The BEST: Lincoln’s Second Inaugural

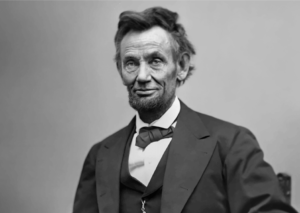

Summary: March 4, 1865, began with torrents of rain and gale winds. Photos from that day show crowds in Washington, D.C., gathered in lake-sized puddles. As Abraham Lincoln began delivering his Second Inaugural Address, the rain stopped and the clouds dispersed. With the Union’s impending victory in the Civil War only weeks away, Lincoln was expected to deliver a triumphalist speech. But Lincoln did not congratulate himself, nor did he celebrate in any way. He did not speak about himself, at all.

Instead, the speech, which Fredrick Douglas praised as a “sacred effort,” is a deep meditation on the cause of the Civil War from a theological perspective. Lincoln saw the war as divine retribution for the sin of slavery. But he did not place the blame exclusively on the South; on the contrary, he attributed blame to the North as well, “that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offence came.”

While the second shortest inaugural address in American history, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural is the most profound, revealing him as a religious thinker of the first caliber. His resigned theology sought to brace the American people to the task of rebuilding a united nation by enshrining a policy of pragmatic accommodation in place of doctrinaire vengeance.

Why this is The BEST: The Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural flank Lincoln’s sculpture in the Lincoln Memorial. Shortly after delivering it, Lincoln wrote to Thurlow Weed, a New York newspaperman and Republican party official, that he expected the speech to “wear as well as — perhaps better than — any thing I have produced.”

Historian Ronald C. White in his Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural calls attention to Lincoln’s use of inclusionary language (61):

Lincoln’s central, overarching strategy was to emphasize common actions and emotions. In this [second] paragraph, he used “all” and “both” to be inclusive of North and South. Lincoln was here laying the groundwork for a theme that he would develop more dynamically in paragraphs three and four of his address. Notice the subjects and adjectives in three of the five sentences in the second paragraph:

Sentence one: “All thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war.”

Sentence two: “All dreaded it – all sought to avert it.”

Sentence four: “Both parties deprecated war.”

These rhetorical devices allowed Lincoln to ask “his audience to think with him about the cause and meaning of the war,” not as warring partisans but as weary participants (59).

Earlier in life, Lincoln had been a religious scoffer, but he had now grown into a more mature and reflective religious thinker. Lincoln communicates knowledge of the Bible and humility, “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged.” In fact, the speech reflects an existential humility. Lincoln maintained that the divine will is unknowable, “The Almighty has his own purposes.” These themes are apparent, as well, in Lincoln’s posthumously discovered note known as the “Meditation on the Divine Will:”

In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be, wrong. God cannot be for and against the same thing at the same time.

However, submission to inscrutable providence is more fully developed in the Second Inaugural.

Lincoln concludes with a vision of Reconstruction which is infused with his generosity of spirit, “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.” In contrast to the Radical Republicans, Lincoln took a more liberal approach attitude toward readmitting Southern States into the Union. Tragically, he was never able to implement this vision. One photo from that rainy day shows John Wilkes Booth standing in the galleries behind Lincoln. Only five weeks later, Booth shot and killed the President. In doing so he deprived the nation of its greatest statesman, its greatest orator, and its greatest moral paragon.

Menachem Genack, a TRADITION editorial board member, is the CEO of the Orthodox Union Kosher Division and rabbi of Congregation Shomrei Emunah in Englewood, NJ.

Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.