REVIEW: We Are Not Alone

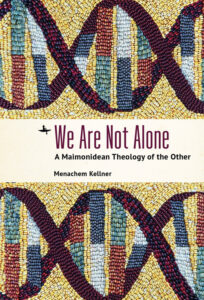

Menachem Kellner, We Are Not Alone: A Maimonidean Theology of the Other (Academic Studies Press, 2021), 191 pages

In 1987, my late father, Rabbi Cyril Harris zt”l became Chief Rabbi of South Africa. I had major misgivings. My parents were leaving behind a great deal that was comfortable and secure in London. My father was leaving his position as the successful rabbi of one of the United Kingdom’s most prestigious Orthodox Synagogues. My mother was giving up her longstanding partnership in a leading law firm. In London, they had been in close proximity to family and surrounded by good friends.

The contrast between the amenability of London life and what seemed to await my parents in the South Africa of the time was striking. They were setting off into totally unfamiliar territory. Far worse, South Africa was inescapably identified in the Western mind with a single overriding issue: Apartheid. It was common knowledge that religious leaders who spoke their minds from within the borders of South Africa often placed themselves in danger, and the risks seemed intensified in light of the then-recent declaration of a State of Emergency by the South African government. It seemed to me that my father was going to be placed in an impossible dilemma: either speaking out against injustice and risking harassment from the Apartheid regime, or remaining silent and thus becoming complicit in the status quo – shetika kehoda’a dami.

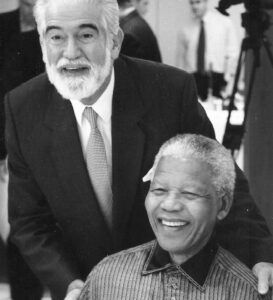

I well remember the disturbing attitudes I encountered on visits to South Africa among some (by no means all) in the Orthodox community early in my father’s tenure. These ranged from overt racism to unwillingness to challenge the discriminatory status quo in any way and total marginalization of the Apartheid issue. Some rabbis I spoke to even believed that “on principle” they should never address the country’s burning moral issue from the pulpit but instead focus solely on internal Jewish concerns. Thank God, my parents succeeded in expressing opposition to Apartheid from the outset without incurring the wrath of the authorities. And salvation was not long in coming. The release of Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990 heralded a new era for the country in which the key challenge facing my father would be guiding the Jewish community into the new democratic South Africa. And that he did with great distinction, demonstrating that a rabbi’s uncompromising fidelity to halakha and Orthodoxy need not be accompanied by ethical myopia but could go hand-in-hand with a broad, generous, and universalistic outlook. A photograph of my father and Mandela embracing at the Presidential Inauguration in 1994 captures, better than a thousand words, the Kiddush Hashem engendered by this approach.

I therefore admit, for reasons of general hashkafa as well as family pride and upbringing, to being strongly predisposed in favor of Menachem Kellner’s project in We Are Not Alone. The overall aim of Kellner’s book is to articulate a universalistic interpretation of Orthodoxy which emphasizes the Torah’s explicit teaching that all human beings are created in the image of God. We Jews are not alone in the universe that God has created. Non-Jews matter to God, and should matter to us, rather than being considered merely the incidental backdrop to our internal Jewish pursuits. Kellner describes the Judaism he champions as one which broadly follows in the footsteps of Rambam rather than those of R. Yehuda Halevi, who argues in the Kuzari for essentialist differences between Jews and non-Jews and the ontological superiority of the former over the latter. I say “broadly follows in the footsteps of Rambam” because Kellner stresses that his outlook is Maimonidean in the sense of being deeply influenced and shaped by the thought of Rambam rather than following Rambam’s views in every respect. Kellner does not claim that the universalistic motif that he privileges is unchallenged by many particularistic teachings in Jewish tradition but only that a universalistic worldview can be legitimately grounded in the historical texts of our faith.

We Are Not Alone is, like all of Kellner’s writings, admirably clear and engaging. Moreover, while being well-argued, it is also very passionate. Kellner himself makes clear that “[t]he book before you is not a scholarly treatise (even if based on much scholarship)” (163). As with many of Kellner’s previous books, this makes for a powerful blend, with Kellner deploying his scholarship to make a case that is simultaneously textually grounded and deeply heartfelt regarding the desired ethos and direction of contemporary Orthodoxy.

We Are Not Alone is, like all of Kellner’s writings, admirably clear and engaging. Moreover, while being well-argued, it is also very passionate. Kellner himself makes clear that “[t]he book before you is not a scholarly treatise (even if based on much scholarship)” (163). As with many of Kellner’s previous books, this makes for a powerful blend, with Kellner deploying his scholarship to make a case that is simultaneously textually grounded and deeply heartfelt regarding the desired ethos and direction of contemporary Orthodoxy.

There is much knowledge and insight for the reader to glean as Kellner goes about developing his argument. The book is worth reading just for the rich and lucid footnotes which provide a wealth of information on a wide range of topics relevant to the book’s central ideas and helpful references to important scholarly literature. Turning to the main body of the text, the reader who considers Kellner’s expositions and analyses of Rambam throughout the book is rewarded with a very instructive overview of Rambam’s thought. Kellner valuably supplements more familiar themes such as Rambam’s universalism and rationalism by emphasizing such motifs as the austerity and abstractness of Rambam’s ideal conception of Judaism, and in particular of his conception of God. Important discussions of particular Maimonidean texts include Kellner’s novel reading of the Guide of the Perplexed III:32, the chapter containing Rambam’s well-known views on korbanot but which, Kellner argues in Chapter 1, contains a great deal more of far-reaching significance. Some of Kellner’s conclusions regarding Rambam’s positions – for example, to focus again on Chapter 1, that for Rambam, not just korbanot but halakhic ritual in general is a concession to human frailty – may be startling to some readers but are so cogently supported that they cannot be ignored and thus invite us to delve deeper in our understanding of Rambam.

In a similar vein, many readers may feel deeply uneasy or skeptical about Kellner’s argument in the book’s final chapter that to be intellectually consistent, halakhists who argue based on Rambam that Christianity is avoda zara must accept that Rambam would similarly label as idolatrous the monotheism believed in by many contemporary Orthodox Jews. This is so, Kellner argues, because Rambam insists that worship of God while being mistaken in one’s conception of Him constitutes avoda zara. Such mistakes, in Rambam’s view, include widespread beliefs such as the kabbalistic idea that mitzvot serve a theurgical purpose, impacting on the structure of Divinity. Kellner’s argument, even if disagreed with, must be engaged with rather than disregarded or dismissed.

There can be little doubt that in We Are Not Alone, Kellner is addressing what is, from the perspective of those who take seriously and with great pride the universalistic strand in our tradition, a very significant problem within the global Orthodox community. Jeremy Brown has recently documented how some Orthodox rabbinic writers view the global Corona pandemic as having occurred solely for the purpose of conveying a Divine message to the Jewish people. Moreover, while recent years have witnessed a welcome increase in Orthodox engagement in humanitarian causes as well as pressing global issues such as the environment, this has largely not been the case in the Haredi world. Indeed, a more universalistic outlook seems to be one defining feature of Modern Orthodoxy as opposed to Haredi Orthodoxy. But much of the Modern Orthodox world remains resolutely inward-looking. Furthermore, as Kellner points out (10 and 34), while extreme particularistic views have plenty of precedent in Jewish tradition, for millennia they were not the basis for real-life policy proposals as they are nowadays, for example in the extremely disturbing and problematic book Torat HaMelekh. Given the blessed reality of renewed Jewish sovereignty in our era, radical particularism now poses a far more direct and concrete moral threat.

One can heartily endorse Kellner’s overarching universalistic stance and much of his evidence and reasoning in support of the traditional legitimacy of that stance maintaining reservations about certain particular arguments. A case in point is Kellner’s suggestion that the claim by some Jews of innate superiority over non-Jews may stem from lack of self-confidence (31, 38). Perhaps it could be equally suggested, however, that Jewish claims of innate superiority stem from too much self-confidence and a narrow view of reality in which the non-Jewish world is merely, as Kellner puts it, “background noise.” One might also claim, as Kellner notes elsewhere in the book, that emphasizing the universalistic dimensions of Judaism simply reflects a desire to portray traditional Judaism as compatible with modern liberal values. While I believe that Kellner is on strong ground in his overall universalistic approach, psychological speculations can cut both ways (or multiple ways) and should remain marginal to the persuasive case he presents.

Kellner notes in the book’s Conclusion that as far as combatting essentialist notions of Jewish superiority and respecting the non-Jewish “Other” is concerned, there is “much work still to be done. That is the point of this book” (161). One might reasonably worry, though, that those within the Orthodox community who most need to read Kellner will likely not do so. This, of course, is no fault of the author. In his writings he has consistently, over many years, communicated his universalistic and morally robust Maimonidean Judaism in different ways, from different angles, and in different languages, English as well as Hebrew (as in another recent work, Gam Hem Keruyim Adam: Ha-Nokhri be-Eynei ha-Rambam [Bar-Ilan University Press, 2016]). But it is hard to imagine that most of his readers do not already share his cultured, humane, and sophisticated version of Modern Orthodoxy, and indeed Kellner writes explicitly that he is writing for those who endorse his basic universalistic stance (xii). One hopes, nevertheless, that Kellner’s works will radiate ever outwards, beyond his natural constituency, to encompass those in the Orthodox world who would gain breadth, depth, and nuance in their understanding of some fundamental aspects of Judaism by encountering his writing.

Meanwhile, rootedness in the particular texts and traditions of Judaism together with compassionate universalism remains an all-too-rare combination in today’s Orthodox world. This book, like Kellner’s many others, provides strength and support for those convinced that the noblest stance for Orthodoxy is one that reaches out from a non-negotiable matrix of halakhic fidelity and proud particularity to embrace all those created in the image of God.

Michael J. Harris, Ph.D., is Senior Rabbi of the Hampstead Synagogue, London, Visiting Research Fellow, Jewish Studies Program, Central European University and Senior Research Fellow at the London School of Jewish Studies.

1 Comment

I’ll have to buy the book and, after reading myself, give it to a friend, also an American Israeli in Jerusalem, who is a bit more particularistic(?) than I am.