The Hidden Meaning of Esther’s Double Yud

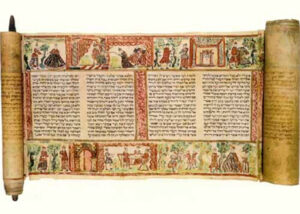

Reading Megillat Esther brings the pleasures of a tale well told, combining history, palace intrigue, the hero/heroine versus the villain, a threat of genocide, and a series of miracles, which subvert Haman’s evil plan. This fairytale-like account engages the reader’s thoughts to see how the Megilla will unfold, literally, as it is read.

Megillat Esther includes things that are hidden, many of which are later revealed. Vilna Gaon asserts that every verse of Esther discusses in some way the miracles that occurred. However, unlike the Exodus from Egypt, which openly revealed God’s strong hand and direct intervention, the miracles of Purim took place in a hidden way, through means that seemed natural1

For instance, Esther hides the fact that she is Jewish (2:20). Bigtan and Teresh hatch a secret plot to murder the king (2:21–22). Haman does not reveal the identity of the specific nation he is targeting (3:8). Our custom to wear masks and costumes on Purim to hide ourselves or disguise our identity reflects these themes.2

The Talmud adds to this theme of hiddenness by stating that Esther, Haman, and Mordecai are all mentioned in the Torah, but in a hidden way (Hullin 139b). Regarding Esther, the Talmud references the following verse which states, “Yet I will keep My face hidden (haster astir) on that day, because of all the evil they have done in turning to other gods” (Deut. 31:18). This term, often referred to as hastarat panim, serves as a verbal hint to the name “Esther” and associates her with hiddenness.

Perhaps the most striking example of hiddenness is the fact that God’s name does not appear even a single time in the entire text. This is certainly unusual for a book of Tanakh (Shir ha-Shirim being the only other example).

The Double Yuds in “Yehudim” and a Connection to Haman’s Plot

In the spirit and tradition of seeking the hidden in Megillat Esther, this essay will describe an approach to finding God in the text through the usage of the double yud in the word “Yehudim.” (יהודיים) Appearing a total of 38 times, the word Yehudim appears with a single yud 32 times (יהודים), as it is commonly spelled. However, on six occasions, this word is written in the text with two yuds, but pronounced as if it has only one, an example of keri and ketiv.

In the spirit and tradition of seeking the hidden in Megillat Esther, this essay will describe an approach to finding God in the text through the usage of the double yud in the word “Yehudim.” (יהודיים) Appearing a total of 38 times, the word Yehudim appears with a single yud 32 times (יהודים), as it is commonly spelled. However, on six occasions, this word is written in the text with two yuds, but pronounced as if it has only one, an example of keri and ketiv.

Several authorities, including Maharal, Tzemah Tzedek, and, more recently, R. Dovid Feinstein have provided interpretations for the significance of the extra yud. However, none of these explanations account for all six specific usages in situ. We will explain how the six occurrences of the double-yud “Yehudim” might correspond to the six miracles that God performed to reverse Haman’s sinister plan. Doing so will emphasize several special traits associated with the letter yud that make its addition an appropriate vehicle for this purpose.

The letter yud is a primary letter in God’s name that may be given to individuals who are in need of strength and resilience. Beneficiaries of a yud include Joshua, whose Hebrew name Hosea was prefixed with a yud to become Yehoshua in order to protect him from the negative advice of the ten spies.3 Pinhas also received a yud as the second letter of his name (פינחס) to strengthen him for his role in exacting justice on behalf of God.4 In this sense, the addition of the letter yud to Yehudim in Megillat Esther may be similarly seen as God sharing a part of His name with the Jews, imbuing them with the Divine in order to strengthen them as a nation.

In his comments to the first mention of Mordecai as “ish yehudi,” Rashi provides a distinction between the one and two yud spellings. He notes that the term yehudi is a geographic reference to an individual who was part of the exile of Judah, regardless of his tribe (as Mordecai was from the tribe of Benjamin, not Judah, but referred to here, nonetheless, as “ish yehudi”) (Esther 2:5). In this comment, Rashi references the plural form of this word as “yehudim” with one yud (as if written with a lowercase “y”). In contrast then, Yehudim with two yuds could be the plural of Yehudi, meaning a Jew in a more religious and cultural sense (as if written with an uppercase “Y”).

There are six components of Haman’s plot against the Jews, from the underpinnings of the plan through its execution, which are described and numbered here for reference:

First, Haman complains that: (1) the Jews are dispersed (“There is a certain people, scattered and dispersed among the other peoples in all the provinces of your realm”), and (2) they have a different religion and therefore do not obey the king’s orders (3:8).5

Haman then requests the authority to: (3) kill the Jews and (4) loot their possessions (3:13).

To facilitate the execution of the plan: (5) Haman offers to fund the enterprise (3:9). Finally, Haman adds his intention to: (6) hang Mordecai (5:14).

Reversing The Plot with the Double Yuds

As stated earlier, there is an awareness that God performed miracles for the Jews in Shushan, even if His name does not appear explicitly in the text. We reference this involvement in Al ha-Nisim, the add-on to our amida prayer on Purim, that begins with “For the miracles…” In the special paragraph for Purim, we describe how God, in His great mercy, reversed Haman’s plan by annulling Haman’s counsel, mixing up his intentions, reversing his acts, and hanging him and his sons.

This reversal is consistent with another important theme of Esther, “ve-nahafokh hu,” a turnabout (Esther 9:1). The Megilla declares that on the exact day that the Jews were to be destroyed, the plan was reversed and they triumphed over their enemies. All these activities and factors clearly point to God’s involvement.

We will now demonstrate that each appearance of the double-yud Yehudim corresponds thematically with one of the six miracles. Haman to fund the enterprise (5): The first use of the double yud is found in “And Mordecai told him all that had happened to him, and all about the money that Haman had offered to pay into the royal treasury for the destruction of the Jews” (4:7). Here, Mordecai reveals Haman’s plot to Hatakh with the hope of inducing Esther to intervene with Ahasuerus on behalf of the Jews. This conversation begins the undoing of Haman’s plot. Beyond mentioning the plot itself, Mordecai specifically mentions the money that Haman has proposed for the scheme, bringing to light a connection to a reversal of Haman’s planned funding.

Looting the Jews’ possessions (4): Next, we are told that Haman’s estate has been given to the Jews (“That very day King Ahasuerus gave the property of Haman, the enemy of the Jews, to Queen Esther,” 8:1). This directly reverses Haman’s plan. Instead of Haman looting the Jews’ possessions, his personal property became the property of the Jews.

Hanging Mordecai (6): In 8:7, we see the two yuds used in the context of Haman being hanged, an undoing of the plan to hang Mordecai (“I have given Haman’s property to Esther, and he has been hanged on the pole for scheming against the Jews”). Moreover, the term “ha-etz,” with the definite article, implies a reference to a specific tree, namely the one that was prepared for Mordecai’s hanging.

Killing the Jews (3): In 8:13, the Jews are given permission to defend themselves in battle against their enemies and prevent the deaths that Haman planned. We also see a textual parallel to Haman’s original plan to kill the Jews, which included writing an edict and distributing it via courier (3:12–13). Here, the same process of a written edict distributed by couriers is used to negate the original decree (8:13–14).

The Jews are dispersed (1): Verse 9:15 contains another description of the Jews going to battle to defend themselves. While this text appears similar to 8:13, cited above, one difference is that this verse begins with the word va-yikahalu, indicating that the Jews gathered. At this juncture, the Megilla seems to be emphasizing that the Jews are no longer a dispersed people, but rather a nation that is re-unifying. This use of Yehudim would therefore be associated with the reversal of Haman’s complaint about the Jews being a non-cohesive nation scattered about the kingdom.

The Jews have a different religion and do not obey the king’s orders (2): The sixth and final double yud appears in 9:18 where the Jews again gather as a unified nation (“nik’halu”) to celebrate Purim. Haman complained about our religious practices and observance of our holidays. Now, in the final turnabout, we received a new holiday as a result of Haman’s foiled plot.

Ha-Rav et Rivenu (He Who Fights Our Fight)

A careful study of Megillat Esther reveals a unique design within the Purim story, and a potential glimpse of God’s hand in performing miracles to strengthen and unify us. This design suggests how each of the six uses of the double yud in Yehudim could be associated through the text with a specific reversal act to one of the six elements of Haman’s plot.

The book of Job states: “God will deliver us from six troubles, but in seven no harm will reach us” (5:19). Consistent with this message, we see six purposeful interventions by God in Megillat Esther to save us from a six-fold villainous plot, the maximum allowable danger for the Jews, according to Job.

By describing this reversal in the order in which the double yuds appear, the plan is not negated in the order in which Haman formed it. Perhaps this can be explained by viewing the proposed reversal sequence in pairs:

- God first focuses on the money-related elements, by cutting the funding (5) and preventing the looting (4).

- Next, He prevents the killing and violence against us by stopping the hanging (6) and enabling the Jews to wage war against their enemies (3).

- Once calm has been restored, He reinvigorates us at a religious level by gathering us together from across the kingdom (1) and establishing a perpetual commemorative holiday for us (2).

In addition to being an organized and tactical military plan, these pairings appear to also correspond well to the four mitzvot of Purim: matanot la-evyonim, gifts to the poor; mishlo’ah manot, gifts of food that are exchanged between individuals; reading the Megilla; and celebrating with a festive meal.

The focus on the money parallels matanot la-evyonim. Fulfilling this mitzva shows gratitude for the fact that Haman’s money was not used as he intended and that our own money was spared from theft.

The reversal of the killing and violence (8:5 and 8:13), is immediately followed by a description of the messengers who were dispatched to spread the word that the Jews could avenge themselves (8:14). This connection between the war and the messengers could be seen as a hint to the mishlo’ah manot. In addition to being a sign of gratitude and celebration, this mitzva is most properly fulfilled using a messenger, since messengers play an important role in Megillat Esther.6

Finally, the post-battle gathering and celebrating could relate to the reading of the Megilla, which is preferably performed in public.7 The root word “k-h-l,” to gather, is present in both (1) and (2) in the form of va-yikahalu and nik’halu. In addition, the Purim feast relates to both (1) and (2) as well, in terms of the religious and celebratory themes described above that we partook in as a unified nation.

We have put forth a connective theory describing why the six double yuds appear in Megillat Esther, how they may prove God’s direct involvement in the Purim miracles, and how this hidden approach conforms to the overall style of the Megilla. In doing so, we hope to shed some new light on how God may be revealed to us in the Purim story and how He remains committed to the unity and safety of the Jewish people throughout history. Through this noteworthy use of the double yuds, He strengthened us and elevated us from a group of dispersed yehudim, to a unified nation of Yehudim.8

Phyllis Silverman Kramer holds a Ph.D. in Jewish Studies from McGill University, and has taught at the University of Haifa and Tel Aviv University. Mordecai Kramer holds a Bachelor’s degree from Yeshiva College and an MBA from McGill University. The authors are mother and son.

- Perush Ha-Gra, Esther 1:2.

- Tzvi Elimelech Spira, Sefer Benei Yissaskhar, Ma’amarei Hodesh Adar, 9:1.

- Rashi, Numbers 13:16, quoting Sota 34b.

- Yitzhak bar Yehuda Halevi, Pa’ane’ah Raza to Pinhas (see Sefaria to Numbers 25:7)

- These two complaints are grouped together based on Rashi to Megilla 13b (s.v. “de-mafki lay”) who describes Haman’s complaint to mean that the Jews were always using religion, Shabbat, and the Jewish holidays specifically, as excuses to not work and therefore not observe the laws of the kingdom.

- Mishna Berura, Hilkhot Megilla 695:18.

- Mishna Berura, Hilkhot Megillah, 690:62

- The authors thank and are indebted to R. Amnon Bazak, R. Zev Wiener, and Ezra Sivan, Ph.D., for their valuable feedback.