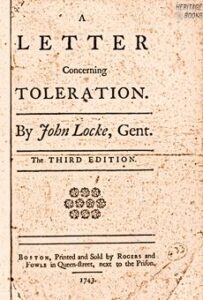

The BEST: A Letter Concerning Toleration

Summary: John Locke’s A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) articulates important principles in favor of religious freedom. He argues for a kind of separation between church and state based on the idea “that the whole jurisdiction of the magistrate reaches only to these civil concernments… and that it neither can nor ought in any manner to be extended to the salvation of souls.” Locke places a number of limits on this toleration including to religious groups that would constitute a “foreign jurisdiction in [a magistrate’s] own territory” and to atheists.

From the perspective of political theory, Locke contends that “it appears not that God has ever given any such authority to one man over another as to compel anyone to his religion.” On a practical level he adds that this would not be successful, because the government’s “power consists only in outward force; but true and saving religion consists in the inward persuasion of the mind.” This assumes Locke’s definition of religion – that is, his contention that a Church “is a free and voluntary society” where “nobody is born a member of any church,” and “no man by nature is bound unto any particular church or sect.”

Why this is The BEST: Every few months, the Jewish world and Jewish state is roiled by another religion-state conflict. These disagreements invariably revolve around the autonomy desired by various individuals and communities versus the standards and enforcement powers of the Orthodox rabbinate empowered by the State of Israel. Who decides what types of prayer can take place at the kotel? What are the standards for conversion? These conflicts would benefit from a reading of Locke’s A Letter Concerning Toleration.

Why this is The BEST: Every few months, the Jewish world and Jewish state is roiled by another religion-state conflict. These disagreements invariably revolve around the autonomy desired by various individuals and communities versus the standards and enforcement powers of the Orthodox rabbinate empowered by the State of Israel. Who decides what types of prayer can take place at the kotel? What are the standards for conversion? These conflicts would benefit from a reading of Locke’s A Letter Concerning Toleration.

In a number of his writings, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks zt”l asserts that “Judaism must be depoliticized… far removed from all structures of power.” Though “Judaism does not recognize the concept of separation of church and state,” he insists on “the separation of powers between king, priest, and prophet.” This is because when “religion enters politics, it becomes a divisive, not a uniting, force. If it seeks power, it will forfeit influence.” Such a perspective can even lead to the “altruistic evil” of religious wars, as occurred in 17th century Europe. As with Locke, R. Sacks argues that government should reject any interest in spiritual salvation.

In a Jewish Review of Books essay Rabbi Shlomo Riskin rejects this “simple disjunction” by succinctly saying that “without power, how can the chosen people protect the powerless against their exploiters? And, of course, without power, how can the chosen people protect themselves?” Therefore, religion “will be unable to redeem without power.” Like Locke, R. Riskin recognizes the power of religious ideas to create political and social goods. Locke’s tolerance had limits (including atheism). R Riskin succinctly highlights the dilemma when he states: “Power may corrupt, and absolute power may corrupt absolutely, but powerlessness corrupts too, for it necessitates accommodation with, and sometimes even surrender to, evil.”

R. Sacks responds that “Judaism never advocated powerlessness, but it did protest attributing religious significance to power” to which R. Riskin then writes a rejoinder. As Israel navigates its conversion crisis or the sincere desire of certain Jewish communities to have mixed-gender prayers at the kotel, the rabbinate’s reliance on power alone will cause a backlash. The abdication of power, however, will create chaos in the public square. Maintaining certain public religious standards need not compel religious action, but it may insist on preventing some public behaviors that violate those standards.

Rabbis Sacks and Riskin argue on the practical level. Locke, however, explains the philosophy behind religious tolerance. Locke’s contention that “nobody is born a member of any church” does not reflect a Jewish understanding of religion. Judaism is more than a set of beliefs. We are born as Jews with obligations. While individuals may choose otherwise, that choice is not recognized as halakhically valid. These differences are critical in understanding the tension between individual freedom and national identity today. Israel needs religious toleration, but it must have different underlying principles than those of Locke. As we celebrate, the blessing that is Jewish power in a modern nation-state may we also embrace the challenges that such power generates.

Rafi Eis is the Executive Director at the Herzl Institute. Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.