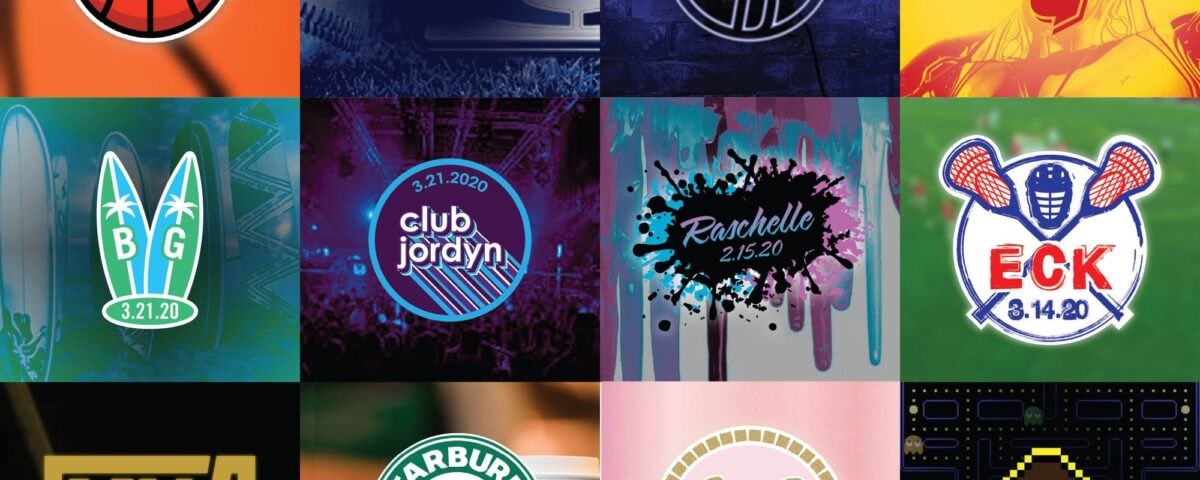

TRADITION QUESTIONS: Bar Mitzva Logos

Click here to read about this series.

Click here to read about this series.

What is it?

At Bar Mitzva and Bat Mitzvas, families celebrate the values they hope to transfer across generations, as they reflect upon their children’s accomplishments, character, and developing life-goals. In preparing for these celebrations, young people (and their parents) now invest much energy in designing a logo to splash across invitations, party décor, and swag. These personal logos commonly adapt the child’s initials to those of popular corporations that have established their images and messages through omnipresent advertising. Much like corporate branding, children use this exercise as an opportunity to define and in some way market their identities to friends and family by attaching themselves in some small way to a corporation’s public image.

Why does it matter?

In explaining why a Bar Mitzva should constitute a seudat mitzva – obligatory meal, R. Shlomo Luria (Yam Shel Shlomo, Bava Kamma 7:37) quotes Kiddushin 31a and Bava Kamma 87a. Upon hearing that the law follows Rabbi Hanina, who said that one who is commanded and performs a mitzva is greater than one who is not commanded and performs it, Rav Yosef (who was blind) said he would host a festive day for the Sages if the law followed the view that a blind person is obligated in mitzvot. R. Luria applies this idea to argue that a child becoming obligated in commandments, at Bar or Bat Mitzva, warrants a similar celebration.

Rabbi Hanina’s position sees greater good in a person’s identity as an object of command than in his or her individual choice. Modern Bar and Bat Mitzvas ironically juxtapose this message with that of consumer choice within the modern economy. While companies may compete for children’s attention, and that of their parents (and their wallets), they proselytize a common core message. Talbot Brewer, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Virginia, summarized that moral in a recent essay for The Hedgehog Review:

They tell us that consumption is a centrally important pathway to the happy life, and that a wide range of corporations have made it their purpose to help us along this pathway. That is, they provide a picture of the good life and an ideological justification of the prevailing economic order in terms of that picture of the good life. They invite us to enjoy a passive reconciliation with the social order.

To attach a modified corporate logo to a celebration of spiritual and divine calling highlights a failure to understand the subjugation of one’s inclination and desires necessary for that mission.

In his essay “Mitzva: A Life of Command,” R. Aharon Lichtenstein contrasts the life of consumption with that of disciplined service:

A person cannot…enter the world of avodat Hashem as if he were shopping in a department store. One shops in a department store precisely in response to one’s own needs and desires. It is part of self-indulgence and self-fulfillment. But he cannot shop around in God’s world. Either one understands what it means to accept the discipline of avodat Hashem or one doesn’t (By His Light, 50).

How might we communicate at life’s critical transitions that which lies beyond department stores and corporate advertisements, that is, the long tradition of religious ambivalence or aversion to a life dedicated to material acquisition?

What questions remain?

Bar Mitzvas and Bat Mitzvas had themes a generation ago. They were often sports teams or cartoon characters, tied to American childhood experience. What does their replacement by corporate identities say about America and the eclipse of its distinct youth culture?

Brewer writes:

The average six-year-old in the United States sees 40,000 commercial messages per year and can name 200 brands. Worldwide expenditures on advertising [were] expected to exceed $800 billion [last year] and to approach $350 billion in the United States alone. By comparison, the total annual budget of the Vatican for all purposes is about $860 million. Even if the Vatican devoted half of its annual budget to proselytism, its budget for reshaping the minds of the citizenry of the world would be barely more than 1/2000th of the amount spent each year on commercial advertising.

Is consumerism a competing belief system to religion? What would it mean to see consumer culture as a form of avoda zara?

How do our communities educate our children toward a lifepath that can compete with market-seeded desires and their fulfillment through consumer purchases?

Chaim Strauchler, an associate editor of TRADITION, is rabbi of Cong. Rinat Yisrael in Teaneck.