Unpacking the Iggerot: Sunrise, Sunset & Sunset

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Rabbi Feinstein’s Theory of Time is Relativity / Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 4, #62

Summarizing the Iggerot

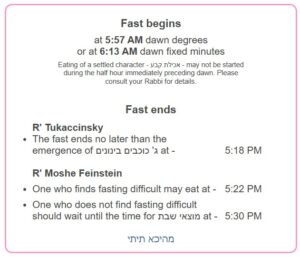

If you were to log on to MyZmanim.com to ascertain the end-time for the Fast of the 10th of Tevet (December 30, 2025) in Allentown, PA, you would be provided with the following information:

Why are there various times for when a fast day should end? What is the difference whether someone is finding it difficult? Should the end of the day not be an objective, fixed measure? And why would there be a distinction between the end of the day for a fast versus Shabbat or any other time-bound mitzva? To answer this question, and to understand R. Moshe Feinstein’s unique perspective on the topic, a very brief introduction to zmanim is in order.

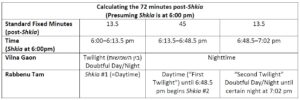

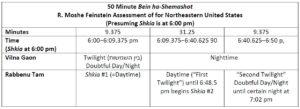

The Talmud (Shabbat 35b) informs us that nightfall occurs when there are three medium stars visible in the sky (tzeit ha-kokhavim). While this is the most iconic description of halakhic nightfall, it is a far cry from providing us with any form of precision. However, the Talmud (Shabbat 34b) also records the opinion of Rabbi Yehuda that night only begins after a period of twilight which elapses from shkiya (sunset) for the time it takes to walk three-quarters of a mil. Assuming the time it takes to walk a mil is 18 minutes, three quarters of a mil would come out to 13.5 minutes. In other words, there would only be 13.5 minutes of twilight between sunset and nightfall, a window of time whose status as day or night is questionable. This is the position attributed to the Vilna Gaon and represents the most standard approach.

However, the Talmud (Pesahim 94a) also provides a very different assessment that nightfall begins only after an entire four mil have elapsed, which would bring us to at least 72 minutes post-sunset. Rabbenu Tam reconciles the two passages in the Talmud by suggesting that after 58.5 minutes elapse a “second shkiya” begins, whereby the remaining 13.5 minutes constitute halakhic twilight, while the prior 58.5 minutes post-sunset are still actual daytime.

R. Feinstein introduces something very clever. He insists that we err on the side of caution and observe Rabbenu Tam’s four mil for the end of Shabbat, yet he modifies it based on the Vilna Gaon who posited that the times are not fixed, but latitude-dependent. “And therefore,” he observes, “here in America, in our city of New York, and in New Jersey, and all the summer places in the mountains where I have been personally—from what I have heard, most of America is like this—that after 50 minutes following sunset the entire sky is full of stars and it is dark like the middle of the night, no less than it was like in the places in Europe that we were from that it took 72 minutes or more [to reach the same degree of darkness].”

Based on this assessment, the four mil have now been constricted to 50 minutes, which means that three quarters of one mil equals slightly more than nine minutes.

This approach yields significant ramifications as it affects virtually any halakha that is contingent upon the arrival of nightfall. We will outline some of the examples that R. Feinstein notes in the responsum:

- A Jew is allowed to ask a gentile to perform prohibited labor on Shabbat during twilight. Therefore, in the case of significant need, one may rely on Rabbenu Tam until about 40 minutes past sunset to solicit a non-Jew’s assistance.

- Likewise, at the end of Shabbat, one need only wait until ten minutes after sunset to ask a non-Jew to perform melakha, as it is already nightfall according to the Vilna Gaon.

- A boy born on Shabbat will generally have a brit on Shabbat, as the mitzva of a brit mila supersedes Shabbat. However, a boy born during twilight does not receive his circumcision on Shabbat, because twilight is unresolved territory, it is possible that he is not scheduled to have his brit on Shabbat, whereby the circumcision would constitute a Biblical transgression. Yet, one could potentially employ a double-doubt: The first nine minutes after sunset are questionable day-night according the Vilna Gaon, which is a doubt due to a lack of data (metziut). And the second mitigating factor is that perhaps the halakha is in accordance with Rabbenu Tam who holds it is still daytime anyway. R. Feinstein does not like employing this line of reasoning in practice, though he states that he would not object to those who wish to rely on it.

- Hefsek Tahara: In order for a woman to begin counting the seven post-menstruation days , before immersing in a mikve, she must perform an internal check to ensure she no longer detects menstrual blood. According to R. Feinstein, a woman would only be granted a grace period of nine minutes after sunset which would still count halakhically as the day prior. Note that his minimization from 72 to 50 minutes results in the woman decreasing her 13.5 minutes of twilight for only nine minutes. This case demonstrates that R. Feinstein’s theory of zmanim carries implications not just for leniency, but stringency as well.

- Of course, we must return to the MyZmanim listing for minor fast days. Since we are dealing with, at most, a Rabbinic matter, it would be acceptable to break the fast during the twilight of Rabbenu Tam, since we may rely on the Vilna Gaon’s position that it is already then nightfall, and would at most only be questionable day/night according to Rabbenu Tam. Accordingly, one may eat after approximately 41 minutes post-sunset if they are having difficulty. However, R. Feinstein advises those not experiencing particular challenges to account for Rabbenu Tam’s stricter position of 50 minutes. This accords with the variance between 5:22pm versus 5:30pm on the MyZmanim example for the upcoming Tenth of Tevet listed above.

(There is more to the responsum in terms of analysis and even some eyebrow-raising jabs at the American rabbinate. We plan to address the latter aspect in a later column.)

Connecting the Iggerot

While our main responsum was dated to 1979, there is actually a more succinct precursor that was penned a decade earlier and subsequently printed in the first volume of Iggerot Moshe (O.H., vol. 1, #24). Notably, this is where he first asserts that the Vilna Gaon is considered batra’a, the later and final word on the matter. Nonetheless, due to the gravity of Shabbat observance, he writes “who are we to decide between these lofty mountains,” and rules that we adopt the Vilan Gaon and Rabbenu Tam stringently in both directions.

Jumping ahead to 1981, R. Feinstein writes something remarkable about the primacy, or lack thereof, of the Vilna Gaon (Y.D., vol. 4, #17:26). One might wonder, when did the members of the Vilna community end Shabbat? Certainly it would have been about 13.5 minutes after sunset in accordance with the Vilna Gaon himself? To that, R. Feinstein writes:

And even if there were many of his disciples who conducted themselves in accordance with him, they did not rule as such to the public. And the Gaon himself did not instruct this, not even to his own city of Vilna. And we know that many of the great [Torah scholars] of this world who were students of his students were stringent beyond the Gaon himself, even in matters of the time for reciting Shema and the evening prayer, and certainly for Shabbat and Holidays. Therefore, we should not end Shabbat in accordance with the Vilna Gaon’s position, but rather act strictly in accordance with Rabbenu Ram’s calculation for nightfall.

Reception of the Iggerot

Astonishingly, R. Feinstein’s own computation skills were once called into question. In Iggerot Moshe (O.H., vol. 1, #24), he responds to a letter from R. Shalom Halevi Kugelman: “Regarding that which you wrote, that the list of zmanim for the yeshiva are imprecise, [know that] it was done with great attention to detail by me personally.” He then proceeds to explain how the hours of the day are calculated and why, aside from the two yearly equinoxes, there is an asymmetry between the daylight portion of each day and the night.

Astonishingly, R. Feinstein’s own computation skills were once called into question. In Iggerot Moshe (O.H., vol. 1, #24), he responds to a letter from R. Shalom Halevi Kugelman: “Regarding that which you wrote, that the list of zmanim for the yeshiva are imprecise, [know that] it was done with great attention to detail by me personally.” He then proceeds to explain how the hours of the day are calculated and why, aside from the two yearly equinoxes, there is an asymmetry between the daylight portion of each day and the night.

The skill of calculating zmanim was not foreign to R. Feinstein at all. This was simply one of the many things that a community rabbi needed to know how to do prior to the proliferation of the Ezras Torah Luach and websites like MyZmanim. In Man Malkhi Rabbanan, p. 20, it is reported that as R. Feinstein was fleeing Lyuban for America, he wrote up a schedule for the times and holidays for the coming eighteen years as a parting gift to the community.

R. Kugelman also challenged R. Feinstein based on a report from his father who observed that on Ellis Island it took well over “an hour and a fifth” after sunset for it to become absolutely dark. R. Feinstein refutes this, citing Talmudic precedent that the Sages acknowledged there could still be some residual light even after nightfall. (While the observation was ultimately rejected, think of how remarkable it is for a Jewish immigrant at Ellis Island, having left everything behind and with an uncertain future ahead, looking out to the horizon to determine the time for halakhic nightfall!)

To appreciate R. Feinstein’s novel approach to the end-time for Shabbat, it is worth contrasting it with the Satmar Rov, R. Yoel Teitelbaum, as reported in R. Moshe Shternbuch’s Uvdot ve-Hanhagot (p. 475; see also ibid p. 481). When R. Teitelbaum was petitioned to support a demonstration against the desecration of Shabbat, he inquired as to the nature of the violations they would be protesting against. The organizer responded:

They keep their stores, restaurants and theaters open on Shabbat, rahmana litzlan. [R. Teitelbaum responded]: Why do we need to seek out transgressions of Shabbat by the secular? Behold, the Haredim are violating Shabbat publicly by ending it before the nightfall of Rabbenu Tam, which is the majority opinion of the halakhic authorities. If there will be a protest against this kind of Shabbat desecration then I will join!

And when the organizer pushed back arguing that the custom is not to follow Rabbenu Tam’s stringent time, R. Teitelbaum responded with the adage that “Minhag spelled backwards is Gehenom (Hell)—and such a custom has no standing.”

Reflecting on the Iggerot

After taking into account the vehement proponents of Rabbenu Tam, such as the aforementioned anecdote involving R. Teitelbaum, we can appreciate R. Feinstein’s contrasting position. If we recall, he also adamantly objected to concluding Shabbat early based on the Vilna Gaon, and remarkably contended that the Gaon apparently did not implement his own lenient opinion in practice. R. Feinstein concurs that in principle we must observe Shabbat in accordance with Rabbenu Tam, he just simply disagrees regarding the application. He believes that observing Rabbenu Tam in the American Northeast means waiting 50 minutes, tantamount to the 72 minutes observed in the European Northeast.

My colleague, R. Ben Keil pointed out that this is conceptually analogous to what R. Feinstein propounds in his well-known halav Yisrael responsa on unsupervised milk. He does not simply issue a dispensation to drink halav stam, a leniency that had been issued generations earlier. Rather, the novelty of his approach was the contention that milk under FDA supervision is actually halav Yisrael. Just like the 50 minutes is not an alternative to Rabbenu Tam but is identical to Rabbenu Tam’s 72 minutes at other locales. R. Feinstein, in both instances, reinterpreted the stringent position rather than dismissing it.

While R. Feinstein provides a compelling argument, rooted in a mastery of the original sources, he was also willing to concede the rare occasions that the Talmudic canon did not provide clear guidance. When asked how to navigate zmanim on airplane flights he writes that “it is difficult to reply to this matter, for there are no actual sources from the words of our Sages. Therefore we must analyze this matter based on [our own] logical reasoning” (O.H., vol. 3, #96).

He expressed that he was not concerned vis-a-vis Shabbat as “those who are God-fearing would not travel on an airplane on Shabbat.” As for the time of prayer, he surmised it would simply shift based on one’s current location. The same principle would also be true when traveling on a fast day, as R. Aharon Felder summarizes:

One who began fasting at one location and travelled to another location during that day, ends fasting at the same time as the people in the latter location even if the traveler’s fasting time is increased or reduced as a result of the trip (Moadei Yeshurun, p. 109).

Remarkably, MyZmanim has introduced a function in which one need only enter a flight number to be provided with a calculation of their personalized in-flight zmanim, and this data is available in midair and in real time from the seat screen on all El Al flights.

This general topic serves as both an inspiring and humbling example of the ability and limits of humanity to quantify all aspects of our lives. Even from this brief treatment, we can already sense that there is more to the equation than objective, mathematical calculations alone.

Endnote: For more on R. Feinstein’s rulings about air travel, see Iggerot Moshe (O.H., vol. 2, #59), in which he argues that one should recite the blessing of HaGomel to thank God for safe passage, just as one would do after a sea journey. Also, see our article “Pure Passengers & Complicated Cargo” about whether a kohen may fly on a plane that is also transporting a corpse. In “Time Flies: A Guide To Time-Related Halachos When Flying,” the Star-K provides succinct and practical guidance as to how to manage zmanim challenges during air travel.

For more on the calculation of zmanim, see Iggerot Moshe (Y.D., vol. 4, #48:4) in which he reiterates his position on accounting for the opinion of Rabbenu Tam. R. Aharon Felder reports that R. Feinstein consistently applied his theory of zmanim to permit a divorce document to be given until 50 minutes after sunset (Reshumei Aharon, vol. 1, p. 79).

See also Iggerot Moshe (O.H., vol. 2, #60) regarding what should be done in a case that the congregation opts to pray Maariv prior to the (ideal) time. And for another calculation related topic, see Iggerot Moshe (O.H., vol. 1, #136) in which R. Feinstein addresses the context dependent assessments of the measurement of an amah.

It is notable that our primary responsum was addressed to Rabbi Dr. Moshe D. Tendler on 25 Shevat 5739. While on Rosh Hodesh Adar 5739, just a few months apart, he wrote to the very same inquirer about daylight savings time, as we addressed in our article on “Tefillin and Daylight Savings Time.” I suspect that R. Tendler posed several questions to his father-in-law, some related to zmanim, and the responses to the various questions were sent over the course of a few months. Perhaps R. Tendler was attempting to prompt his father-in-law to provide his general theory of zmanim. While this is speculative, with both responsa sharing similar topics, with proximity of date, and the very same inquirer would support such an inference.

Moshe Kurtz is the rabbi of Cong. Sons of Israel in Allentown, PA, the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later podcast.