TRADITION Questions: Lonely Men of Courage and Humility

Click here to read about this series.

Click here to read about this series.

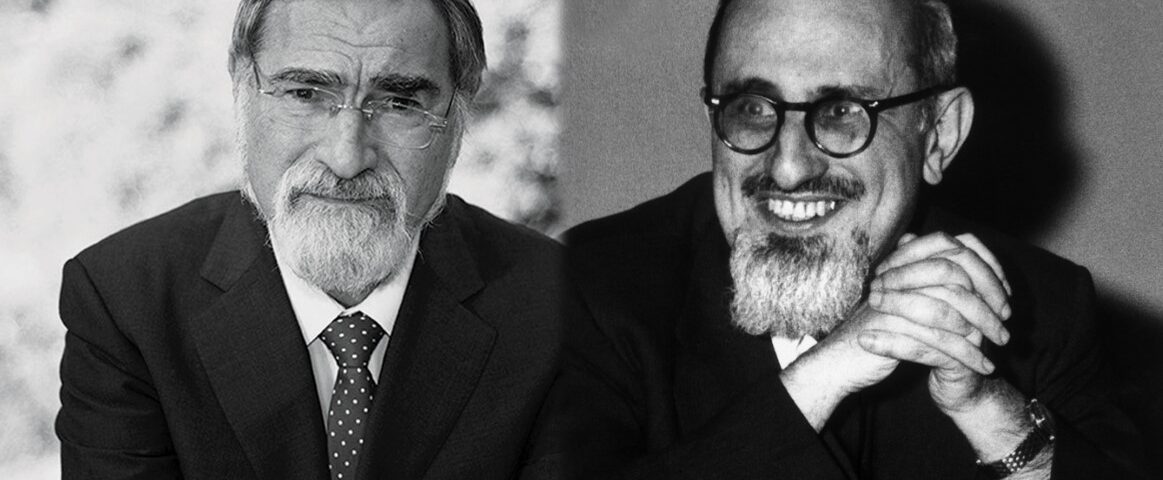

As the world marks the 4th yahrzeit of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks zt”l today, 20 Marheshvan (November 21) we turn our questioning gaze inward to his first significant publication, “Alienation and Faith” (TRADITION, Summer 1973). In the years since R. Sacks’ passing, TRADITION has offered a variety of content memorializing him and exploring his teachings. See the links appended below to review those items.

Visit the Rabbi Sacks Legacy site to participate in the Global Day of Learning.

What is it?

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’ first foray into the world of Jewish ideas and letters took place just over fifty years ago in the pages of TRADITION. His Summer 1973 article, “Alienation and Faith,” challenged the philosophical premise of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s “The Lonely Man of Faith,” that the Jew is doomed and blessed by an existence, that is divided, alienated, and lonely. R. Sacks contended that loneliness was, in fact, not endemic to the religious personality. Rather, it emerged from self-interest and sin:

The person in whom … self-assertion is the motivating force, cannot tolerate other selves, for they are potential obstacles to his self-realisation. So his only mode of relation is conditional and self-interested, and this is not fully to concede the separate reality of others. He is caught in the prison of the self… The man who lives his life in the Torah finds union; he who separates himself from it, separates himself from other men, even those closest to him. Loneliness is the condition of sin.

At the time he penned these words, Jonathan Sacks was 25 years old, having recently earned a Masters in moral philosophy from Oxford. In the essay, he foreshadowed many themes in his later writing, displaying the intellectual courage that would characterize his illustrious career. He confidently asserted the Torah’s benefit to Jews who were alienated from their faith:

The distance between the phenomenology of the Jew and that of secular man is what allows Judaism to hold out … redemptive relevance to the crises with which the Jew is faced when he is alienated from his faith.

He emphasized the centrality of community and living beyond the individual self:

[T]he love of the faith community is triadic, that Jew is bound to Jew in the identity of their relation to God, so that only in the context of a whole life of Torah and mitzvot does Ahavat Yisroel appear. It belongs instead to the explication of the opaque remark of the Zohar: “Israel, the Torah and God are all one.” This is not an ethical but an ontological statement, meaning that our very concept of separate existences lies at the level of religious estrangement; and that through a life not merely lived but seen through Torah, God’s immanent presence, His will (as embodied in the Torah) and the collectivity of Jewish souls are a real (in the Platonic sense) unity.

In response to the Rav’s empathy for the estranged Jew’s experience of loneliness, R. Sacks offers healing. He suggests that through Torah, community, and God, loneliness may be redeemed.

Why does it matter?

Despite the article’s politeness, the young Jonathan Sacks daringly offered a critique on the Rav. His essay suggests that the essential emotion at the core of much of the Rav’s work emerges from self-interested sin. He published the work in the pages of TRADITION, then the platform for every one of the Rav’s seminal works in English. How did the article come to be published, and why did it not generate more controversy?

Jonathan Sacks’ obscurity at the time of the article’s publication may explain how it flew under the radar. Its subtle and intricate argument may have confounded partisan rabble-rousers; they may not have realized what he was doing.

Rabbi Walter Wurzburger, then this journal’s editor, certainly understood R. Sacks’ argument. As one of the Rav’s foremost students R. Wurzburger would have appreciated its implication to “The Lonely Man of Faith.” Yet, he never repressed respectful critique of his teacher. Just the opposite. R. Wurzburger told R. Shalom Carmy that the Rav had warned him not to publish adulatory articles about him in TRADITION. Our questions regarding the article’s publication may serve to underscore a certain culture of Torah scholarship toward which each of these great men dedicated his life. In a society often beset by power and pride, Rabbis Soloveitchik, Wurzburger, and Sacks welcomed critique of their ideas in the name of Torah and truth. We would do well to ensure that they are not alone.

What questions remain?

After “Alienation and Faith,” R. Sacks did not write for TRADITION again until 1988, when he reviewed R. Soloveitchik’s recently published The Halakhic Mind. Why didn’t he contribute to our pages for those 15 years? Perhaps his involvement in L’Eylah (1975-2000), a British Jewish publication somewhat in the style of our own, the reason for this reticence?

In a 2015 “Covenant and Conversation” essay, he applied the core idea of “The Lonely Man of Faith” to Moshe:

Moses had been, for too long, alone. It was not that he needed the help of others to provide the people with food. That was something God would do without the need for any human intervention. It was that he needed the company of others to end his almost unbearable isolation… What Beha’alotecha is telling us through these three scenes in Moses’ life is that we sometimes achieve humility only after a great psychological crisis. It is only after Moses had suffered a breakdown and prayed to die that we hear the words, “The man Moses was very humble, more so than anyone on earth.” Suffering breaks through the carapace of the self, making us realise that what matters is not self-regard but rather the part we play in a scheme altogether larger than we are.

Did R. Sacks maintain his youthful critique of R. Soloveitchik’s understanding of loneliness, when R. Sacks himself rose to prominence and perhaps to the loneliness that often attends greatness?

Chaim Strauchler, rabbi of Rinat Yisrael in Teaneck, is an Associate Editor of TRADITION. He edited the Rabbi Sacks Bookshelves Project for TraditionOnline.org.

* * *

To mark the yahrzeit of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l and to celebrate his legacy, revisit some of the special content TRADITION has produced in his memory, and read some of R. Sacks’ own contributions to our pages.

- Rabbi Sacks’ print essays in TRADITION.

- David Shatz’s insightful testimonial to the impact of R. Sacks as an original Orthodox thinker.

- Over the course of many months, we explored the sources in western culture and scholarship on which Rabbi Sacks drew in crafting his own thought – visit the archives of the Rabbi Sacks Bookshelves Project.

- The TRADITION Podcast spoke with some of the distinguished British educators who authored essays in the Rabbi Sacks Bookshelves Project.

- Erica Brown discussed Rabbi Sacks’ teachings on home and family as pillars of Jewish education and transmission, through the prism of his Haggada commentary.

- Listen to the TRADITION Podcast on “The Philosophical Legacy of Jonathan Sacks” with Daniel Rynhold and Jeffrey Saks.

- Our downloadable High Holiday Reader collated many of TRADITION’s writings on Rabbi Sacks’ teaching.

- Read Alan Jotkowitz’s essay, “Universalism and Particularism in the Jewish Tradition: The Radical Theology of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks,” TRADITION 44:3 (Fall 2011).