torah that sanctifies life, that heeds the cries of infants, soldiers, bereaved families, and a nation that needs protection.

Mayer Lichtenstein, Rav of Beit Knesset Ohel Menachem in Beit Shemesh, is a Ram at Yeshivat Orot Shaul in Tel Aviv. This essay (translated by Jeffrey Saks) is excerpted from his newly released Musar Avi: Shiurim Be’ikvei Torat Avi Mori HaRav Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l.