Unpacking the Iggerot: Read All About It?

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

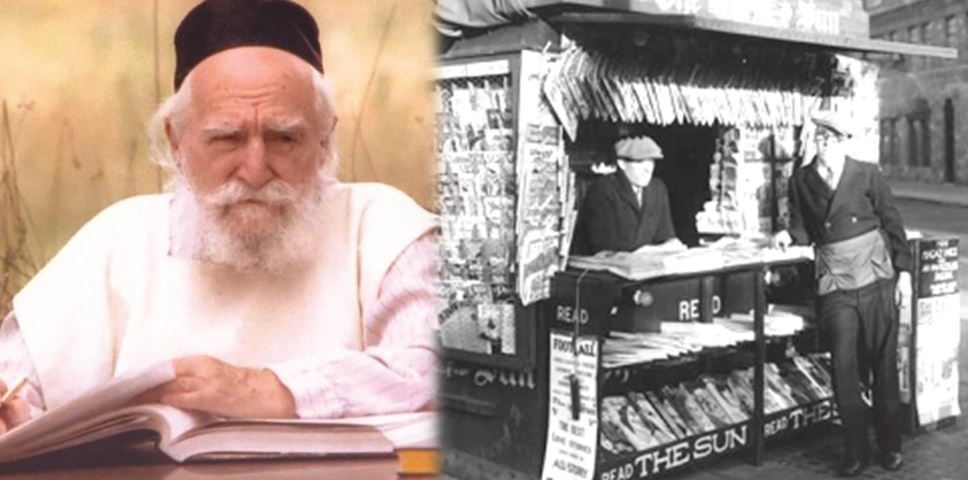

Did the Gadol ha-Dador Read Newspapers? / Iggerot Moshe, Orah Hayyim, vol. 5, #22:3

Summarizing the Iggerot

In a series of mini-responsa, R. Moshe Feinstein was asked whether a newspaper, particularly a business digest, is muktze and may not be moved on Shabbat. The response was recorded as follows:

These newspapers serve no general function—even that of stopping up a bottle, as we don’t generally use it for that. Therefore in the house of those who do not read these newspapers it would constitute muktze. And it is correct to refrain from reading newspapers which are dedicated to business. However, for those who are not aware of the prohibition and read them there would be no violation from a muktze standpoint..

By “general function” he isn’t addressing the utility of a newspaper as a platform to deliver “all the news that’s fit to print.” Rather, within the technicalities of hilkhot muktze. Whether any given object has a useful, permitted purpose on Shabbat (his example here, something which could serve in place of a cork on a bottle). Leaving the muktze issue aside, it would appear that R. Feinstein was in principle comfortable with allowing for the general news to be read on Shabbat.

Connecting the Iggerot

References to newspapers incidentally appear in several responsa (E.H., vol. 1, #41-42, 50) regarding post-war agunot cases in which news reports are sought to introduce evidence ascertaining a husband’s death. In a responsum regarding genetic testing (E.H., vol. 4, #10), R. Feinstein recommends advertising in the papers the importance of genetic screenings to prevent matching couples who are at risk of, God forbid, having a child with Tay-Sachs. Reference, this time to newspapers produced by “kosher Jews,” is also made in a discussion about the status of Hebrew letters on various documents (Y.D., vol. 3, #120).

At the end of Yoreh De’ah (vol. 2, #76), R. Feinstein addresses whether one may bring a Hebrew newspaper or dictionary into the bathroom. He rules that there is no formal prohibition, even if the letters for some reason were written to the standards used of Torah, tefillin and mezuza scrolls. As an aside he remarks that reading most newspapers, even printed in Hebrew—which contain matters “not worth writing about in all cases”—may not be proper in the first place. This may have been part of the inspiration for the joke told in certain circles that “the question isn’t whether you may bring the Jewish Press into the bathroom, it’s whether it may be removed from there!” Though, as we will see, R. Feinstein likely did not object to the mostly innocuous Orthodox newspapers.

Reception to the Iggerot

Those following the lead of the Mishneh Berurah adopted a more stringent stance on newspapers, especially on Shabbat, based on the Shulhan Arukh (O.H. 307:16):

One may not read on Shabbat secular books of phrases and parables, books of passion (such as Sefer Emanuel), and war books. One may not read them during the week as well because it is a “sitting of scoffers” and because one is removing God from one’s mind. Books of passion have an extra prohibition of arousing one’s evil inclination, and therefore the authors, the copyists, and of course the publishers cause the masses to sin.

(Although the Shulhan Arukh does not address newspapers, which hadn’t been invented in his lifetime, later poskim point to this paragraph to arrive at stringent positions regrading reading the news.)

R. Yehoshua Yeshaya Neuwirth (Shemirat Shabbat ke-Hilkhata, 29:46-47), however, espouses a similar position to R. Feinstein, distinguishing between reading the general news versus business-related items. For those who subscribe to the Wall Street Journal, perhaps the difference might be between reading Section A, which is about domestic and world news versus Section B, which centers on the latest market updates. (Though, it is not the cleanest distinction, as there are general interest articles in the latter as well.) Similar to what we noted in the previous section, R. Neuwirth appends in a footnote (#117) that some contemporary newspapers contain inappropriate material which would be forbidden to read anytime.

Talmudists are generally hesitant to relegate a halakhic disagreement to a mere matter of metziut, that is, a misunderstanding of the facts on the ground. Rather, the default assumption is that both parties are privy to the same data and disagree on its interpretation. Yet, oddly enough, there are members of R. Feinstein’s inner circle who could not seem to agree on the biographical question of whether he read newspapers or not. For instance, one disciple praised his teacher who “did not read newspapers—and remarkably he [still] knew everything.” His son-in-law, R. Dr. Moshe Dovid Tendler (“Royalty, Humility, and Genius”), however, contended that R. Feinstein was indeed open to such outlets and lamented what he perceived to be a distortion of his father-in-law’s personality:

There are many anecdotes told about Rav Moshe. Most of them are apocryphal. Some of them are even debasing. Above all, Rav Moshe was a normal healthy personality, a normal husband, a normal father, a normal grandfather who took great pride and joy in his family. Rav Moshe did not overtly display any special tzidkus or chasidus. His only publicly displayed midah was his gentleness. In the evening he would often go for [a] walk with his wife and stop in the local candy store to buy a glass of soda. He read the newspaper every morning at the breakfast table, whatever newspaper it might be—the socialistic Forward, or the Tag, or the Morning Journal and then the Algemeiner Journal. Stories reporting unusual behavior on the part of Rav Moshe are by their very nature false and insulting, for they are intended to pervert his most important message for our generation; and that is, mastery of Torah does not distort the human personality, it only adds grace and glory to it.

He further articulated this point in “An Interview with Rabbi Dr. Moshe D. Tendler,” conducted by Shaul Seidler-Feller (Kol Hamevaser, August 31, 2010):

My shver was uniquely sensitive to society. Despite what they write in all the books about him, my shver never failed to read the Yiddish newspaper—either the Tog in the early years or the Morgn-Zhurnal later on—cover-to-cover every single day. People publish that he would walk down the street and avert his eyes when he passed by newspaper stands. There are a thousand talmidim of his who will testify, “I bought the paper and handed it to him in the lunchroom in the yeshivah,” but it does not make a difference for some people—they do not want to hear that. Even when he was not well and the doctor insisted that he must lie down to sleep for an hour, he would go home, put on a bathrobe, and smuggle a newspaper into the bedroom so that his wife would not see it. He sat there reading the whole time, rather than sleeping. I used to ask him, “Why do you read this chazeray (junk)?” He would respond to me, “Dos iz mayn vinde”—this is my window [to the world]. He understood society and his piskei Halachah show that. He used to say, “People think that because I’m aware of society, I became a meikel (lenient decisor). What do they want me to do—paskn incorrectly? I’m not a meikel—I paskn the way it has to be. The Halachah takes into account societal factors.” This willingness to be exposed to society made his teshuvos more meaningful and more acceptable.

R. Tendler’s account would appear to be supported by R. Feinstein’s own words. Toward the end of Iggerot Moshe, Y.D., vol. 1, #172, he writes that he does not go out of his way to see if the Tetragrammaton was printed in the newspaper before discarding it. And in the unlikely event that he would find one of the seven primary holy names of God in the paper, he would cut it out and set is aside for burial. This ruling presupposed that he was reading at least some kind of newspaper on a regular enough basis.

Reflecting on the Iggerot

While R. Feinstein’s responsum permitting reading the news on Shabbat does not prove that he personally spent his time doing so, it does chip away at the narrative that he was categorically opposed to engaging with such content. As we proposed in our previous column on secular education, perhaps much of the confusion comes from a conflation between secular knowledge with secular values. Many point to how he prefaced his defense on artificial insemination as incontrovertible proof that he never opened a secular book (Iggerot Moshe, E.H., vol. 2, #11): “My entire outlook is based on knowledge of Torah without any mixture of external ideas.” Indeed, R. Shmuel Birnbaum eulogized R. Feinstein that “he surrendered himself completely to that which is written in the Torah of God, the four sections of the Shulhan Arukh, eliminating any personal bias in how to rule” (Meged Givot Olam, vol. 2, p. 31). However, surrendering to the will and outlook of the Torah need not be at odds with being informed by knowledge of the broader world. As R. Tendler contended, his father-in-law’s insistence to remain apprised of the world around him served as an asset in his ability to issue halakhic guidance for the public.

While the question of whether R. Feinstein read newspapers may strike some of us as an inconsequential matter, it serves as a significant flashpoint demonstrating how his posterity and disciples differed in how they framed his legacy to the masses.

Endnote: See also R. Dr. Harel Gordin’s Hanhaga Hilkhatit be-Olam Mishntane (p. 59, fn. 68) for a brief treatment of this topic.

Moshe Kurtz serves as the Assistant Rabbi of Agudath Sholom in Stamford, CT, is the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later

Prepare ahead for our next column on animal cruelty in halakha (Febraury 13): Iggerot Moshe, E.H., vol. 4, #92