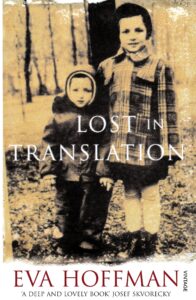

The BEST: Lost in Translation

Summary: Eva Hoffman’s 1989 memoir Lost in Translation: A Life in a New Language presents America as more of an exile than an Eden for Jewish immigrants. Mimicking and subverting more traditional (North) American Jewish memoirs, Hoffman problematizes the linear positive portrayal of the immigrant experience. She stresses how when she first arrived in Vancouver, the land seemed “vast, dull and formless;” the mountains were “too big,” “too forbidding,” and the scenery looked like a “picture postcard…something you look at rather than enter” (100).

Summary: Eva Hoffman’s 1989 memoir Lost in Translation: A Life in a New Language presents America as more of an exile than an Eden for Jewish immigrants. Mimicking and subverting more traditional (North) American Jewish memoirs, Hoffman problematizes the linear positive portrayal of the immigrant experience. She stresses how when she first arrived in Vancouver, the land seemed “vast, dull and formless;” the mountains were “too big,” “too forbidding,” and the scenery looked like a “picture postcard…something you look at rather than enter” (100).

Her memoir is narrated from the point-of-view of a first-generation immigrant of Polish-Jewish descent, reexamining her relationship to the Holocaust, homeland and language. By reflecting on her earlier childlike perception of the world, Hoffman constantly reframes the people and places she encounters so that the reader understands how the overly optimistic depictions of the immigrant experience often complicated the reality that proved to be more harrowing than expected.

Why This is The BEST: Hoffman’s book is divided into three sections, “Paradise,” “Exile,” and “The New World,” mirroring elements of Mary Antin’s autobiography, The Promised Land. In these sections, Paradise takes place in Poland, while Canada and America are the locations of exile and the backdrop for Hoffman’s adolescence and immigration. At the end of the “Exile” section Hoffman writes:

I have come to a different America, and instead of a central ethos, I have been given the blessings and the terrors of multiplicity. Once I step off that airplane in Houston, I step into a culture that splinters, fragments, and reforms itself as if it were a jigsaw puzzle dancing in a quantum space…. perhaps it is in my misfittings that I fit… From now on, I’ll be made, like a mosaic, of fragments—and my consciousness of them. It is only in that observing consciousness that I remain, after all, an immigrant” (164).

Movement doesn’t only move forward, and people do not simply work towards a sense of wholeness. Rather, for Hoffman, people and places are meant to be fragmented, as Hoffman concludes: “it is in my misfittings that I fit.” She sees her “awareness” of the fragmentation as a means from which she can disassociate from the negative connotations with the fragmentary and transform it into an ability to be part of something beautiful—the immigrant as mosaic, the fragmentary as ideal.

Hoffman makes her specific story relatable to broader struggles around immigration, Jewish identity, generational trauma and language. With exquisite storytelling shifting back and forth between the past and the present, she reminds readers how one is always being shaped by their childhood, while also having the power to reshape their relationship to it. As a second-generation descendent of Holocaust survivors, I appreciated the delicate way that Hoffman describes trying to access her parents’ Shoah stories while understanding that they are inaccessible in their entirety. By attempting to piece together fragments, she captures how the shadow of the Holocaust is part of a Jewish inheritance and how struggling to gather the pieces of the past is always part of our present.

Na’amit Sturm Nagel is the Associate Director of The Shalhevet Institute and is pursuing a Ph.D. in English Literature at UC Irvine. Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.