The BEST: Leaves of Grass

The BEST: Leaves of Grass

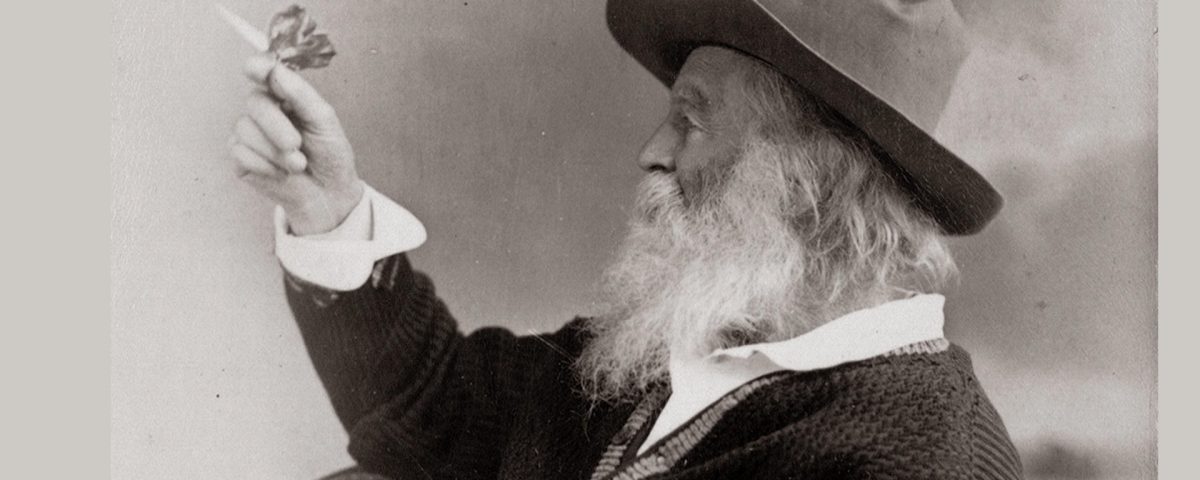

by Walt Whitman

Reviewed by Sarah Rindner

Summary: Leaves of Grass is a sprawling collection of poems written by the 19th century American poet Walt Whitman. He spent much of his life revising and working on it – the final product includes more than 400 poems. In them, Whitman explores his own unique voice and his relation to the people around him, the literary past, the still new country of the United States, and the universe. He mentions God frequently, but he is not a conventional believer. He seeks to get to “the origin of all poems,” a deeper mode of consciousness that precedes our culture and our beliefs, which also celebrates the very same culture and beliefs.

Why this is The Best: Whitman’s exploration of human sensuality and his irreverence for traditional Christian dogma generated controversy when Leaves of Grass was first published. They certainly could still cause discomfort to a religious person reading them today. Yet the book has an “original energy” that is undeniable, and offers a model of how to radically innovate while still building on and channeling a tradition that stretches far back.

Perhaps Rav Aharon Lichtenstein chose to channel Whitman with the name Leaves of Faith for his collection of moral essays, based on more than the title’s pithy cadence. Both books epitomize the effort to contribute something exciting and new to a traditional canon while still maintaining deep respect and affection for the tradition you are building upon.

While not a person of “traditional” faith, Whitman is a moral writer. His poetry exudes concern for others and the desire to alleviate their burdens. Indeed Whitman was a “good person” in many respects – a moderate abolitionist who tended wounded Civil War soldiers as a nurse.

It may be impossible to really summarize Leaves of Grass, but I want to share a few snippets from the volume’s most well-known section, “Song of Myself,” with some commentary:

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

Whitman was a great poet, but his sense of the power of the poet is one in which the individual ego meshes with the collective. When Whitman talks about his “self” it is something much broader than his literal self, it is more like a triangle between himself, God, and his readers. To me, this brings to mind the idea of malkhut, the lowest of the kabbalistic sefirot, which is an emergent property from within a collective (as described by R. Moshe Miller in his Rising Moon: Unravelling the Book of Ruth). He uses his individual voice to express the spirit of the still nascent Unites States of America, and in doing so also suggests a model of how something composed of many parts can be one.

Creeds and schools in abeyance,

Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten,

I harbor for good or bad, I permit to speak at every hazard,

Nature without check with original energy.

Whitman, in the spirit of the fresh and unlearned American continent he is writing for, chooses to forego the classical allusions that other epic poems contain. He is not one for stuffy titles or elitism, but he respects formal schools of learning – “sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten.” He does not cavalierly discard tradition but seeks to express it in a way that is organic and natural. To me, this is what Jewish faith should be as well – rather than agonizingly struggle with or project, it naturally flows out of us. As for “nature without check,” I’m not quite sure that it’s a Jewish value per se, but I’m not quite sure Whitman believes that it’s a fully attainable goal either.

I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the beginning and the end,

But I do not talk of the beginning or the end.

There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now,

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now.

There’s a stereotype of religious life that it is obsessed with life after death, and perhaps also the creation stories that preceded it. Whitman is not interested in the beginning or end, and he is right. For Whitman, and, I think, for us all, the correct place to focus is the present: on our obligations, our blessings, and our opportunities to grow in the here and now. As the Psalmist reminds us, and which is true every day, “This is the day that God made, we shall exult and rejoice in it” (Psalms 118:24).

As for the grass metaphor of the title, I love how Whitman plays with this very simple unassuming plant, giving it different associations and meanings throughout the poem, and also undermining his own authority to opine:

A child said What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands;

How could I answer the child? I do not know what it is any more than he.

But one of the casual explanations that he suggests is a subtle, potent encapsulation of how a religious seeker might find meaning in nature:

… I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,

A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropt,

Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may see and remark, and say Whose?

I confess that I feel similarly about a beautiful poem. Even if the poet does not share my beliefs, when I encounter a gifted writer who can channel words in a way that touches my soul, I see God’s name somewhere in the corners as well.

Sarah Rindner is a writer and educator who recently made Aliyah to Israel. Her work regularly appears in Mosaic magazine, Jewish Review of Books, and other publications.

Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.

[Published on October 22, 2020]