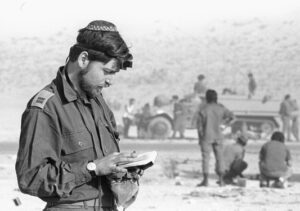

Faith in a War to Remember

While we marked the 50th year since the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War last week, it is important to recall that hostilities lasted almost three weeks until the ceasefire and that soldiers remained stationed on the Syrian and Egyptian borders for many months thereafter. TRADITION’s recent issue on this half-century milestone since the 1973 war was put to good use during the Yamim Noraim; various rabbis report that they made use of its content in their sermons and teaching, and we are pleased to share this sensitive sermon delivered by R. Mayer Waxman before Yizkor on Yom Kippur in the Young Israel of Jamaica Estates.

While the Mahzor refers to Rosh Hashana as “Yom HaZikaron,” the Day of Remembrance, it is nevertheless on Yom Kippur that we say Yizkor – that we remember our loved ones who have passed away. This Yom Kippur 5784 it is important that we also remember Yom Kippur 5734, fifty years ago today, when Egypt and Syria led a coalition of Arab states in a stealth attack against the 25-year young State of Israel, and we should remember the 2,656 Israeli soldiers who lost their lives in that war.

While the Mahzor refers to Rosh Hashana as “Yom HaZikaron,” the Day of Remembrance, it is nevertheless on Yom Kippur that we say Yizkor – that we remember our loved ones who have passed away. This Yom Kippur 5784 it is important that we also remember Yom Kippur 5734, fifty years ago today, when Egypt and Syria led a coalition of Arab states in a stealth attack against the 25-year young State of Israel, and we should remember the 2,656 Israeli soldiers who lost their lives in that war.

The current issue of the TRADITION journal, not just to mark this inauspicious occasion but to help understand it, published “a cluster of articles and essays exploring the theological, national, and communal impact of that nearly calamitous episode in modern Jewish history on the State of Israel, world Jewry, and on Religious Zionism.”

Two articles of note come from two founders and roshei yeshivot hesder, R. Yehuda Amital זצ”ל, the late Rosh Yeshiva of Har Etzion, and R. Haim Sabato יבלח”א, Rosh Yeshiva of Birkat Moshe in Maale Adumim. Their presentation styles are vastly different, but both provide information that is valuable and relevant to our Yizkor, our Yom Kippur, and our ongoing efforts to live meaningful lives.

R. Amital was already almost 50 years old when the war was thrust upon Israel, and his yeshiva, “Gush,” was about 5 years old. His essay, originally published in Hebrew in 1974, was based on an address he delivered to his talmidim less than a month following cessation of the war’s hostilities. The translator of this piece notes that “the number of students in Yeshivat Har Etzion who lost their lives in the Yom Kippur War was significant, and this impacted R. Amital profoundly as was apparent from his essays and speeches from then on. The book this essay appeared in is dedicated to the memory of the eight Har Etzion students who lost their lives in the war: Avner Yonah, Amaziah Ilani, Asher Yaron, Binyamin Gal, Daniel Orlick, Moshe Tal, Raphael Neuman, and Sariel Birnbaum, z”l.”

The macro-level concern of R. Amital’s essay is “What is the meaning of the Yom Kippur War?” He poses this question against, what he calls “the background of our definite faith that we are living in a period of the at’halta di-ge’ula, the first flourishing of redemption,” citing the Talmud statement that war is also the first flourishing of redemption” (Megilla 17b). In that vein, he brings proof that “When one speaks of war, one should view things with a biblical eye,” and that the war was a milhemet mitzva – presenting a religious obligation for Jews to fight. He then provides “three reasons to view the Yom Kippur War through a Messianic perspective.”

But R. Amital’s study touches on issues instructive for our own properly observing Yom Kippur. On the one hand, he brings sources to show that “All of the troubles and suffering which have occurred to the Jewish people in every generation and in every era, including the troubles and suffering of which the prophets spoke and which the Sages foresaw…none of these sufferings are required to occur in the larger scheme of things.” He quotes the Or ha-Hayyim that, basically, redemption can come an easy way or a hard way. The Or ha-Hayyim states: “If the redemption occurs through the agency of Israel’s merit, it will be an event, wondrous in stature, and the Redeemer of Israel will be revealed from heaven with a miracle and sign . . . but this is not the case if the redemption occurs because the designated time has arrived and Israel is unworthy of it—in such a case it will occur in a different manner” (Or ha-Hayyim to Numbers 25:17).

Yet, R. Amital finds a relevant, concrete, and, arguably “easy” corrective action for us to take: He says, “This fact—that the redemption could come without suffering, but that it is coming [currently] accompanied by suffering—obligates us in the positive mitzva of crying out to God, of introspection, of reflection on our deeds, and knowing that God expects us to repent.” (See Rambam, Hilkhot Ta’aniyot 1:1-3.)

R. Amital takes issue with a tendency he observed following the Yom Kippur War—one which is only too familiar to those who read contemporary Jewish responses to trauma. He notes “there is a sense that repentance is a positive obligation which other people are commanded to perform. Wherever you turn, you hear, ‘The war broke out and caused what it did because of the sins of Am Yisrael—certainly because of the sins of those Jews, those military figures, those political leaders, in all of whose words are expressed the arrogance of ‘it is my might and the strength of my hand [which has caused all my success!]’ (Deuteronomy 8:17).” But he looked at events in a most contrary fashion, stating “I believe that if God does have a claim against anyone, first and foremost, it is a claim against those Jews, believers, children of believers, who are immersed in the beit midrash.” This is obvious to him because “If God wishes to lay a claim against others then it would make sense to make that claim for far more serious things” than the arrogance expressed by the verse. “If there is a claim to be made, it is against us!”

But, importantly, he makes a caveat to the prohibition of taking credit for our accomplishments, claiming that it is “permitted to say, ‘it is my might and the strength of my hand’ as long as we [heed the very next verse—’remember the Lord your God, because it is He Who gives you the power to succeed!’” He quotes the 14th century Rishon R. Nissim of Gerona that the meaning is that: It is true that certain people have abilities in one area or another. Just as there are some people receptive to receiving wisdom, others are receptive to devising strategies to collect and acquire wealth. Accordingly, there is some truth in a wealthy person saying, “It is my might and the strength of my hand which has caused all my success!” But what the verse is instructing us is that “seeing that this power is planted within you, be sure to remember Who it was who placed that power within you, and from whence it comes!” Nowhere does it state, “You must remember that the Lord your God gives you success.” People are not always given direct success, rather God grants us power and ability with which to achieve – and the Torah is telling us, that “Since that granted power is what generates this wealth, remember the Giver of that power” (Derashot ha-Ran #10). We need to be grateful for all the strengths and unique talents God imbued in us and thank Him for the opportunities to capitalize on those talents for our own benefit and the benefit of our families and community. And of course, at Yizkor we must remember our loved ones in that light – remember what was special and unique about them and how those qualities enriched our relationships with them.

R. Haim Sabato was a 21-year-old yeshivat hesder student soldier when Israel was attacked. Aside from his role as a Rosh Yeshiva, he is a celebrated novelist, his most well-received book being his Te’um Kavvanot (Adjusting Sights), a fictionalized memoir of the experiences that he and his comrade-havrutot endured in the Yom Kippur War. R. Sabato’s personal, emotional and evocative writing style differs from Rav Amital’s pensive, penetrative, philosophical style. Through the voice of his characters, including his own autobiographical projection into the novel, he writes of differing perspectives of faith at times of sadness and loss, which have universal applicability.

In his essay in TRADITION – and I thank my yeshiva apartment-mate R. Jeffrey Saks, editor of the journal, for his poetic translation – R. Sabato recounts a memorial event he attended 25 years after the war, for his fallen comrade Yeshayahu Holtz, who, with Shmuel Orlan, was killed in the tank right next to his. The event included a panel of now-rabbis who were in the war. He remained quiet during the conversations that followed his co-panelists’ presentations, “after all,” he notes, “who could understand what we went through?”

After some general questions, the moderator asked R. Sabato: “What happened to your faith in the war?” R. Sabato reports, “I started to answer, the words flowed out as if talking to myself, again and again, I went back to those hours. Who knows how many times I went back to them. Maybe every day, maybe every night. Moments when the tank commander shouts to me over the radio: ‘Fire! Fire! They’re shooting at us! Sabato, pray!’ And I exert all my strength and cry out: Ana Hashem, hoshi’a na! Save now, I beseech thee, O Lord! Save now, I beseech thee, O Lord! At that moment the secret of prayer was revealed to me, and the secret of faith that fills all the chambers of the heart.”

When pressed by the moderator, “What of the pain, the fear, the burnt tanks around you, your good friends—what did it do to your faith?” “I answer him: Every moment my faith grew stronger. I can’t explain to you why. Maybe because I saw with my own eyes what a person’s life is, and I stood alone in front of my Creator. Perhaps from the power of a pure, simple prayer.”

Also attending the event was R. Shimon Gershon Rosenberg, known as Rav Shagar. They attended yeshiva high school together and continued learning together in Yeshivat HaKotel. Together they fought in the war.

“I listened to my friend’s words carefully,” said Rav Shagar in response. “It is clear that he speaks the truth. That’s how he felt. But I didn’t feel that way. I’ve wanted to tell him this for a long time since I read his book about the war. When I saw what happened to my dear friends and the tanks around me, I was beset with terror. It’s terrifying to see a life cut short. Shaya and Shmuel, young men full of charm and grace, a grace of purity and uncommon spiritual beauty, sitting on the turret of the tank learning Gemara naturally and innocently. I understand this terror as the ‘yir’a ila’a,’ the ‘higher awe’ written of in Hasidic books. It is frightening, because through it we encounter the mystery of eternity, the mystery of life. I also feel this terror towards life itself, the life that continues. I feel that I am living on borrowed time, I am living on grace for which, from a human perspective, I can find no explanation. And life is constantly accompanied by deep reproach: How do I live this life that is nothing but a free gift…”

Shagar continued, “We are hiding in the shadows, the shadows of faith. God’s providence, in which we all believe, was hidden in the shadows, not in the light. He is a Hidden God, we experienced Him through hester panim, His inscrutable obscurity.… Faith is often found in hard questions, the sort that Rabbi Nahman of Breslov says there are no answers to. But David already said in Psalms: ‘A broken and a contrite heart, O God, Thou wilt not despise.’ God is found inside a broken heart, the feeling of brokenness is itself a divine presence greater and higher than any other. The anguish, the injustice that one may feel in such a situation, perhaps even the sense of shame, actually brings a kind of faith, a deep faith in a hidden God.”

At Yizkor, we face our losses. Circumstances vary, of course, but with every loss – every death of a loved one – comes pain, sadness, and maybe, at some level, a confrontation with faith. These two contrasting but authentic Torah-rich perspectives on faith can perhaps help us compartmentalize and process our own reactions and emotions.

R. Amital relevantly notes that “Another duty emerges from that first obligation of crying out to God—that of gratitude.”

The Mishna states, “‘[You shall love Hashem] with all your might.’ This means, for every measure which He measures to you, you should thank Him tremendously” (Berakhot 9:5). And the halakha states: If one’s father passes away, one makes the blessing, “The true judge.” If the father had money which he inherits: if he has no brothers, he also makes the blessing, “Sheheheyanu”; and if he has brothers, instead of “Sheheheyanu,” he makes the blessing, “One who is good and does good” (Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 223:2). This is the halakha! Even when the pain is great. Even when many, many families are mourning, the pain does not erase the obligation of gratitude.

In the middle of his study, R. Amital offers this guiding perspective: “One needs to know that the purpose of suffering is not only punishment. Suffering is also cathartic and it educates. Suffering has educational goals that could be completely distant from the sins that caused the trouble. An educational goal elevates a person through the path of suffering by a process of inserting [into a person] an awareness and sensitivity in a particular realm or direction, a process that could be lengthy or short. Clearly, it all depends on us, and us alone.”

From our mortal perspective, war and death are never easy to understand. They are rife with emotional burdens and personal tragedies. But Torah and those who immerse themselves in it can provide us guidance and some solace and hope. On this 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, R. Sabato reminds us that there is no “wrong” faith reaction to tragedy and trauma, as long as we ultimately imbue it with a Torah perspective. R. Amital reminds us that at times of tragedy, we dare not blame others, rather we must ourselves undertake teshuva for our own shortcomings. Conversely, he reminds us that God grants every individual unique strengths and abilities. We should appreciate that specialness in others and must capitalize on our own for our and for others’ benefit. He stresses the need for crying out to God and for teshuva. And he reminds us to be grateful for what we have and who we had, even once they are gone – a valuable lesson on which to begin Yizkor, and with which to begin a new year.

Rabbi Mayer Waxman is the Executive Director of the Queens Jewish Community Council.