The BEST: Survival in Auschwitz

“The BEST” column highlights the spiritual profit TRADITION’s readership might gain through the encounter with a wide variety of cultural objects. Insight is garnered from surprising places, and even poor cultural products can occasionally heighten our appreciation of more worthy pieces of film, music, or literature. The recent worldwide phenomenon of “Squid Game,” Netflix’s most widely-viewed series ever, is curious considering it is a South Korean production which the rest of the world watched in dubbed or subtitled versions. The program depicts a dystopian survival drama in which gamesters battle one another to the death as a form of entertainment. (Others have treated this trope on television – admittedly with more camp, but also with more moral clarity.) During this week of Kristallnacht commemorations, viewers of “Squid Game” might have reasonably pointed to its resonance with the Holocaust’s dehumanizing impact. In fact, reviewers have observed that the Korean program does not unpack the moral implications of homo homini lupus or depict ennobling moral victories of those suffering chaotic oppression. I come not to critique a show I have read about (but have not watched), but to draw our attention to a more worthy exploration of the themes.

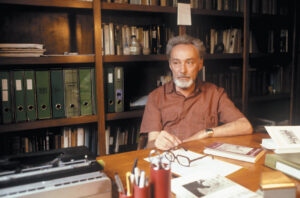

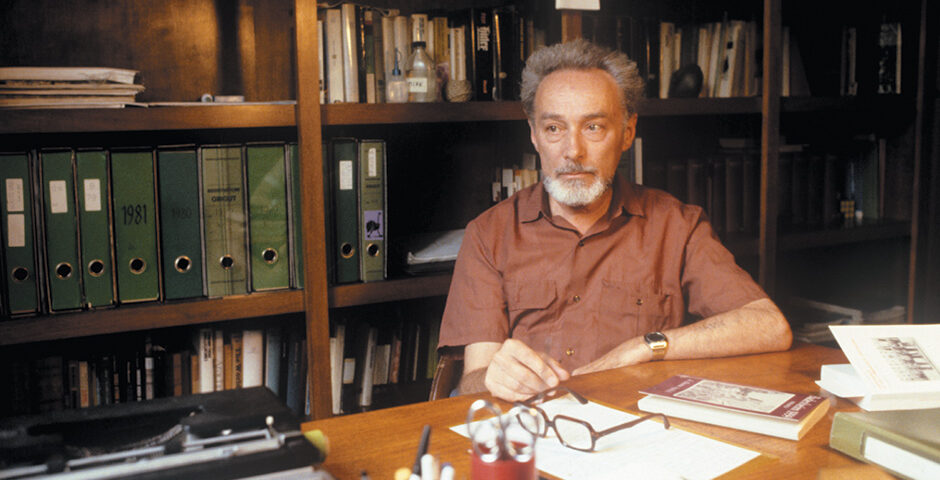

Summary: Primo Levi was born in 1919 in Turin, northeastern Italy, to a liberal Jewish family and spent most of his life there, until his death in 1987 at age 67 in presumed suicide (although the circumstances are debated). A chemist by training and profession, Levi was a member of the Italian resistance, hiding as a partisan in the foothills of the Italian Alps when he was arrested by the Fascists in December 1943. Deported to Auschwitz in February 1944 – tattooed as #174517 – he spent 11 months there until liberation by the Red Army.

After the war Levi made his way back to Turin, where he spent the rest of his career as a chemist in a paint factory (even after achieving international fame as an author). During his first year back home he wrote a Holocaust memoir, which become Survival in Auschwitz (titled outside of United States as If This is a Man?, a more literal translation of the Italian title; American publishers thought “Auschwitz” on the cover would help sales). It was originally released in Italian in 1947, eventually being translated to dozens of languages, and launching a long literary career including almost 20 memoirs, essays, novels, and short stories.

Why this is “The BEST”: Survival in Auschwitz is a remarkable work of incredible moral power – noted for its sobriety and its “still small voice.” Levi said in a 1978 interview: “I thought that my word would be more credible and useful the more objective it appeared and the less impassioned it sounded; only in that way does the witness in court fulfill his function, which is to prepare the ground for the judge. It is you [the readers] who are the judges.”

His subject is not the Nazis’ oppression, humiliation, torture, and murder of millions, but rather how easily humanity can become degraded under such circumstances. In the midst of this debasement he finds rare and astonishing models of heroism: in his language, portraits of men who become “redeemed” even if they are not “free.”

The memoir describes Levi’s friend Lorenzo Perrone, who for six months gave the ill Levi part of his daily bread ration, without asking for anything in return, and thereby kept Levi alive. In contrast to prisoners and guards motivated by self-preservation, Lorenzo preserved his humanity. Levi portrays the sacrificing of one’s own measly mouthful of sustenance as the greatest form of resistance.

However little sense there may be in trying to specify why I, rather than thousands of others, managed to survive the test, I believe that it was really due to Lorenzo that I am alive today; and not so much for his material aid, as for his having constantly reminded me by his presence, by his natural and plain manner of being good, that there still existed a just world outside our own, something and someone still pure and whole, not corrupt, not savage, extraneous to hatred and terror; something difficult to define, a remote possibility of good, but for which it was worth surviving.

During the ten days between the evacuation of the Nazis and the arrival of the Red Army, those left for dead, including Levi, who had enough strength went out to find food and wood; it was proposed that those who toiled to keep the others alive should receive an extra slice of moldy bread:

Only a day before a similar event would have been inconceivable. The law of the Lager [camp] said: “eat your own bread, and if you can, that of your neighbor,” and left no room for gratitude. It really meant that the Lager was dead. It was the first human gesture that occurred among us. I believe that that moment can be dated as the beginning of the change by which we who had not died slowly changed from prisoners to men again.

Tragically, late in life amidst depression, Levi dwelt obsessively over the drops of water he had not shared with fellow prisoners. These themes – the dehumanizing effects of enslavement, and the struggle against them – were also explored in his The Drowned and the Saved (1986). In a description of the cattle car to Auschwitz he describes scores of men, women, and children locked in the train for days and the damage to human dignity of having to relieve themselves amidst the crowd. One person had snuck a chamber pot onto the train (one pot for over 50 people). They find a few nails and a scrap of blanket and improvised a makeshift lavatory. Levi writes: “It was substantially symbolic: we are not yet animals, we will not be animals as long as we try to resist.” But, yet he writes with foreboding, “This was actually [just a] prologue” for what happens once they arrive in the concentration camp. Nevertheless, the reader understands, the struggle for dignity is noble even when futile

The aftereffects were carried by him and his Auschwitz comrades for life. Upon return home he described severe disorientation, his sense of being out of place in the company of man and of himself. Only the catharsis of composing Survival in Auschwitz allowed him to reclaim his own humanity. Like other great artists, he discovered the authentic Jewish response to catastrophe in creativity:

But I had returned from captivity three months before and was living badly. The things I had seen and suffered were burning inside of me; I felt closer to the dead than the living, and felt guilty at being a man, because men had built Auschwitz, and Auschwitz had gulped down millions of human beings, and many of my friends, and a woman who was dear to my heart. It seemed to me that I would be purified if I told its story…. [B]y writing I found peace for a while and felt myself become a man again, a person like everyone else, neither a martyr nor debased nor a saint: one of those people who form a family and look to the future rather than the past (The Periodic Table, 151).

Survival in Auschwitz is introduced by a poem in which Levi challenges his readers to see their own role in the humanization of mankind, and cautions against the dangers of failing to do so. This is not simply a challenge in the Lager but in all human interaction. It invites the reader to make a judgment. It alludes to the treatment of people as Untermenschen (German for “sub-humans”), and to Levi’s examination of the degree to which it was possible for a prisoner in Auschwitz to retain his or her humanity. The poem explains the title and sets the theme of the book: humanity’s struggle in the midst of inhumanity.

The last part of the poem, beginning “meditate,” explains Levi’s purpose in having written it: to record what happened so that later generations will ponder the significance of the events he lived through, and parallels the language of the Shema and echoes the warnings of the biblical Tokhaha cautionary curses:

You who live safe

In your warm houses,

You who find, returning in the evening,

Hot food and friendly faces:Consider if this is a man

Who works in the mud

Who does not know peace

Who fights for a scrap of bread

Who dies because of a yes or a no.

Consider if this is a woman,

Without hair and without name

With no more strength to remember,

Her eyes empty and her womb cold

Like a frog in winter.Meditate that this came about:

I commend these words to you.

Carve them in your hearts

At home, in the street,

Going to bed, rising;

Repeat them to your children,Or may your house fall apart,

May illness impede you,

May your children turn their faces from you.

Levi concludes his memoir-meditation by turning to us, by challenging and charging us: “We now invite the reader to contemplate the possible meaning in [Auschwitz] – of the words ‘good’ and ‘evil,’ ‘just’ and ‘unjust’; let each judge … how much of our ordinary moral world could survive on this side of the barbed wire.”

This too is a message for fans of “Squid Game” (and those who read its reviews).

Rabbi Jeffrey Saks is the editor of TRADITION.

Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series. Read Yitzhak Blau’s “The BEST” column on Primo Levi’s The Drowned and the Saved.