Alasdair MacIntyre: Reviving Tradition

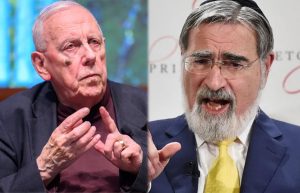

In the early days of the internet, before the almighty algorithm anointed social media as humanity’s ubiquitous source for news, entertainment, and even friendship, material both serious and satirical would oftentimes find its way into one’s inbox, having been forwarded by an individual to his or her list of extended comrades in (conceptual) arms. An early example that I recall receiving, and that Google has just shown me still exists in varying forms, was a document that addressed how Jewish commentators would deal with the question “Why did the Chicken cross the road?” A measure of the type of content therein can be gleaned from an excerpt from “Rashi’s” comment – “poulet be-la’az.” For our purposes, the most significant comment was that assigned to Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks which, paraphrasing from memory, went something like this: “In order to answer this question, it is essential that one read Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue.” This reflected, albeit in a comedic context, the genuine esteem in which R. Sacks held the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, who passed away on May 21.

In the early days of the internet, before the almighty algorithm anointed social media as humanity’s ubiquitous source for news, entertainment, and even friendship, material both serious and satirical would oftentimes find its way into one’s inbox, having been forwarded by an individual to his or her list of extended comrades in (conceptual) arms. An early example that I recall receiving, and that Google has just shown me still exists in varying forms, was a document that addressed how Jewish commentators would deal with the question “Why did the Chicken cross the road?” A measure of the type of content therein can be gleaned from an excerpt from “Rashi’s” comment – “poulet be-la’az.” For our purposes, the most significant comment was that assigned to Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks which, paraphrasing from memory, went something like this: “In order to answer this question, it is essential that one read Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue.” This reflected, albeit in a comedic context, the genuine esteem in which R. Sacks held the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, who passed away on May 21.

Alasdair MacIntyre was born in Glasgow in 1929, though he was brought up in London, to where the family moved in 1930. He graduated with a degree in Classics from Queen Mary College, London, in 1949, and followed that with an M.A. from Manchester University in 1951, during a bygone era when one could have a storied academic career without a doctorate—MacIntyre is reported to have taken great pride in being self-educated beyond his M.A. His academic career took him from teaching philosophy of religion in Manchester, to further UK posts including in Leeds and Oxford, before moving to the United States, initially as professor of history of ideas at Brandeis before once more taking up numerous professorial posts at Boston, Vanderbilt, Duke, and ultimately Notre Dame.

MacIntyre’s literal nomadism was paralleled by a roaming intellectual journey. Starting out as both a (Protestant) Christian and a member of the Communist party in London, his first book Marxism: An Interpretation (1953), as well as the later Marxism and Christianity (1968), explored the complex relationship between the two, arguing that Marxism was in fact “far more Biblical than Hegel” particularly in “seeing the proletariat, the poor … in the parable of the sheep and the goats, as those who bear the marks of redemption.”[1] There was later a dalliance with atheism but he would ultimately convert to Catholicism in the 1980s and remain a Catholic until his passing. His primary philosophical inspirations at this point included the virtue ethics of Aristotle and the Thomistic tradition more generally, though notwithstanding his break with Marxism, he would continue to critique liberal capitalism and maintain a socialist’s solidarity with “the workers” and trade unions into his advanced years.

At this point, readers might be wondering why TRADITION would commission a piece on a Marxist Protestant turned Catholic with an ongoing penchant for elements of socialism. So it is here that we turn to his classic if unofficial “trilogy” that began in 1981 with After Virtue, continuing with Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988), and Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (1990), where MacIntyre would develop his penetrating critique of modern moral philosophy and the liberal political philosophy of John Rawls.

For MacIntyre, morality had ceased to make sense in the age of Enlightenment for reasons that I can do no better than to quote my colleague R. Dr. Michael Harris (also writing for TRADITION):

MacIntyre argues that in our culture, important moral disagreements seem irresolvable. This is because the parties deploy incommensurable moral assertions, which, removed from their original theoretical contexts, amount to little more than the expression of personal attitudes. This situation has come about largely because of the failure of Enlightenment philosophers to achieve their goal of establishing a secular morality to which any rational person would need to assent.

Secular moral theories that had emerged out of the Enlightenment had been an abject failure according to MacIntyre, for whom there simply is no such thing as a universally valid ethic to which everyone must assent by virtue of their rationality. He writes:

There is no place for appeals to a practical rationality-as-such or a justice-as-such to which all rational persons would by their very rationality be compelled to give their allegiance. There is only the practical-rationality-of this-or-that-tradition and the justice-of-this-or-that-tradition.[2]

Thus, for MacIntyre, moral claims can only make sense in the context of a tradition.

The Enlightenment claims that tradition is a vestige of ancestral superstition and thus opposed to reason; for MacIntyre, on the other hand, traditions are in fact the only context within which practical reasoning makes sense. This revival of the idea of tradition as philosophically respectable obviously chimes with people of faith, and was coopted by Jonathan Sacks in his early writings, with particular reference to MacIntyre’s claim that “[a] living tradition … is an historically extended, socially embodied argument, and an argument precisely in part about the goods which constitute that tradition.”[3] There is, of course, no better illustration of this concept of tradition than the Jewish tradition of debate—a leitmotif of rabbinic literature.

But MacIntyre’s critique of contemporary morality went deeper than this. For him, the erroneous idea of a shared form of abstract universal practical rationality was rooted in a similarly misguided liberal conception of the self, according to which the self can be defined in isolation from its value commitments, “prior to and independent of purposes and ends.” [4] The self, on this view, is a featureless and therefore—the claim goes—unbiased and purely rational locus of choice, an atomistic unencumbered “chooser.” This is what allows for the modern account of the moral agent as one who, in making choices is “able to stand back from any and every situation in which one is involved, from any and every characteristic that one may possess, and to pass judgement on it from a purely universal and abstract point of view that is detached from all social particularity.”[5]

For MacIntyre, such criterion-less choices, unencumbered by any sense of personal identity, are arbitrary. Rational choice is based on reasons, and some reasons are better than others precisely because of the traditions in which we find ourselves, which provide those choices with a rational context. Furthermore, these traditions are themselves embedded within broader narrative structures that provide communities with identities. For MacIntyre, we “enter human society … with one or more imputed characters—roles into which we have been drafted—and we have to learn what they are in order to be able to understand how others respond to us and how our responses are to be construed.”[6]

This communitarian picture of the self ought once again to sound familiar to Jewish readers, for whom the idea of being born into obligations that are not of our choosing and into which we have been “drafted” is second nature. Or, as Jonathan Sacks puts it: “A Jew is a Jew by virtue of birth [and] this fact carries with it certain duties and obligations…. Jews do not choose the commands by which they are bound.”[7] We acquire obligations that are embedded within narratives that establish our communal—or for Jews even national—identity and we continue to develop these identities within an ongoing tradition of debate.

For R. Sacks then, though hopefully there is enough in the brief summary above to recognize this oneself, following their exile at the hands of a contemporary philosophy that had long subjected them to ridicule, MacIntyre managed to place ideas which had for centuries been part and parcel of Judaism back on the philosophical map. MacIntyre himself acknowledged Sacks’ use of his critique of modernity, while also noting that R. Sacks had “made an original and insightful use of that account in finding application for it to the particularities of the history of encounters of Judaism with modernity.”[8] We see then, that in time, the esteem in which MacIntyre was held by Sacks was reciprocated. Indeed, in his contribution to Radical Responsibility, a volume of essays that I was honored to co-edit in tribute to Rabbi Sacks on the occasion of his retiring as Chief Rabbi of The United Kingdom and the Commonwealth, MacIntyre wrote that R. Sacks was “one of the most notable teachers of our time” not only for his own Jewish community but also “to the wider public of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth.”[9]

MacIntyre, along with Charles Taylor and Michael Walzer, was among the most notable philosophers to appear in that volume. While our correspondence during the production of Radical Responsibility would hardly justify claims to having had a personal relationship, he was the first to submit his contribution—and well before the deadline to boot—which any editor will testify is not the usual course of events. If anyone could have asked for (and expected) an extension, or played the academic equivalent of a “diva” it would have been Alasdair MacIntyre. Accounts indicate that he could certainly be a feisty interlocutor, and there are plenty of examples of his ability to deliver a withering philosophical put-down. From personal experience though, his commitment to the project and graceful correspondence throughout left us editors with nothing but admiration. Indeed, when one co-editor, Michael Harris, was at Notre Dame in 2014 and asked on very short notice if he could drop by MacIntyre’s office to say hello, the moment he walked in MacIntyre immediately asked “How is your community in Hampstead?” reflecting either a very good memory from correspondence with an editor or a quick Google search (!), but either way, the mark of a mensch.

The MacIntyre of my (extremely limited) personal acquaintance was a pleasure to work with; the MacIntyre of my (more extensive) philosophical acquaintance was a significant influence on my early work. Thus, to conclude by returning to his own assessment of R. Sacks: “What he has said and written on a remarkable range of topics deserves careful and attentive listening and reading by both his audiences, by reason of his insights and analytical powers, both as a rabbi and as philosopher.”[10] But for the final clause, R. Sacks would likely have said the same of MacIntyre, which is reason enough for us to note his passing and encourage readers to engage with his writings if only from After Virtue onwards, though his writings throughout his career were a model of clarity and never less than interesting.

Daniel Rynhold is the Dr. Mordecai D. Katz Dean at the Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies.

[1] Alasdair MacIntyre, Marxism: An Interpretation (SCM Press, 1953), 57.

[2] Alasdair MacIntyre, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (Duckworth, 1988), 346.

[3] Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue (Duckworth, 1981), 222.

[4] Michael Sandel, “The Procedural Republic and the Unencumbered Self,” in Communitarianism and Individualism, eds. Shlomo Avineri and Avner de-Shalit (Oxford University Press, 1992), 18.

[5] MacIntyre, After Virtue, 31

[6] Ibid., 201.

[7] Jonathan Sacks, One People (Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1993), 156

[8] Alasdair MacIntyre, “Torah and Moral Philosophy,” in Radical Responsibility: Essays in Ethics, Religion and Leadership Presented to Chief Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, edited by Michael J. Harris, Daniel Rynhold, and Tamra Wright(Maggid Books, 2013), 11.

[9] Ibid., 3.

[10] Ibid.