The Early Days of Bais Yaakov: A Peek Inside the Classroom

The Early Days of Bais Yaakov: A Peek Inside the Classroom

Channa Lockshin Bob

In recent weeks, as schools and universities around the world have shifted to online teaching, a conversation has begun about the nature of education. Is the primary mission of schools to transmit content, which can be achieved online, or is their central purpose to provide social stimulation, experiences, and a sense of community, none of which can be replaced by a Zoom session?

This fundamental question can also be applied to the historical study of education. When studying a school or educational movement, how much focus should be on the educational content, and how much on the community and experiences created by the school system?

In Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition (Littman Library, 2019), Naomi Seidman provides an engrossing and thoughtful treatment of the early years of Bais Yaakov. Seidman’s research is based upon a variety of primary sources, including diaries of Schenirer that have never before been published in English. However, most of the primary sources – memoirs, diaries, and the Bais Yaakov Journal – tell us much more about the experiential and communal aspects of Bais Yaakov education than about the content of the Bais Yaakov education in the early years.

[Read a review of Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement in TRADITION’s Winter 2019 issue.]

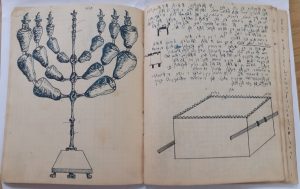

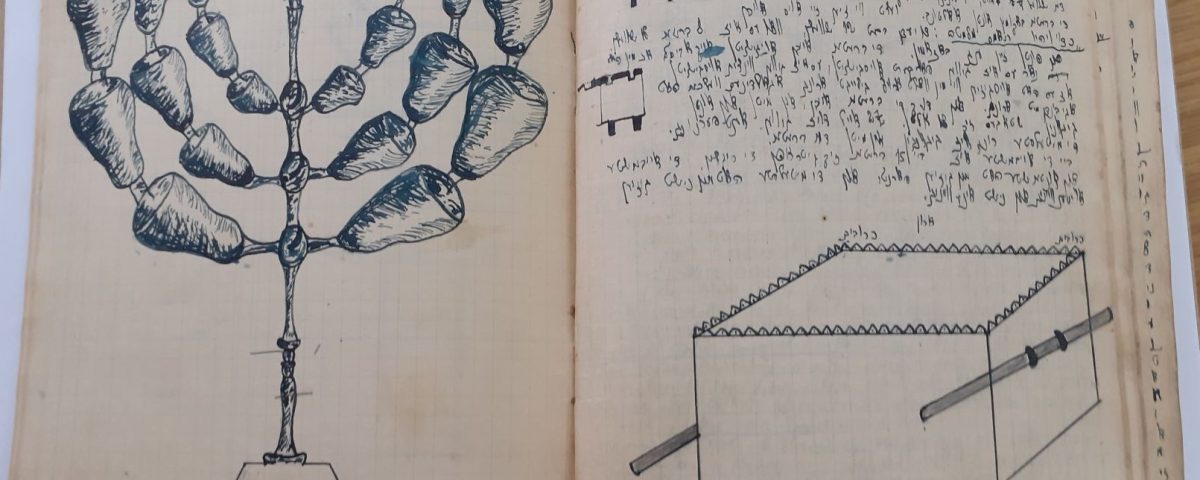

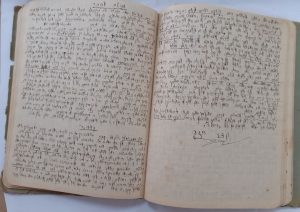

A collection of notebooks at the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, on the Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, offers a fascinating opportunity for researchers studying the Bais Yaakov schools to get a detailed and vivid picture of the educational experience inside the classroom. (It is unfortunate that this resource was not mined and analyzed in Seidman’s otherwise excellent book.) The collection includes forty notebooks with class notes from the Bais Yaakov teachers’ seminary in the mid-1930s. The teachers’ seminary in Krakow, which Seidman describes as the “crown jewel” of the system, attracted older teenage girls who wanted to become teachers at Bais Yaakov schools. Most of the notebooks belong to one student from the north-eastern Polish town of Tykocin, Gitl Lenczewski. Gitl filled the pages of her notebooks with small, cramped, handwriting, taking notes mostly in Yiddish with a sprinkling of Hebrew and Polish. The notes are so detailed that they transport the reader into Gitl’s classroom.

According to Sefer Tiktin, the Yizkor book for the Jewish community of Tykocin published in 1959, many young women from the town became teachers in Bais Yaakov schools. Gitl, one of eight children of an impoverished melamed, may have been one of the many young women who entered the teachers’ seminary partly in hope of finding a means of supporting herself. Unlike the majority of Bais Yaakov teachers and students, Gitl managed to get out of Poland before the Holocaust; at the time of the Yizkor book’s publication, she was married and living in Jerusalem.Gitl’s choice to bring the forty notebooks along when she left Poland is a testament to how significant her Bais Yaakov education was to her, and also a stroke of good luck for researchers today. The National Library of Israel and the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People purchased these notebooks in 2016, perhaps the only such collection in public hands today, as part of our mission to preserve and continually expand the world’s largest Judaica collection, granting public access to a wealth of different types of materials that can deepen our understanding of Judaism and Jewish life.

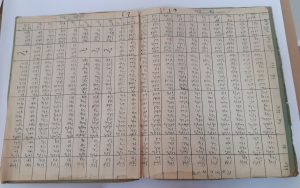

While other documents have already provided a basic sketch of the topics studied at the Bais Yaakov Seminary, the notebooks show the distribution of topics in much greater detail. The bulk of Gitl’s curriculum is devoted to Bible and Jewish History. Bible study involves going through nearly every book in the Tanakh, chapter by chapter and verse by verse, and analyzing it. Jewish history class offers a survey from ancient to contemporary times that looks more like a graduate level university Jewish history course than the training required to teach in an elementary or middle school that meets for a few hours in the afternoons. It is unlikely that Gitl or her classmates would end up teaching fifth graders about Eldad Hadani or Hasdai Ibn Shaprut, but they nonetheless learned about them, and many other obscure topics as well. The Jewish history curriculum is also surprising in the range of controversial ideas the students were exposed to, including the Maimonidean Controversy, the Haskala, and even a passage about Spinoza.Another prominent topic covered in the notebooks is prayer, with many units that work through and discuss the texts of daily and holiday prayers. While other materials about Bais Yaakov education tell us that students studied Hebrew grammar and pedagogy, it appears from these notebooks, assuming the collection is fairly complete, that these topics were briefly touched upon but not explored at length. The notebooks do contain plays, poems, and songs, which is consistent with what we already know about Bais Yaakov’s use of those creative media.

Notes from a Bible class, finishing the Book of Ruth and beginning the Book of Esther [click image to enlarge]

Gitl often notes the names of the teacher who taught the particular class session, and sometimes names of guest lecturers, such as one who taught a lesson about the geography of the Land of Israel. In one notebook she has a collection of torahs – short teachings – that include some by Frau Schenirer herself. Since the dates on the notebooks are mostly after the untimely death of Sarah Schenirer in 1935, it is likely that these were teachings passed on in her name.

Seidman asserts that the Bais Yaakov teachers’ seminary offered women the highest attainable Jewish education in a traditional setting. The notebooks demonstrate the truth of this statement.

The notebooks also raise some questions about what we think we already know about Bais Yaakov. For instance, in one notebook Gitl’s dates the material as the “fourth year of learning” and elsewhere “fifth year of learning,” which is curious since other documents about the Bais Yaakov Seminary in Krakow state that it was a two-year program.

It is hoped that future scholars will do more to harvest scholarly insights from these largely unexamined primary sources. Further in-depth study of the notebooks should go beyond a basic sketch of their contents and provide a fuller picture of the tone and atmosphere in which the material was taught. Just to bring one passage as an example, at the bottom of a page about the Maimonidean Controversy, Gitl writes: “Maimonides died in Egypt and was brought to burial in Tiberias. It is said about him, ‘From Moses to Moses there was none like Moses.’ But those who oppose him would erase that and write: ‘Here lies Moses the excommunicated apostate!’ ”

Whether the last sentence is Gitl’s own aside, or a joke cracked by the teacher and dutifully copied over by the student, it gives a glimpse of unexpected irreverent humor in the Bais Yaakov classroom. Who knows what surprises may await the scholar who delves into the details of these notebooks?

Channa Lockshin Bob works in the Judaica Collection at the National Library of Israel and teaches Gemara at Midreshet Amudim.

[Published on March 29, 2020]