Unpacking the Iggerot: Series Introduction

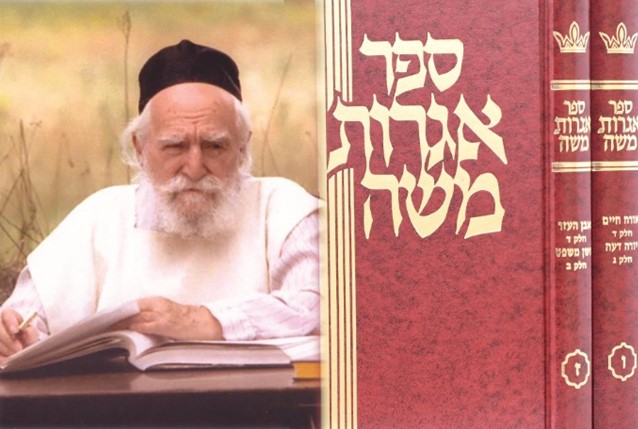

In this new TraditionOnline series, “Unpacking the Iggerot,” we will be exploring the responsa of R. Moshe Feinstein zt”l, widely regarded as the posek ha-dor, the leading halakhic decisor of the 20th century, certainly within the American Jewish experience and throughout the Jewish world as well.

In this new TraditionOnline series, “Unpacking the Iggerot,” we will be exploring the responsa of R. Moshe Feinstein zt”l, widely regarded as the posek ha-dor, the leading halakhic decisor of the 20th century, certainly within the American Jewish experience and throughout the Jewish world as well.

See an index of all the entires in this series.

By analyzing the halakhic writings of R. Feinstein, our goal will not just be to appreciate his immense scholarship, but to provide a window into the overarching halakhic, philosophical, and policy considerations that poskim consider when addressing the pressing issues of their day.

[Listen to Moshe Kurtz discuss this series on the Tradition Podcast.]

R. Moshe Feinstein was born March 3, 1895 in Uzda, Belarus. He served as the rabbi of Lyuban for sixteen years and subsequently moved with his family to New York City in January 1937, where he lived until his death on March 23, 1986, at the age of 91. Over the course of his life in America, he served as the Rosh Yeshiva of Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem, presided as president of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada, and chaired the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudath Israel of America. Aside from other important works of commentary, his monumental Responsa Iggerot Moshe began appearing in 1959, and now contains 9 volumes (the last two volumes appeared posthumously).

[We will link to a digital copy of each week’s Iggeret under discussion in the hope that readers will make the effort to study the original response in its original. The first 8 (or 9) volumes of Iggerot Moshe are available at HebrewBooks.org, although adding this set of sefarim to your home library is highly recommended.]

To understand his uniqueness it is useful to turn to his introduction to Iggerot Moshe. A common thread that emerges from his writings can be adequately expressed by the verse “Now Moses was a very humble man, more so than any other man on earth” (Numbers 12:3). In explaining his motives for publishing his responsa, R. Feinstein reflects:

And that [publishing] this may also produce pride for my father and master the Gaon zt”l who said about me that he hoped, and was basically certain, that the amount of people coming to seek the oral and written word of God from me would continue to grow – and with the help of God, I would answer them in accordance with Jewish Law.

There is a unique human quality to the admission that gaining his father’s pride was a significant motivating factor. I believe that the humanity of R. Feinstein’s personality is something that we will appreciate as we explore how he handled various questions and quandaries posed to him.

Throughout his introduction, he reiterates that he has no interest in imposing his psak on other people, and that his only agenda was simply to answer the inquirer about their unique situation—inferring from Berakhot (4a) that one who is capable of answering a halakhic inquiry may not decline to address the question brought before him. In fact, he explicitly requests that those who are thoroughly conversant in halakhic literature should read and determine for themselves whether they are persuaded by his analysis – the same way he critically analyzed those who came before him.

R. Feinstein was vehemently opposed to reducing the Iggerot Moshe to its bottom line and leaving it ossified as settled law for others to blindly follow. This philosophy led him to oppose disseminating the conclusions of his responsa for the public while omitting his sources and considerations:

I have heard that someone is about to publish an English translation of some of the responsa conclusions from my Sefer Iggerot Moshe. It is forbidden to do so even if the translation is accurate. In our time no one is permitted to issue final rulings on halakhic issues without also publishing his sources and his halakhic reasoning. Some have asked my permission to do so and I have refused their requests. Some will surely translate inaccurately or, what is worse, write in my name that which will cause others to err. Even if they were to translate the entire responsum, and not just the final conclusion, much damage can result from allowing people untrained in the intricacies of halakhic precedent to use my responsa as case histories, [and then] apply [my decision] to other cases which they deem to be identical but which really are not. Therefore, I protest with all my might against such translations (Y.D., vol. 3, #91).

The following year, 1983, R. Feinstein elaborated further:

First let me explain the short responsum published in Iggerot Moshe, Y.D., vol. 3, #91. I had not intended to include it in my sefer; [my intention in writing it] was only to voice my objection to the publication of my conclusions without providing my references or reasoning. I know how deficient I am in knowledge of the entire Talmud, both the Bavli and the Yerushalmi, and the novella and commentaries of the poskim and Talmudic scholars, some of which I have not even seen. In my writings, I rely on [the fact] that I have analyzed the halakhic sources to the best of my ability, for that is the essential requirement for issuing halakhic rulings, as I wrote in my preface to the first volume of the Iggerot. Since I have recorded my reasoning and my sources, I view my responsa as lectures which all may review for themselves, choosing to accept my position or reject it. This was also the approach of R. Akiva Eiger. I understand very well that some will not study my responsa and will merely rely on my conclusions. However, since [everyone] has the opportunity to undertake such study when time permits, it is not my fault if [anyone] fails to do so.

The recorded reasoning is the essence of a responsum. After the close of the Talmud, we cannot innovate reasons not contained therein; rather, we must try to understand the Talmud’s reasons. Approaches to the study of Talmudic reasoning on a specific topic may vary. This is why there are many controversies between Rambam and Tosafists and between Shakh and Taz, Magen Avraham and Sema, Helkat Mehokek and Beit Shmuel, and others. Therefore, it is not appropriate to write a definitive halakhic text containing final decisions without sharing one’s reasoning with the readers. My main reason for writing the above is to explain my objection to translating just the final conclusions of my responsa (Y.D., vol. 4, #38).

When my rebbe, Rabbi Dr. Moshe Dovid Tendler zt”l, translated and published various medical responsa of his father-in-law, R. Feinstein, he was therefore naturally concerned about his undertaking. He even deepens R. Feinstein’s original rationale for hesitancy:

Exposure to this technical literature without the proper background may lead to terrible errors, misinterpretations, and misapplications, as untrained readers allow themselves to compare and contrast what seem to be similar cases to the untutored eye. Reasoning by analogy requires a thorough understanding of the halachic process, an understanding which the posek has mastered after a lifetime of assiduous study [see introduction to Responsa of Rav Moshe Feinstein: Translation and Commentary (Ktav, 1996); thanks to R. Shimshon Nadel for bringing this passage to my attention].

R. Feinstein’s fear was that the uninformed reader would extrapolate a narrow dispensation in one scenario to permit something that he had not intended. My hope is that this series will not elicit such a concern: First, we will be summarizing the sources and considerations, not just the bottom line. Secondly, and more importantly, I must emphasize that anything written in this series should not be taken as halakha le-ma’aseh— please do not attempt to draw any practical halakhic conclusions from these essays.

As mentioned, R. Feinstein welcomed informed disagreement with open arms. Indeed, during his lifetime he ruled on a host of halachic controversies such as the Manhattan Eruv and Artificial Insemination which resulted in harsh criticism from many of his contemporaries. Presumably, most Torah scholars who disagreed with R. Feinstein were acting in the spirit of milhamta shel Torah. However, some of R. Feinstein’s detractors unequivocally went a step too far.

Regrettably one of the necessary resources for the study of Iggerot Moshe is the Sefer Ma’aneh Le-Iggerot, published in 1974 by R. Yomtov Schwartz, a Satmar rabbi in Queens, NY, with a stated goal to debunk any dispensations that R. Feinstein issued “to lead the public astray.” The book is a sustained hit-piece not only on Iggerot Moshe, but on R. Feinstein himself. Response to the affront to a figure of such high esteem as R. Feinstein reportedly caused a ban and recall of much of the book’s inventory, rendering it somewhat hard to locate today. R. Ovadia Yosef first cites this work in Responsa Yabia Omer (vol. 6, O.H. #48) and parenthetically notes that its author “should have conducted himself respectfully vis-a-vis the Gaon [R. Moshe Feinstein].” Nonetheless, this did not prevent R. Yosef from referencing the work on several occasions (e.g. in vol. 9, O.H. #98 he issues a similar caveat). In accordance with R. Yosef’s approach, we will attempt to extract the worthwhile content and disregard the inappropriate formulations.

Generally, our essays will touch on broad topics, such as kavod ha-beriyot (human dignity) and hasagat gevul (competitive business practices), though we will dedicate our attention to source-material that is directly pertinent to understanding R. Feinstein’s responsum, which is our central subject of analysis. Something unique and exciting about R. Feinstein’s writings is his independence and creativity – one never reliably determine whether R. Feinstein will offer a jolting leniency, such as in the case of smoking tobacco (Y.D., vol. 2, #49) or an uncompromising polemic, like in his opposition to smoking marijuana (Y.D., vol. 3, #35).

Each essay in this series will: Summarize a noteworthy responsum from Iggerot Moshe; compare and contrast the responsa with other decisions rendered by R. Feinstein; account for scholars who contended with his reasoning; and reflect on the broader philosophical and methodological considerations that emerge from how R. Feinstein (and his ba’alei plugta) addressed the topic.

One sefer which has been exceedingly resourceful in preparing the series and deserves acknowledgment is the Petihat Ha-Iggerot by R. Yonoson Rosman (Ramot Press, 2016), who compiled sources and provided some of his own analysis on many of the most pivotal decisions rendered by R. Feinstein. Naturally, we will provide our own original sources and analysis, but this outstanding work deserves much credit as serving as the best available supplement for studying Iggerot Moshe.

On a personal note, I had the immense privilege of studying many entries in Iggerot Moshe one-on-one with Rabbi Tendler. During our sessions together he would weave in anecdotes about what made “the shver” so special. R. Tendler related that at the end of R. Feinstein’s life he expressed gratitude to God for granting him the strength to ensure that every one of his inquirers would receive a response to their question. What made R. Feinstein distinct from many of his “peers” in the yeshiva world was his accessibility. He did not suffice with only serving as a rosh yeshiva, but dedicated an exorbitant amount of time to offering guidance tailored to the specific needs of the common individual. R. Feinstein made it clear that no shayla – and no shoel – would go unanswered.

I feel that this series is a perpetuation of that mesorah I received from those sessions with R. Tendler zt”l; my prayer is that readers will develop a similar appreciation and admiration that I – and many Jews – have for the rabban shel kol benei ha-gola, HaGaon HaRav Moshe Feinstein zt”l.

Moshe Kurtz serves as the Assistant Rabbi of Agudath Sholom in Stamford, CT, is the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later podcast.