The Guide to the Perplexed: A New Translation

Moses Maimonides, The Guide to the Perplexed: A New Translation, translated and with a commentary by Lenn E. Goodman and Philip I. Lieberman (Stanford University Press), 704 pages

Moses Maimonides, The Guide to the Perplexed: A New Translation, translated and with a commentary by Lenn E. Goodman and Philip I. Lieberman (Stanford University Press), 704 pages

[Listen to Menachem Kellner discuss this book on the TRADITION Podcast.]

Anyone attempting a technical review of a work in translation must have expertise in the original language of the text under review. In the case of the newly released edition of Maimonides’ The Guide to the Perplexed: A New Translation, brought to us by Lenn E. Goodman and Philip I. Lieberman, such a review would best be undertaken by a skilled Arabist, who is expert in Greek, Hellenistic and Arabic philosophy, and who is a rabbinic scholar. I do not satisfy those criteria and in this essay I will explain why readers of TRADITION should purchase and study this new, sparkling translation of the Guide, and why it should take its place as the translation of choice for we perplexed English readers. While it deserves a discussion and review of its own, Goodman’s marvelous companion volume, A Guide to The Guide to the Perplexed: A Reader’s Companion to Maimonides’ Masterwork, will not be discussed here.

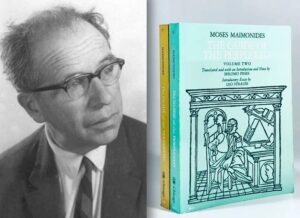

So, if not a “review,” this “profile” will focus on two elements of the work: the context of the translation, and its (Jewish) readability. Whenever I am about to teach Rambam, my wife cautions me: “Remember to tell the students that Rambam was also a rabbi!”—that is, an austere intellectualist who was also deeply religious. My wife’s comment goes to the heart of what I see as the greatest problem with what has until now been the “standard” English translation of the Guide, that of Hebrew University’s Shlomo Pines (d. 1990), published in 1963 by University of Chicago Press. Pines was assuredly a skilled Arabist, expert in Greek, Hellenistic and Arabic philosophy, but not a rabbinic scholar (nor a native speaker of English).

There are many ways of contextualizing Rambam. Traditionalist readers see him as functioning in a context that begins with Moses and continues to the present day. Readers such as Goodman and Lieberman see Rambam as functioning at the intersection of two vectors: one beginning with Moses, and the second beginning with Plato and even more with Aristotle. Pines sees Rambam as functioning primarily in the context of the non-Jewish intellectual movements which dominated his 12th century environment. This finds clear expression in Pine’s well-known (although perhaps less well-read) and long introduction to his translation on “The Philosophic Sources of The Guide of the Perplexed.” Pines devotes just 2 of his 78 page essay to “Jewish authors.” In doing this, he follows in the footsteps of some early Jewish philosophic readers of the Guide, including its original translator into Hebrew, Samuel ibn Tibbon, alongside ibn Falaquera, ibn Kaspi, and Narboni, all of whom read Rambam almost exclusively in a clearly philosophic context.

Pines’ understanding of Rabbi Maimonides comes out clearly in one word; he characterizes Rambam’s halakhic work (explicitly with reference to Mishneh Torah) as an “avocation” (cxvii)![1]

The almost purely philosophic context of Pines’ translation is further emphasized by that volume’s second introduction by Leo Strauss (d. 1973) who famously held that Rambam could not have been both a rabbi and a philosopher and was much more a student of Aristotle than of Moses. Strauss never met my wife. His 45-page introduction is called “How to Begin to Study The Guide of the Perplexed.” That essay is, to my mind, truly strange, and it is obvious that Goodman and Lieberman would not recommend using Strauss as a way of entering the study of the Guide. Neither would I.

Pines’ influence on the academic study of the Guide over the last half-century has been profound. Outside of Israel, and wherever readers turn to an English Guide, his is clearly the “standard” translation. It has certainly stimulated a renaissance of Maimonidean scholarship, much of it devoted to “Straussian” readings of Rambam, which search for his hidden messages. But even independent of Strauss, Rambam as presented in many important scholarly works in the past number of decades is a version of Pines’ 12th century not-particularly-Jewish philosopher writing in (Judeo)-Arabic. (A recent and extremely learned example would be Sarah Stroumsa, Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker.)

Pines opens his introduction by noting that Rambam mentions his Mishneh Torah repeatedly in the Guide (lvii). This is certainly true. There are also literally thousands of biblical and rabbinic references in the Guide, as indexed at the end of Michael Schwarz’s Hebrew translation (Tel Aviv University Press, 2002). Reading Pines’ translation with its scant notes, one gets no inkling of the significance of Rambam’s engagement with those classical Jewish texts and their role in the Guide. With that in mind, let us turn now to the new Goodman/Lieberman translation, focusing first on context. Reading this translation with its introductions and notes, we find ourselves studying a Jewish guide to a Jewish perplexed person written in a Jewish language. From the poem with which Rambam opens his Guide, through to the very last chapter, we find a book meant to lead the reader to a clearly intellectualist form of holiness (one open to all human beings, but here aimed directly at readers of Judeo-Arabic).

Further, the rich notes in the new translation make it clear that Rambam was in conversation with Jewish philosophers who preceded him, among them were Sa’adia, ibn Gabirol, Rabbenu Bahya, and Judah Halevi. Rambam rarely if ever mentions them explicitly, but the notes show clearly that he engaged with them, often responding to them. In addition to the rich panoply of Muslim thinkers, this edition’s notes show Rambam working in a tradition which includes Plato and Philo, not to mention biblical and rabbinic texts.

Later medieval Jewish writers often adopted a style termed leshon mishubetzet, embedding partial verses and bits of rabbinic writings in their own texts, as a form of stylistic homage to the earlier Jewish tradition. Rambam did not do that. His thousands of verses and rabbinic passages (where necessary, translated in Goodman and Lieberman according to Rambam’s use of them) were not mere adornments but part of the warp and woof of what he was crafting as a Jewish philosophical text. One sees that clearly in the first 50 or so chapters on biblical terms and expressions with which he opens his book and the last 25 or so chapters on ta’amei ha-mizvot with which he brings the work to a close. Indeed, he really was a rabbi!

Rambam was openly critical of several passages in Hazal, but the new translation with its notes show how respectful he was of the Sages generally. He fought hard to show how what they said made sense (at least most of the time). Apropos, Rambam thought (wrongly) that the Prophets of Israel and many later rabbinic Sages were philosophers. Pines dismisses this as a convenient fiction, a noble lie. In effect, reading Rambam in this Straussian fashion turns him into a liar. Of course, Rambam wrote esoterically (he tells us so himself). But why? For Pines and Strauss it was to protect himself by hiding the fact that he was “not a rabbi.” The Rambam of Goodman and Lieberman was much less esoteric than the Maimonides of Pines—and his esotericism was not aimed at protecting himself, but at protecting the masses from views which they could not understand.

Not being an Arabist, I will only make a few comments about the translations themselves. Pines’ English is notoriously wooden. Goodman and Lieberman have the advantage of being native speakers of English and master stylists. They further inform us that Rambam’s Arabic was informal, even colloquial, often conversational. Their very readable translation reflects that fact.

Goodman and Lieberman are also more theologically aware than was Pines. For example, Rambam occasionally uses the phrase al-Torah but more often the Arabic word sharia when speaking of the Torah (i.e., the Pentateuch). Pines invariably translates that as “the Law” while Goodman and Lieberman correctly translate it as “the Torah.” Pines’ Rambam sounds like a Protestant Christian (to be fair: there are a few places where the new translation follows Pines’ usage). Here is a brief example from Guide III:17 on theories of providence:

The fifth opinion is our opinion, I mean the opinion of our Law… it is a fundamental principle of the Law of Moses our Master, peace be on him… (Pines, 469)

Goodman and Lieberman on the other hand offer:

The fifth view is our own, the biblical view… it is a bastion of the Torah [sharia] of our teacher Moses… (380).

In this, Goodman and Lieberman agree with the Hebrew translations of ibn Tibbon, Kafih, Michael Schwarz, and Makbili/Gershuni. Pines’ commitment to literalism and consistency led him here (and elsewhere) into presenting misleading translations.

As often noted, the Pines translation is stilted; it is also wordy and often nearly incomprehensible without a dictionary near at hand. Let us look at an example, taken from the very beginning of the Guide. Pines delivers 84 words of plodding prose:

The first purpose of this Treatise is to explain the meanings of certain terms occurring in books of prophecy. Some of these terms are equivocal; hence the ignorant attribute to them only one or some of the meanings in which the term in question is used. Others are derivative terms; hence they attribute to them only the original meaning from which the other meaning is derived. Others are amphibolous terms, so at times they are believed to be univocal and at other times equivocal (5).

Pines sends his reader running to a dictionary in search of the meaning of “amphibolous” (and to wonder which “books of prophecy” are intended). Goodman and Lieberman’s economical 58 words are both more economical and more clear:

The first aim of this work is to clarify the meanings of certain terms in Scripture. Some of these have multiple senses, but the ignorant take them only in certain of those senses: although some are figurative, they only take them in the sense underlying the figure. Others are ambiguous, to be taken now at face value, now metaphorically (5).

Here is another example, drawn from Guide III:27. First, Pines’ 192 words:

The Law [al-sharia] as a whole aims at two things: the welfare of the soul and the welfare of the body. As for the welfare of the soul, it consists in the multitude’s acquiring correct opinions corresponding to their respective capacity. Therefore some of them [namely, the opinions] are set forth explicitly and some of them are set forth in parables. For it is not within the nature of the common multitude that its capacity should suffice for apprehending that subject matter as it is. As for the welfare of the body, it comes about by the improvement of their ways of living one with another. This is achieved through two things. One of them is the abolition of their wronging each other. This is tantamount to every individual among the people not being permitted to act according to his will and up to the limits of his power, but being forced to do that which is useful to the whole. The second thing consists in the acquisition by every human individual of moral qualities that are useful for life in society so that the affairs of the city may be ordered (510).

Contrast this with Goodman and Lieberman’s 98 words:

The Torah has two aims: material and spiritual well-being. Spiritual well-being comes when the masses, so far as they are able, attain sound beliefs, some stated explicitly, some symbolically, as when the general populace lacks the natural capacity to take in such things directly. Material well-being is won by improving human relations in two ways: (a) by checking wrongdoing—so not everyone may do just as he likes (cf. Judges 17:6, 21:25) but must keep to acts helpful to all—and (b) by everyone’s acquiring traits of character beneficial to society and conducive to civic order (420).

Bear in mind that these sentences open a 25-chapter section on ta’mei ha-mizvot. Guide III:27 introduces the reader to the idea that the mizvot have two aims. This is clear enough in Goodman and Lieberman, not clear at all in Pines. As is evident in the rest of the chapter (and in the 25 which follow), Pines’ “welfare of the body” means precisely what Goodman and Lieberman present: improved human relations. Pines’ literalism gets in the way of understanding Rambam.

Shlomo Pines and his translation of the Guide

Now, for a word about the commentaries: Pines offers none, while Goodman and Lieberman richly annotate almost every page. These annotations clarify Rambam’s meaning, locate sources in the Jewish and philosophic traditions, and occasionally take note of possible contemporary implications of Rambam. As one example of this, Goodman and Lieberman frame Rambam’s “harsh appraisal” about Africans in Guide III:51 to be a statement concerning culture, not race (516 n. 568).

Looking at the last four chapters of the Guide is a good way to bring this brief discussion to a close. Do these chapters teach us how to read the Guide as a whole (Goodman and Lieberman think so), or were they tacked on for some obscure reason known only to Rambam? Here is how Goodman and Lieberman translate the opening of that section: “The chapter I send you now contains no new themes beyond those in the rest. It serves only as a kind of seal. But it does spell out the type of worship that befits one who grasps God’s uniqueness, one who has come to realize what God truly is. It will guide towards such worship, man’s highest goal…” (515, emphasis added). Taking Rambam at his word, I once heard the late and greatly lamented Rabbi Jonathan Sacks point out that the whole point of the Guide was to lead us to these chapters, which, among other things, teach us how to read Keri’at Shema properly.

Pines, on the other hand (cxxii) rejects as “completely false” a similar interpretation. For him, it is not the point of the Guide to teach proper (i.e., philosophically sophisticated) Jews how to worship God. Having cited the opening of III:51 in Goodman and Lieberman, let us look at Pines’ version: “This chapter that we bring now does not include additional matter over and above what is comprised in the other chapters of this Treatise. It is only a kind of conclusion, at the same time explaining the worship as practiced by one by one who has apprehended the true realities peculiar only to Him after he has obtained an apprehension of what He is; and it also guides him toward achieving this worship, which is the end of man…” Goodman and Lieberman’s much terser translation makes clear the epistolary nature of the Guide; Pines emphasizes that the work is a “Treatise.” On Goodman and Lieberman’s translation, Rabbi Sacks’ comment makes sense: the Guide as a whole guides one how to worship God. For Pines, the Guide is clearly a philosophical work, but not so clearly a religious work.

In sum, if someone wants to study Rambam the rabbi who was also a philosopher, in contrast to Rambam the follower of Aristotle (as he understood him) who pretended to be a rabbi, Goodman and Lieberman are your best guides to the Guide.

I would like to close with a comment about Shlomo Pines, whom I never actually knew personally. My Israeli colleagues in the field of medieval Jewish philosophy are without exception menschliche people, who respect each other and get along with each other. (This is hardly the case in many other fields of Jewish studies.) In this I see the influence of Shlomo Pines z”l, widely known as a very decent human being, and in one way or another, the teacher of all of us.[2]

Menachem Kellner is Wolfson Professor Emeritus of Jewish Thought at the University of Haifa and founding chair of Shalem College’s Department of Philosophy and Jewish Thought.

[1] To be fair, in his Hebrew version of the introduction he uses the more neutral term miktzo’a (rather than “avocation”), see Shlomo Pines, Bein Mahashevet Yisrael le-Mahashevet ha-Amim (Mossad Bialik, 1977), 128. I presume only a vanishingly small number of readers—I may be the only one—would have any reason to check. On Pines’ introduction and his translation, see the essays collected in Maimonides’ “Guide of the Perplexed” in Translation: A History from the Thirteenth Century to the Twentieth, edited by Josef Stern, et al. (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

[2] My reading of Rambam as a deeply religious philosopher was influenced by several courses I co-taught with Rabbi Dr. Yizkhak Lifshitz at Shalem College, Jerusalem. I am grateful to the following for comments on earlier drafts of this post: David Gillis, Raphael Jospe, Daniel Lasker, Tyra Lieberman, and Jolene S. Kellner.

3 Comments

I am a long-time admirer of Professor Kellner, from whose writings I have learned much. I write to express a reservation, however, about his quick dismissal here of Leo Strauss’s interpretation of Rambam. Kellner writes that Strauss “famously held that Rambam could not have been both a rabbi and a philosopher and was much more a student of Aristotle than of Moses.” Kellner evidently disagrees with both propositions. What Strauss actually said in “How to Begin to Study the Guide of the Perplexed” is the following (p. xiv):

“One begins to understand the Guide once one sees that it is not a philosophic book – a book written by a philosopher for a philosopher – but a Jewish book: a book written by a Jew for Jews. Its first premise is the old Jewish premise that being a Jew and being a philosopher are two incompatible things. Philosophers are men who try to give an account of the whole by starting from what is always accessible to man as man; Maimonides starts from the acceptance of the Torah. A Jew may make use of philosophy and Maimonides makes the most ample use of it; but as a Jew he gives his assent where as a philosopher he would suspend his assent” (Strauss adds a reference to Guide II.16).

Strauss’s view finds support in the way Rambam ordinarily speaks of philosophy and philosophers: “the philosophers” in his usage are not Jews. Whatever one may think of Strauss’s esoteric interpretation of Maimonides, he helps us confront a very important issue (the fundamental difference between Jew and philosopher) that many interpreters overlook or gloss over.

I am grateful to David Levy for his comment and his kind words, but do not agree with his point at all. The point of much of my writing has been to deny that for Rambam, there is a “fundamental difference between Jew and philosopher.” For one reason among many for rejecting the Strauss/Levy position, I note Rambam’s repeated citation of “the philosophers” in support of positions held by Hazal in, for example, his Introduction to his Mishnah commentary and particularly in “Eight Chapters.” In H. Yesodei ha-Torah, among many other places, Rambam reads David and Solomon (among other biblical figures) as holding philosophic views. For a detailed refutation of Strauss/Levy see now A Guide to The Guide to the Perplexed: A Reader’s Companion to Maimonides’ Masterwork by Lenn Goodman (Stanford, 2024). My own attempt at refuting Strauss may be found in “Strauss’ Maimonides vs. Maimonides’ Maimonides: Could Maimonides have been both Enlightened and Orthodox?” originally published in Le’ela, December 2000: 29-36 (Hebrew version in Iyyun 50 (2001): 397-406) and available in Kellner, Science in the Bet Midrash: Studies in Maimonides (Academic Studies Press, 2009), 19-32. In general, the Rambam presented in Kellner and David Gillis, Maimonides the Universalist: The Ethical Horizons of Mishneh Torah (Littman, 2020), for whatever it is worth, would not agree with Leo Strauss and David Levy.

Many thanks to Professor Kellner for taking the time to reply to my comment and for providing the very useful list of references. I certainly agree with him (I presume Strauss would as well) that Rambam is at pains to emphasize the many points of agreement between philosophy and the Jewish tradition and that he maintains that the prophets possessed philosophic or scientific knowledge.