Unpacking the Iggerot: Pink Pistols and Pikuah Nefesh

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Pink Pistols and Pikuah Nefesh / Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 4, #75:3

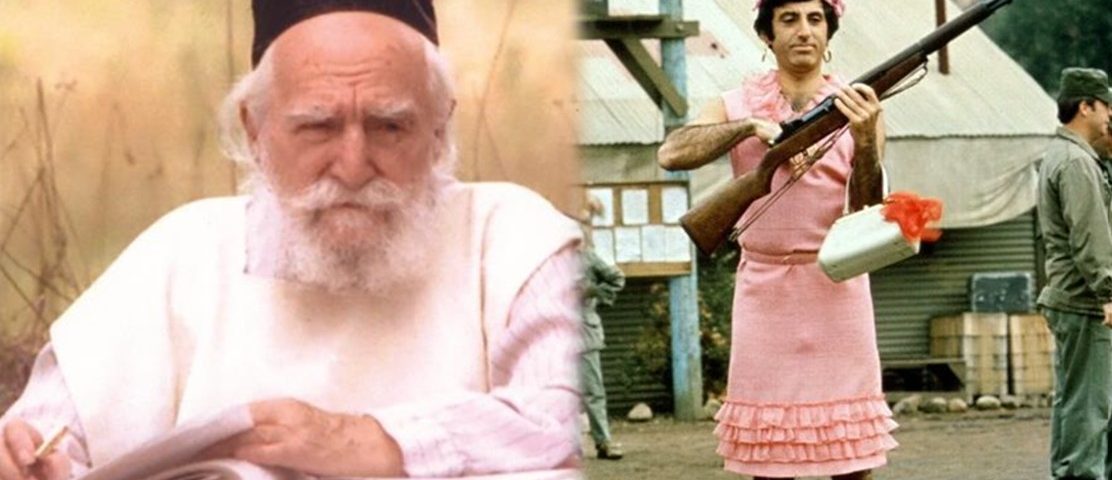

With the arrival of Purim we are reminded of the Torah’s prohibition of lo yilbash (imperfectly translated as “cross-dressing”) and its applicability or not to certain holiday costumes. This halakha has a wide variety of applications, including men using cosmetics and women carrying weapons (and, more generally, serving in military roles). As we undertake this week’s exploration le-halakha ve-lo le-ma’ase, we are reminded that too many Israeli soldiers, men and women, will be dressed in uniform this Purim instead of in silly costumes, as they defend the Jewish people and State.

Summarizing the Iggerot

R. Moshe Feinstein generally refrained from opining on issues related to Eretz Yisrael, asserting that there is no shortage of Torah scholars who can rule on their own local issues (Meged Givot Olam, vol. 1, p. 55). However, when a question came from his relative and editor of several of his published works, R. Shabtai Rapaport, he was not one to send him off empty-handed. R. Rapaport inquired whether it would be permissible for a woman living in Gush Etzion to carry a pistol when leaving her settlement. The potential halakhic issue with this emerges from the Talmud, which records the following:

Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov says: From where [is it derived] that a woman may not go out with weapons to war? The verse states: “A woman shall not wear that which pertains to a man, and a man shall not put on a woman’s garment” (Deuteronomy 22:5), [which indicates] that a man may not adorn himself with the cosmetics [and ornaments] of a woman, (and similarly a woman may not go out with weapons to war, as those are for the use of males) (Nazir 59a).

From this passage, it would appear that a woman wielding a weapon is in violation of an expanded definition of cross-dressing or lo yilbash. R. Rapaport, however, suggests four grounds for leniency:

1) If there is a reasonable risk of an ambush, carrying a firearm constitutes pikuah nefesh, the preservation of life, which supersedes lo yilbash.

2) In accordance with Taz (Y.D. 182:4) and other commentaries, one does not trigger the prohibition of crossdressing if being done for utilitarian purposes. If a man only has access to a woman’s raincoat, wearing it to protect himself from the elements is serving a functional purpose and would not be in violation of lo yilbash. Likewise, it can be argued, that a woman who carries a firearm is doing so strictly for the practical purpose of self-defense, rather than attempting to adopt the role or appearance of her male counterparts.

3) R. Elazar ben Yaakov stated that “a woman shall not go out to war with weaponry.” War is a collective military endeavor. Traveling to visit a friend, pick up the groceries, or run an errand is not “going out to war,” even if she brings along a gun for the ride.

4) There is room to distinguish between a larger firearm that is typically reserved for the military versus a hand-gun which can more plausibly be classified for self-defense.

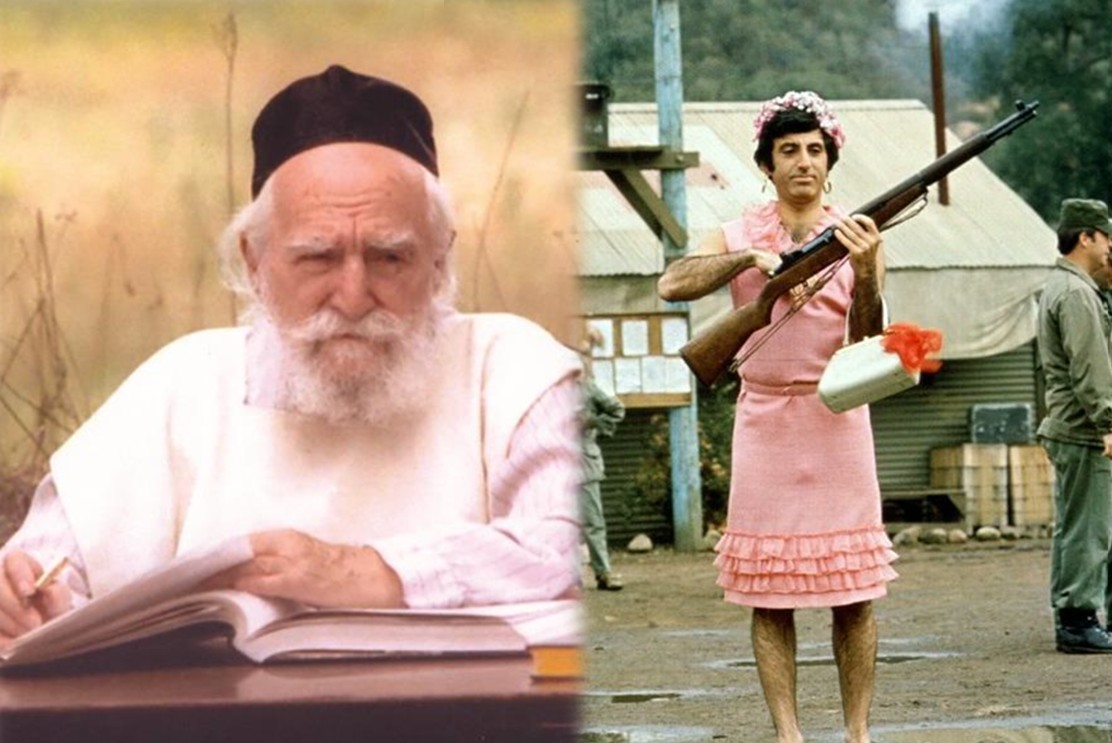

R. Feinstein challenges R. Rapaport’s second suggestion, that since the woman is not wearing the weapon for aesthetic purposes it would not be in violation of lo yilbash. He asserts that the proscription against women going out to war with weaponry, while classified under crossdressing, is an independent issue. In fact, if a woman were to wear the firearm for fashionable purposes it would actually not be subject to lo yilbash. Rather, it is only when a woman wields a weapon to give off the appearance of masculinity that it would run afoul of this proscription. As one woman who attended one of my previous presentations put it, R. Feinstein would have seemingly approved of her carrying a pink pistol.

R. Rapaport had also suggested that the very act of entering battle was prohibited under lo yilbash. And while R. Feinstein agrees that women are not beni milhama, qualified to enter combat, he avers that technically it does not fall under lo yilbash. He argues, based on his reading of Rambam, that the actual issue identified in the Gemara was with a woman wielding a weapon. The clause about “going out to war” is a red herring, as the prohibition of a woman wielding a weapon would apply even during peacetime.

After some additional analysis, he ultimately permits the women to take along the weapon based on the aforementioned distinction between a pistol and a military-style rifle. He also introduces a novel distinction between fighting in a military campaign versus participating in a limited skirmish; the latter is arguably not off limits to women. Of course, he notes that much of this is moot if the situation meets the threshold of constituting pikuah nefesh, the necessity to preserve life. And, notably, he writes that these dangerous circumstances should still not prevent women from going about their normal lives and traveling to where they need to—even if it means carrying a weapon.

(As a postscript, R. Feinstein cites R. Akiva Eiger to elucidate that Yael, in the Book of Judges, opted to use a tent peg instead of a sword, since Sisera was already unconscious and no longer posed a threat for the moment. Therefore, absent any immediate danger, the prohibition of lo yilbash applied and therefore she sought a non-weapon to deal the lethal blow.)

Connecting the Iggerot

The locus classicus for R. Feinstein’s approach to lo yilbash is found in an earlier 1954 responsum published in Iggerot Moshe (Y.D., vol. 1, #82) regarding whether a man may take a pill that would restore his hair to its original color. Plucking grey hairs and attempting other methods to make one appear more youthful is classically understood to be a feminine practice. While the act of taking a pill is not inherently gendered, R. Feinstein argues that lo yilbash is assessed based on the result—and indeed the pill’s effect is that it provides the man with a more youthful appearance, thereby running afoul of lo yilbash. He adds that despite there being no immediate chang, the indirect nature (grama) of taking the pill does not mitigate a sin that is assessed based on result, not the method it is achieved.

In a follow-up responsum (Y.D., vol. 2, #61), he applies a similar frame of analysis to the proscription against a man gazing in a mirror to groom himself. He argues that it is not the act of looking in the mirror, but rather the result his feminine-like fixation on perfecting his physical appearance. He does, however, provide a dispensation for a man who is interviewing for a job to dye his greying hair, out of concern that an older appearance would diminish his employment prospects. He invokes the same Taz referenced in the initial responsum, that cross-dressing for a strictly utilitarian purpose as opposed to an aesthetic one would not be in violation of lo yilbash. Granted, the applicant is not altering his appearance in a flagrantly deceptive manner, which would constitute ona’ah. (We should also note that R. Feinstein addresses at what age a child must be dressed in gender-appropriate clothing, see E.H., vol. 4, #62).

Seemingly in line with this reasoning, R. Aharon Felder reports that R. Feinstein permitted a man to make use of a parasol designed for women, as it serves a pragmatic purpose. Moreover, he permitted a young man to dye his premature white hair, should he feel humiliated by it and is concerned that it would negatively impact his dating prospects (Reshumei Aharon, vol. 1, p. 42).

R. Feinstein was also asked by R. Elimelech Bluth regarding a man who wished to dye his hair to help improve both his work-life and marital-life. R. Feinstein responded that the general issue of dyeing is that it demonstrates vanity and an obsession with superficiality. However, both vis-a-vis his professional and marital circumstances it can be argued that he is enhancing his appearance for pragmatic purposes. Nonetheless, he expressed some doubt about whether this man coloring his hair would be the silver-bullet improvement his marriage that he hoped it would be (Mesoret Moshe, vol. 1, p. 248; see also ibid, vol. 4, p. 211).

While R. Feinstein technically permitted men to dye their hair for practical purposes, R. Yitzchak Pollack reports that he had still advised one inquirer who was concerned for being terminated due to his advanced age, “do not dye your hair, rather I bless you that your employer will not dismiss you.” And as the story goes, this man who heeded the Gadol ha-Dor’s advice merited to retain his employment until a ripe old age (Koveitz Kol Torah, vol. 54[Nissan 5763], p. 73).

Reception of the Iggerot

As noted, R. Feinstein’s dispensation for a man to dye his hair for professional purposes was predicated on Taz and others who espoused that crossdressing for functional purposes would not contravene lo yilbash. R. Moshe Shternbuch (Teshuvot ve-Hanhagot, vol. 1, #461) argues, however, that R. Feinstein’s inference is erroneous. Taz reasoned that wearing the opposite gender’s clothing to protect from the elements would be permissible since the cross-dressing taking place does not serve to enhance the wearer’s appearance. However, a man dying his hair to secure employment, while done for a practical end, is still being done with the goal of improving his physical features and should therefore still be in violation of lo yilbash—even according to the Taz.

Regarding our initial responsum, the Sefer Bigdei Ish (pp. 176-177) raises several potential objections to R. Feinstein’s permission for a woman to carry a weapon while leaving her settlement. First, if traveling is so dangerous that it rises to the level of sakanat nefashot, then, he suggests, while lo yilbash would indeed be superseded, it would still be forbidden to leave in the first place as doing so is an endangerment to one’s life!

Moreover, he questions why R. Feinstein took it for granted that this woman needs to travel in the first place and his proceeding to factor it in as a basis for leniency. Indeed, he argues that if daily life is so unsafe, perhaps it would incumbent upon the residents to relocate. As an aside, he also notes that some have suggested that rather than holstering the pistol, a potential way to mitigate lo yilbash would be for the woman to keep the gun in her handbag instead. (The Sefer Bigdei Ish, p. 11, fn. 31, also addresses R. Feinstein’s ruling regarding the minimum age for children to be accustomed to gender-appropriate clothing.)

Despite the questions raised with R. Feinstein’s ruling, it is noteworthy that R. Ovadia Yosef (Yehaveh Da’at, vol. 5, #55) cites the reasoning of the Iggerot Moshe in his permission to female Israeli teachers to keep firearms on hand, provided it is done in a manner that does not compromise religious standards of modesty (tzeniut).

Reflecting on the Iggerot

One other remarkable point made by Rabbis Feinstein and Rapaport in the initial responsum was the distinction between a hand-gun versus a weapon more typically associated with military use. One aspect of the debate surrounding the Second Amendment in American discourse is the distinction between firearms that can more plausibly be used for self-defense versus fully-automatic rifles that can be used to inflict mass casualties. Ostensibly independent of this matter, R. Feinstein recognized such a distinction. He was not oblivious to the general debate surrounding gun-control. Reportedly, he lamented how easy it is to purchase a gun in America and how it has led to many deaths. He accused a select group of powerful and wealthy individuals who have prevented the government from passing new legislation to tighten the restrictions (Mesoret Moshe, vol. 1, p. 502).

The topic of lo yilbash has broad applications and classically has come to a head on Purim, a time of ve-nehapokh hu, when roles are reversed. This has been one of the flashpoints for understanding the parameters of lo yilbash—and while R. Feinstein did not appear (to my knowledge) to issue a ruling on this matter, his analysis of the general topic has played a critical role. I have written about this more generally in my article “Cross-Dressing and Cross-Conduct: When Lo Yilbash Meets Contemporary Western Culture” (The Lehrhaus, March 2022).

Endnote: See Dibberot Moshe (Yevamot, vol. 1, pp. 153, 575) and Mesoret Moshe (vol. 3, p. 216) which contain further elaborations on R. Feinstein’s approach to lo yilbash. The Sefer Ma’aneh le-Iggerot (#117, pp. 246-252) offers several counterpoints to R. Feinstein’s analysis. The reader might also be interested in seeing his responsum regarding shaving on hol ha-moed, in which he appears to recognize the changing social dynamics for male grooming (Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 1, #163). I found it noteworthy, however, that in his responsum (O.H., vol. 2, #79) about a Jewish thespian having a non-Jew remove his stage makeup on Shabbat, he does not raise the issue of lo yilbash in his analysis. And in his responsum about whether dieting constitutes self-harm (H.M., vol. 2, #65) he matter-of-factly assumes that it would be women undertaking it for aesthetic purposes, while men would only consider it for health purposes (cf. H.M., vol. 2, #66 and Mesoret Moshe, vol. 1, p. 248). This would be consistent with his (and arguably the Talmudic tradition’s) ethos of lo yilbash, which associates fixation on appearance with femininity. Finally, regarding other responsa related to the dangers involved in defending Israeli life, he provided guidance as to how soldiers should go about performing their duty in respect to Shabbat in Iggerot Moshe (O.H., vol. 5, #26 and #30).

Moshe Kurtz serves as the Assistant Rabbi of Agudath Sholom in Stamford, CT, is the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later.

Prepare ahead for the next column (March 27) on truth-telling and shidduchim: Iggerot Moshe, E.H., vol. 1, #91