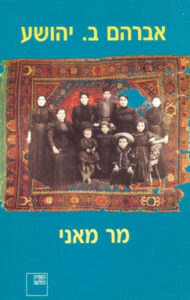

The BEST: Mr. Mani

Summary: A.B. Yehoshua, who passed away last week at age 85, will rightfully be remembered as one of Hebrew (and world) literature’s greatest writers. Among his most important and successful works, in Hebrew and in international translations, is his 1990 novel Mar Mani (skillfully translated by Hillel Halkin as Mr. Mani, for Doubleday, 1992). The novel traces multiple generations of one Jewish family in five distinct conversations, working backwards from 1982 Jerusalem, in the thick of the Lebanon War, back to the mid-19th century. The chapters present five separate narrators encountering six different members of the Mani family over nearly a century and a half, each of whom stands at a decisive moment in Jewish history. Yehoshua offers a series of one-sided conversations and the reader must intuit the missing side of the dialogue. In this way, the author draws us in as co-creators of the work, as it were.

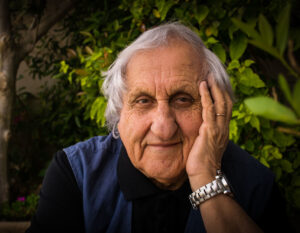

Unlike most of the Israeli Ashkenazic literati of his generation, Yehoshua was born into an old Jerusalem Sephardic family. This complex novel, often compared to the experimental narrative style of Nobel laureate William Faulkner, whom Yehoshua acknowledged as a significant influence, offers a literary historical perspective grounded in the Sephardic experience.

Why this is The BEST: Through the six different generations of Misters Mani, we receive a panoramic view of the Jewish past in exile and return. Working backwards from contemporary Israel, to the Shoah, World War I, the first Zionist Congress, and other events, the novel has been interpreted as a commentary on different stages in the struggle for Jewish identity throughout the modern era. In Mr. Mani, Yehoshua presents a distinctly national saga through the prism of one family. The Manis of each generation, and their interlocuting narrators (only in the final chapter does a member of the family serve as his own storyteller) each represent one of the curious ideological turns Jewish life took over the 19th and 20th centuries – sometimes leading to tragedy, sometimes toward redemption.

In the final chapter, we learn something of the foundational trauma of the Mani family and then are able to read back to the future in the prior conversations to understand how they got this way. In that final episode, when all outer layers of this literary onion have been peeled off, we meet Avraham Mani, born in Ottoman Saloniki at the end of the 18th century, now in midlife, confessing the primordial Mani family sin before his dying rabbi. With this scene, set in 1848 during the birth of European nationalism and revolution, Yehoshua raises questions about Zionism (after all, in its modern, political guise “just” another brand of European nationalism), and how it has reverberated in complex and sometimes contradictory ways. Unlike some leftist readers, to whom Yehoshua was a Prophet, I’m not certain that is the central message of the novel. Rather I see it more as a meditation on larger themes, distinctly Jewish themes, of how the past impacts the present and future. For that alone this fascinating and experimental novel is worthy of our attention.

Alongside his place at the pinnacle of the Hebrew Republic of Letters, A.B. Yehoshua will be remembered as a public intellectual, whose critique of Israel’s place in the so-called “territories” sometimes overshadowed his literary success. One needn’t align with Yehoshua’s politics to agree that modern Zionism carries historical baggage. That’s part of its strength, even part of its moral force. But if we think that Jewish nationalism always gets things right, then we ignore his cautionary historical fiction at our own peril.

On a personal note, despite being an Orthodox Jew living in the very same “territories” he found so problematic, over the final decade of his life I developed a most unexpected friendship with A.B. Yehoshua (his friends universally called him by his childhood nickname, Bulli). This came about as a by-product of my involvement in the world of S.Y. Agnon scholarship. Bulli’s convictions were firm – although he possessed a remarkable ability to reconsider his positions; his supple mind allowed him, late in life, to reverse his 50-year commitment to the Two-State Solution (at least on pragmatic, if not ideological grounds). His reputation as a fiery ideologue masked his personal warmth, love, generosity, and friendship (here’s his “blurb” for my work as editor of the Agnon Library). What did I learn from my interactions with him? He helped cure me of a too-long-held sophomoric idea that those in the Israeli political arena who disagree with me are definitionally enemies of the State or of Judaism. And perhaps also this: Despite now living in Israel for nearly three decades, I cannot fully subscribe to Bulli’s enduring shelilat ha-gola, the passionate sense that Jewish life outside of Israel is inherently flawed. Nevertheless, aside from the realm of Torah and mitzvot, he taught us something about the possibilities of contributing to Jewish life in our own land. Writing in a volume of the Orthodox Forum (2010) I suggested that in America, one’s Jewish identity is voluntary; in Israel one’s Jewish identity is compulsory, be you secular-left or strictly Orthodox. Upon stirring a good deal of controversy among American Jews of various stripes, about 15 years ago, Yeshoshua observed:

We in Israel live in a binding and inescapable relationship with one another, just as all members of a sovereign nation live together, for better or worse, in a binding relationship. We are governed by Jews. We pay taxes to Jews, are judged in Jewish courts, are called up to serve in the Jewish army and compelled by Jews to defend settlements we didn’t want [sic] or, alternatively, are forcibly expelled from settlements by Jews. Our economy is determined by Jews. Our social conditions are determined by Jews. And all the political, economic, cultural and social decisions craft and shape our identity, which although it contains some primary elements, is always in a dynamic process of changes and corrections. While this entails pain and frustration, there is also the pleasure of the freedom of being in your own home.

I am not sufficiently jaded to be uninspired by my friend Bulli’s formulation, yet I recognize that it is precisely this forced interaction which is the source of a great deal of our tension here in Israel. Reading his works of literary fiction will help Israelis, and our Jewish brothers and sisters abroad, to continue to grapple with these complexities for generations to come.

Jeffrey Saks is the editor of TRADITION. Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.