The Ongoing Relevance of the Classics

Yitzchak Blau joins Jeffrey Saks, Menachem Kellner, Chaim Waxman, and Shalom Carmy‘s discussion of Orthodoxy and the state of the humanities, striking a more optimistic note arguing for the significance of this literature – and the live possibility of encouraging our students to read it. (See the index of all columns inthisseries.)

Louis Menand’s harsh critique of two volumes extolling great books courses makes several claims. He argues that great literature does not make us better people, that the two works downplay the significance of science, that such courses encourage non-specialists who cannot read Italian to teach Dante, and reminds us that the whole discussion is not a contemporary issue but a recurring debate. I will respond to each point seriatim.

Reading the Western canon certainly does not guarantee moral growth. Like all tools, it simply has the potential to aid character development if utilized well. When Macbeth generates awareness of the dangers of ambition and Les Miserables inspires us with the integrity and courage of Jean Valjean they provide a powerful weapon in the arsenal of those striving to make the world a better place. One could also read them and remain ethically indifferent and emotionally untouched.

Reading the Western canon certainly does not guarantee moral growth. Like all tools, it simply has the potential to aid character development if utilized well. When Macbeth generates awareness of the dangers of ambition and Les Miserables inspires us with the integrity and courage of Jean Valjean they provide a powerful weapon in the arsenal of those striving to make the world a better place. One could also read them and remain ethically indifferent and emotionally untouched.

Science, particularly in the form of modern medicine, has done wonders for alleviating pain and suffering; indeed, we should extol the greatness of those engaged in medical research. Yet science proves impotent when it comes to instilling values and to analyzing the immeasurable.Hence, we need humanities.Note how many of the most insightful medical writers, Oliver Sacks, Atul Gawande, and Jerome Groopman, powerfully integrate a strong humanities component with their empathy for their patients. Since doctors, computer programmers, and scientific researchers often receive more lucrative jobs than English professors and poets, an emphasis on humanities does enhance a call for idealism over economic pragmatism.

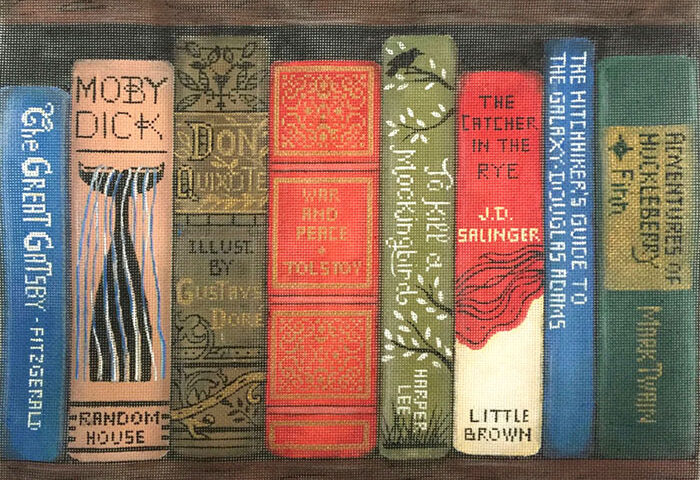

Clearly, every generation pursues wealth and requires intense encouragement to read Moby Dick.At the same time, modernity exacerbates certain additional problems. In the first section of his Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy (1958), William Barrett explains how philosophy tries to emulate the successes of modern science by endorsing narrow specialization and adopting the objective spectator perspective.A professor of philosophy of language specializing in the study of gerunds will find it difficult convincing students that his course impacts their lives. This is why we recognize the advantages of a wider range of reading even if it means consuming literature in translation. The best teachers are personally animated by their material. They convey with their enthusiasm that understanding Yeats’ “The Second Coming” truly matters. If professors act like a distant audience in the stands rather than engaged players in the game, we lose an important aspect of education. As R. Yitzchak Hutner would have it, we need nursing mothers giving of their essence and not professional cooks dumping the food on your plate (Iggerot u-Ketavim, no. 74).

Menand cannot see how postmodern relativism hurts this project. If we portray the classics as power plays pushing for political prowess, turn our courses primarily into critiques of insensitivity to minorities or LGBT individuals, and claim that the text has no meaning other than what the reader decides, why should our students think something deeply meaningful is going on? Given such a premise they correctly conclude that humanities do not matter.

Religious individuals express concern about their ability to successfully separate the wheat from the chaff. Will they be adversely affected by the broader exposure? My response is that no one can escape the need for discerning reading. Even those who only read books penned by Orthodox rabbis will encounter problematic statements they should reject. Cultivating good judgement is something we all require.

I receive insight and inspiration from the Western canon on an ongoing basis and could not imagine living a religious approach that outlaws such exposure. At the same time, I do notice a decrease in interest in the great works of Western philosophy and literature. In TRADITION’s own The Best series, some of the finest minds in Modern Orthodoxy have chosen movies, television shows, baseball games, jazz performances, and graphic novels for their columns.Yes, these items can have value but, to my mind, their depth pales in comparison to Middlemarch, Being Mortal, and Frost’s poetry. Even the literature choices are often shorter contemporary works rather than longer classics that have withstood the test of time.

Some think that the culture of social media renders any attempt to encourage our students to read longer works a quixotic venture. That is not my experience. First of all, shortened attention spans could motivate us to generate a counter culture. We can simultaneously make certain concessions and fight to move beyond TikTok and Twitter. Second, every year, several of my Orayta students read books of considerable length including one fellow who just completed David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (which weighs in at over a thousand pages). At least some contemporary students still have the capability for sustained attention—but their teachers need to provide a model for emulation.

Rabbi Yitzchak Blau, Rosh Yeshivat Orayta, is an associate editor of TRADITION.