WOODCUT MIDRASH: Sihon and Og – The Last of the Giants

WOODCUT MIDRASH: Sihon and Og – The Last of the Giants

Mordechai Beck

Sihon would not permit Israel to cross his border and brought out all his people and went out to meet Israel in the desert and Israel smote them and took the land (Numbers 21:23).

They [the Children of Israel] turned and they went up by way of the Bashan and Og, king of Bashan came to meet them – he and all his people – at Edrei (Numbers 21:33).

After he had defeated Sihon, king of the Emorites, who lived in Heshbon, and Og, king of Bashan, who lived in Ashtarot and in Edrei (Deuteronomy 1:4).

Sihon, king of the Emorites, for His love is forever / and Og, king of Bashan, for His love is forever (Psalms 136: 19-20).

According to Rashi – basing himself on Sifrei – the opening lines of the Book of Deuteronomy are mere hints at sins committed by the Children of Israel as they crossed the deserts from Egypt. The

names mentioned here – Arava, Suf, Paran, Tofel, Lavan Hazerot, Di-Zahav – are suggestive of particular events that they underwent. Arava, for example, meaning “plain” is meant to remind them of their idolatrous behavior in the plains of Moab; Paran is a reminder of the sin of the spies; Hazerot – the rebellion of Korah, etc. The reason for this covert style of the text is to save the Israelites from embarrassment – especially since these were the sins of their fathers and not of the current generation.

Nevertheless in the fourth verse explicit names are mentioned – namely Sihon, king of Emor, and Og, king of Bashan. Enemy leaders who attempted to prevent the Israelites from crossing in to the Promised Land – and thus are to be eliminated. But surely, recalling explicitly victories over these kings goes against another religious value – the injunction against rejoicing over the downfall of our enemies. Why were these names also not given to us in hints by recalling the places in which these victories came, Emor and Heshbon, or Bashan and Ashtarot Edrei? Why wouldn’t these have been enough? What was so special about these two kings to mention them specifically?

Moreover these kings are named not just at this opening but also numerous times within the weekly portion. The name Sihon is mentioned seven more times, and Og four times. What is so significant in these two characters?

We have previously encountered Sihon:

Israel sent messengers to Sihon King of Emor saying: Allow us to cross your territory, we will not turn into your fields or your vineyards, we will not drink from your wells, but will go by the Way of the Kings, until we have crossed your border. But Sihon would not permit Israel to cross his border and brought out all his people and went out to meet Israel in the desert and Israel smote them and took the land (Numbers 21:21)

This conquest includes the city of Heshbon, since, “Heshbon was the city of Sihon king of Emor who had fought the first king of Moab and taken all his land up to Arnon” (Numbers 21: 21-27). The Midrash elaborates on Sihon’s victories – saying that he took over the entire land of Canaan and extracted tribute from them all: this is the “heshbon” (lit. account) that Sihon worried over; Canaan was his pot of gold (di-zahab). You’re going to come in and not take over my nest egg? Are you crazy? What do you take me for? (Bamidbar Rabba 19:29-30)

And thus (continues the midrash) just as Sihon took over Moab, so did God take over the rich pickings of Sihon (heshbon) – since “one who steals from a thief is innocent of robbery.”

Og also appears in the same chapter of Numbers: “And they [the Children of Israel] turned and they went up by way of the Bashan, and Og king of Bashan came to meet them – he and all his people – at Edrei… And God said to Moses ‘Don’t be afraid of him, because I have given him into your hands just as you did to Sihon king of Emor” (21:33).

According to Pirkei deRebbi Eliezer (23), Og is the last of the giants that flourished before the Flood and survived the Flood thanks to the generosity of Noah – in so doing he swore eternal fealty to him. In another source, he is the servant Eliezer, part of a gift given by Nimrod to Abram after the latter has succeeded in emerging unscathed from the furnace into which the wicked king had thrust him (Pirkei deRebbi Eliezer 15; Targum Yonatan 14:13). As a reward for his life-long loyalty to Abraham (Zohar 3:184, where he is the one who circumcises his master), God transforms him into Og, king of Bashan.

There is also a downside to this giant. He lusts after Sara, and makes calculations about how he will take her upon Abraham’s death (Bereshit Rabba 42:8). Maybe his powerful sexual urges come from the fact that his seed produces 36 liters of liquid (Sofrim 21:9) enough to populate a decent size city. Without going into all the other legends accorded to Og, suffice to say that by the time Moses confronts him he has put on some years. “I am a mere 120 years old,” says Moses, while Og is over 500 years old – surely that means he has some special merit (Bamidbar Rabba 19:32). In another source, this is the reason why Moses was fearful of Og as opposed to Sihon: he surely had merit points still from his time with Abraham (Nidda 61a) especially as the one who circumcised the ancestor of all the Jewish people. This is not to suggest that Sihon was somehow inferior to Og.

According to the Talmud, Og and Sihon were brothers – the sons of Ahia who was himself the son of Shamhazai, which puts their origin back in the stone age – or at least in the fabled time when angels and people of flesh and blood mixed freely with each other. Both were of giant proportions – both are depicted sitting on the walls of their respective capital cities with their legs reaching down to the ground. The appendix of Midrash Tanhuma (Devarim) states “Sihon and Og were tougher than Pharaoh and his armies.” Despite this, they were both arrogant and despite the fact that they were neighbors, neither would lift a finger to help the other.

What does this all mean? Perhaps it can be understood in juxtaposition with the verses Moses speaks shortly after the opening: “God spoke to us at Horeb and said… Behold I have given you the land – come and possess the land which was sworn to your ancestors – Abraham, Isaac and Jacob – to give it to them and their descendants after them” (Deuteronomy 1:8). Rashi explains that this is a proof text: I didn’t tell you fables, look with your own eyes: the land is yours to take! And if it hadn’t been for the spy scandal you could have had it without weapons.”

Which is to say that Moses offers a commentary on what had been and a vision of what could be in the future. Forget Og and Sihon – they may look scary and awesome – but we’ve beaten them. We can beat them again. The period of myth is past. Eretz Canaan is the reality with which you have to deal. This is not a promise of conquering the world but just one, modest-sized country. Remember the covenant I made with your ancestors – here you are just a step away from fulfilling that promise.

There is, perhaps, something deeper here, in the figures of Og and Sihon, which Moses is trying to convey to the people about to enter the promised land. Og and Sihon are giants, not only physically but also in terms of their material achievements. According to the sources we have quoted above they are deeply attached to money and power. These are the basis of their lives. Moses in specifying them by name wishes to draw the people’s attention to this side of the equation. Their twisted logic has placed their egos above that of sensitivity towards their fellow human beings. They are so involved in self-promotion and self-regard that they have no room to help each other, even in times of want. This is the opposite of what Moses wants the people to be in the land of Canaan.

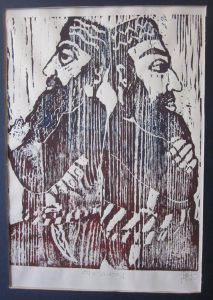

The woodcut shows the two brothers, Og and Sihon, sitting with their backs towards each other, daggers stuck in their belts, looking aggressively at the world around them. They are egos personified. Nothing stands in the way of their own concerns. Their whole demeanor suggests that they are on the lookout for number one. This is not what Moses is demanding of the Children of Israel once inside the Promised Land.

Mordechai Beck is an artist and writer residing in Jerusalem. He is seeking a publisher for his collection of essays on “marginal” Biblical figures with prints.

[Published on July 21, 2020]