Unpacking the Iggerot: One Daf to Rule Them All

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Unpacking the Iggerot: One Daf to Rule Them All / Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 1, #157

Summarizing the Iggerot

May one host a seudat mitzva (meal celebrating a mitzva) on the occasion of completing a book from Tanakh? Of course, one does not need license to arrange such a celebration, rather the halakhic question centers on whether such an accomplishment qualifies for a formal siyyum which can exempt firstborns from fasting before Passover and permit the consumption of wine and meat during the Nine Days preceding Tisha B’Av.

Normative practice only recognized the completion of a Talmudic tractate as a significant enough accomplishment to cross this halakhic threshold. This is supported by Abaye’s statement, “Grant me my reward, for when I see a young Torah scholar who has completed a tractate, I make a celebration for the rabbis” (Shabbat 118b). Likewise, Rema later codifies that “When one completes a tractate, it is a mitzva to rejoice and to make a meal, and it is called a seudat mitzva” (Y.D., 246:26).

Nonetheless, R. Moshe Yisoschor Goldberg suggested to R. Moshe Feinstein that there is indeed a basis for recognizing the completion of a book from Tanakh as a noteworthy accomplishment. Tur (O.H. 669) writes: “And it is the custom in Ashkenaz that the one who completes and the one who commences [the reading of the yearly Torah cycle] make pledges and invite their fellows to a celebratory meal for the completion of the Torah and its beginning.” Beit Yosef (ad loc.) expounds on this point by citing Hagahot Ashri, who in turn cites Or Zarua (Hilkkot Sukka #320) who locates the basis for this custom in Song of Songs Rabba (1:9):

The Holy One blessed be He said to him: “Solomon, you requested wisdom and you did not request wealth and property and the lives of your enemies. By your life, wisdom is granted you, and thereby, I will give you wealth and property”…. Immediately, “[Solomon] came to Jerusalem and stood before the Ark of the Covenant of the Lord. He sacrificed burnt offerings, he performed peace offerings, and he made a feast for all his servants” (I Kings 3:15). Rabbi Elazar said: From here it is derived that one makes a feast upon completion of the Torah.

R. Feinstein concurs with R. Goldberg’s assertion but disagrees with how he arrived at it. He argues that the annual completion of the Torah is not analogous to an individual or group who studies books from Tanakh, as the former is a uniquely national achievement collectively made by the entire Jewish people on Simhat Torah.

He instead identifies a different prooftext to support the same thesis. The Talmud records: “Rabbi Eliezer the Great says: Once the fifteenth of Av came, the force of the sun would weaken, and from this date, they would not cut additional wood for the arrangement” (Bava Batra 121b). Rashbam comments that “on the day they finished they celebrated, for on that day they had completed a great mitzva.” While, perhaps, they were not obligated to hold a formal celebration, if they did it would certainly constitute a seudat mitzva. Accordingly, holding a seudat mitzva is less about completing a particular tractate from the Talmud than it is about celebrating the investment of time into completing a significant mitzva, as the name seudat mitzva suggests (see Gra on Y.D. 246:76).

The responsum concludes with two noteworthy qualifications. While one can potentially count the completion of a book from Tanakh for a seudat mitzva, it would need to be studied in-depth. Moreover, he adds that “it is obvious, that this is so only when studied according to an authentic commentary (peirush emet), which is one of our great medieval rabbis.”

Connecting the Iggerot

In a follow-up resonsum (O.H., vol. 2, #12), R. Shemaryahu Shulman questioned why R. Feinstein did not root his thesis in the following Gemara:

When Rabbi Yohanan would conclude [study of] the book of Job, he said the following: A person will ultimately die and an animal will ultimately be slaughtered, and all are destined for death. [Rather,] happy is he who grew up in Torah, whose labor is in Torah, who gives pleasure to his Creator, who grew up with a good name and who took leave of the world with a good name. [Such a person lived his life fully,] and about him, Solomon said: “A good name is better than fine oil, and the day of death than the day of one’s birth” (Ecclesiastes 7:1) (Berakhot 17a).

Pnei Yehoshua elucidates that “when R. Yohanan would complete the Book of Job, he would generally hold a siyyum.” This would appear to be an explicit support for the concept of holding a seudat mitzva for a book of Tanakh.

R. Feinstein replied that there is a difference between how R. Yohanan studied Job and how we study it. The Sages of the Talmud expound on every last word and letter, leaving no stone unturned. If R. Yohanan were to serve as our paradigm, one would need to study Genesis with Midrash Rabba or Leviticus with the Sifra to even approach the level of analysis he brought to the study of each book. Therefore, the prooftext from the wood-gathering celebration provides more latitude, albeit one would still need to complete a book of Tanakh with more extensive analysis beyond a cursory scan of each Rashi.

Reception of the Iggerot

Considering the prevailing assumption that only a siyyum on a Talmudic tractate qualifies for a seudat mitzva (not including a brit and other mitzva celebrations), it is not surprising that other prominent rabbis disagreed with R. Feinstein’s position. For example, R. Shmuel Kamenetsky points to the aforementioned Rema who specifies a “tractate” when defining what constitutes a siyyum worthy of a seudat mitzva.

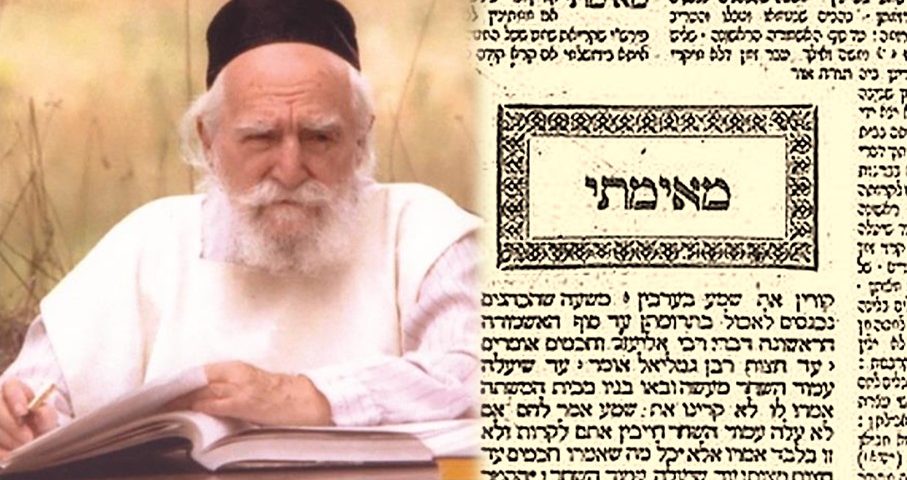

Where things get more interesting is regarding an iconic story about how R. Feinstein authorized a siyyum on the occasion of a single page from the Talmud! R. Shimon Finkelstein records the account as follows:

A gentleman from northern New Jersey started to become observant when he was past the age of 60. He told a friend that he felt despondent because, when his time was over, he would have to face the Heavenly Court without having amassed any Torah knowledge. The friend suggested that he drive to the Yeshivah of Staten Island from time to time—surely one of the students would be glad to teach him. So it was. He went to the yeshivah once a week for an hour of learning. He found it very difficult, because he had no Torah background and was not of an intellectual bent; however, after four years he glowed with pride at having mastered his first “blatt gemara.” One of the students told the story to Reb Moshe, who said that for this man, a single blatt was as much of an accomplishment as for a scholar to complete an entire masekhta. The Rosh Yeshivah asked the talmidim to celebrate the occasion with a seudas mitzvah) which he, too, would attend. The seuda was festive indeed, with Reb Moshe adding his own words of blessing and congratulation. With tears in his eyes, the “guest of honor” rose to thank everyone for making his life so much more meaningful. He said, “Now I am not afraid to die” (Reb Moshe [Artscroll], 287).

Similar stories appear in various works, which would suggest either that people making a siyyum on a single page were a regular occurrence in R. Feinstein’s orbit or, more likely, that the story has been retold with variances—sometimes for rhetorical flourish.

For instance, in the Haggadah shel Pesah: VaYaged Moshe (pp. 24-25), the story was about a penitent father who asked his yeshiva-educated son to help him learn from scratch. After an entire year, he eventually completed the first page of Tractate Megillah and asked R. Feinstein if he could make a siyyum, to which he replied that they should go ahead with it “and I too will join this seudat mitzva.” The story concludes that following the siyyum, that very night, this man passed away (implying that he had accomplished his mission in this world and was ready to depart to the next world). R. Feinstein eulogized him, “There are those who acquire their [share in the] world [to come] with one moment [of repentance] and there are those who acquire their [share in the] world [to come] with one daf!”

The punch-line changes yet again in R. Reuven Feinstein’s retelling (Zkeinekha Yomru Lakh, p. 67), in which the story concludes that his father, R. Moshe Feinstein, instructed that this man’s memorial stone mention that he had studied the Talmud in his old age. It is also noteworthy that R. Reuven Feinstein’s version makes no dramatic claim of the man immediately dying subsequently to his siyyum.

Both the Artscroll Reb Moshe biography and VaYaged Moshe versions employ the term seudat mitzva. Yet, R. Reuven Feinstein is careful to avoid it. He adds in parenthesis: “And I do not know if [R. Moshe Feinstein] would permit consuming meat for a siyyum such as in this case— perhaps it was merely done to provide joy and to encourage this individual in his studies.”

However, Sefer Yoma Tava le-Rabbanan (p. 32), a 376-page work on the laws of siyyumim, seems to take the story at face value, and assumes that R. Feinstein considered a siyyum on a single page of Gemara to qualify as a bone fide seudat mitzva. Rather than disputing the specifics of the account, he instead invokes common practice and asserts that “the custom of the world is to exempt the fast of the firstborn or permit meat during the nine days only with the completion of a Talmudic tractate.” In other words, R. Feinstein may very well be right, but it is simply not the accepted practice. Indeed, a typical Gemara will conclude with the text of a Hadran prayer, while one would be hard-pressed to find one at the end of a volume from Tanakh—although, see one proposed text of a Tanakh Hadran at Sefaria.

Reflecting on the Iggerot

R. Feinstein is recorded to have had a relatively lenient approach to allowing siyyumim made during the Nine Days to permit the consumption of meat (see Nitei Gavriel, Bein ha-Metzarim, vol. 1, ch. 41, par. 4, and Mesoret Moshe, vol. 1, p. 172, and vol. 3, pp. 151-152). Reportedly, he was not too concerned with the restrictions of the Mishneh Berurah (551:75-76) and earlier authorities, who opposed deliberately scheduling a siyyum to coincide with the Nine Days and also limited the attendance.

This is, perhaps, consistent with how he articulated his philosophy of the essence of a siyyum. In Iggerot Moshe (Y.D., vol. 2, #110), he points back to the Talmudic passage in which Abaye organized a siyyum for another scholar’s Torah accomplishment, even though he had no personal involvement. This is because “the joy of the siyyum of a tractate is not just that of those who completed it but for all who study Torah.” Likewise, when he addressed a siyyum of Daf Yomi participants he stated “that even the Torah study of an individual is worthy for all the Jewish people to celebrate.” (This is, perhaps, conceptually similar to how he permitted guests to attend a wedding during sefira if it was permissible according to the groom’s custom, as they are subsumed within his simcha; see Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 2, #95).

The Mishnah in Avot (3:8) states something perplexing: “Rabbi Dostai ben Rabbi Yannai said in the name of Rabbi Meir: whoever forgets one word of his study, scripture accounts it to him as if he were mortally guilty…” R. Feinstein reportedly remarked, “I don’t understand this forgetfulness. How is it possible to forget something?” This, too, is an even more perplexing assertion. Yet if we look at his homiletics, we can identify an explanation for both the severity and incomprehensibility of forgetting:

For we also learn to guard ourselves from forgetfulness, as there is a prohibition to forget even one matter from one’s studies (Avot 3:8). This is on the basis that a person needs to feel the Torah in his heart until the point that his entire body and will are tied to the Torah and mitzvot, and then he will remember, for a person does not forget the essence of his body and will…. (Darash Moshe, vol. 1, p. 160).

Further expounding on this point, his son R. Reuven Feinstein wrote in a memorial volume (Sefer Zikaron le-Zikhro HaGaon Rebbi Moshe Feinstein, published by Yeshiva of Staten Island, pp. 1-2):

My father, my teacher zt”l through his great classes and numerous responsa, became famous in the world for his wonderful knowledge of the Torah…. And although he was certainly given an enormous power of memory from Heaven, he would say of himself that it was not by natural proficiency that he earned his memory of the Torah, but rather his great regard for the Torah that enabled him to remember what he was able to remember, and he would demand that we also have the same high regard for the Torah as he did…. Likewise, when a person forgot what day of the week it was and did work on Shabbat, the forgetfulness did not come to him except because Shabbat did not have the proper importance to him [and therefore the Torah requires him to atone even for an inadvertent transgression]. For matters which are important and days that are important are not forgotten. He added and argued to the yeshiva students that we see that the rich man does not forget where he put “ahunderter” [a hundred dollars], and likewise, everything that a person needs for his needs and livelihood is not forgotten by him, as it is a pearl in the mouth of our Sages in Avot that forgetting one’s studies engenders a willful violation.

In R. Feinstein’s writings and thought, few themes are as salient as his love and dedication for Torah learning. It was not about the quantity, but the quality of one’s relationship with God and His Torah that was paramount. The same R. Feinstein who nonchalantly made his one-hundred-and-first siyyum on the Talmud for the second time (i.e., 202 times), also recognized the accomplishment of a single Jew mastering the first page of a tractate or book of Tanakh as worthy of public recognition and celebration. As another Mishna in Avot (5:23) put it: “Ben He He said: According to the labor is the reward.”

Endnote: Regarding the Fast of the Firstborn when Passover falls out after Shabbat, see Iggerot Moshe (O.H., vol. 4, #69). See Mesoret Moshe (vol. 3, p. 69) about whether to perform the siyyum during the meal or prior to it. See also Mesoret Moshe (vol. 4, pp. 547 and 550) for speeches R. Feinstein gave in honor of a particular siyyumim. He further addresses the concept of forgetting one’s learning in Iggerot Moshe (Y.D., vol. 1, #141; cf. ibid., vol. 2, #110 and Kol Ram, vol. 2, p. 288). Similar to how he recognized a siyyum on a book of Tanakh, R. Feinstein also authorized a bona fide seudat mitzva for the study of Mishnah as well (see Mesoret Moshe, vol. 1, p. 148, and Zkeinekha Yomru Lakh, p. 67).

Note to readers of the series: With this final installment of “Unpacking the Iggerot” for the season we make a “siyyum.” I am grateful for the opportunity to publish a regular column with TRADITION and I hope to adapt all of these chapters for a future book. In the meantime, my Hebrew anthology of R. Moshe Feinstein’s teachings on Pirkei Avot, to be titled “Meorot Moshe” is due to appear in the coming months. “Unpacking the Iggerot” will make a “Hadran” and return in September, dateline: Allentown.

Moshe Kurtz is the incoming rabbi of Cong. Sons of Israel in Allentown, PA, the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later.