The BEST: The Brothers Karamazov

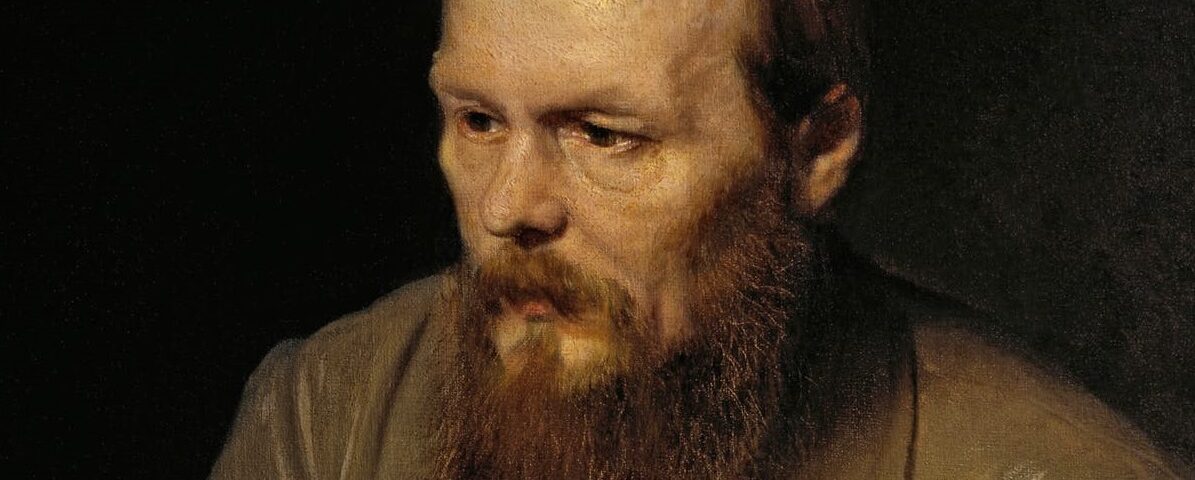

Summary: Set in 19th-century Russia, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov is composed of the stories of three adult brothers, as well as their relationships with their emotionally distant and abusive father. Utilizing a patricidal plot, the book tackles faith, doubt, and reason in the context of a modernizing Russia. With a unique and passionate intensity, it debates eternal questions like God, free will, and morality.

Summary: Set in 19th-century Russia, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov is composed of the stories of three adult brothers, as well as their relationships with their emotionally distant and abusive father. Utilizing a patricidal plot, the book tackles faith, doubt, and reason in the context of a modernizing Russia. With a unique and passionate intensity, it debates eternal questions like God, free will, and morality.

Why this is The BEST: With careful observation and penetrating insight into the manic edges of experience, Dostoevsky crafts novels with a cacophony of compelling and vivid characters. After the harrowing drama of his own early years, Dostoevsky (died 1881) produced several novels of unmatched psychological profundity and socio-political relevance in the last twenty years of his life. Notes from the Underground gives voice to the resentment and spite of a character bent on proving his freedom by engaging in irrational, counterproductive behavior. Crime and Punishment opens on a poor student murdering an old woman and her companion, in the belief that he is superior to moral law and goes on to investigate his ineluctable need to confess and accept punishment. Dostoevsky’s The Idiot depicts the disasters that ensue when a certain kind of social innocence is loosed upon the world. The Demons (sometimes known as The Possessed) brings to life a provincial town in which would-be progressive ideologists give birth, in the next generation, to nihilism, suicide, murder and revolution. The Brothers Karamazov, his final and probably greatest work, is another murder story in which all of Karamazov’s sons had reason to wish their father dead. It contains penetrating, unforgettable arguments about the endless conflict between man’s desire for happiness and the ideal of responsible freedom represented by Dostoevsky’s version of Russian Orthodox Christianity, debates about whether in a created world scarred by horrendous, intolerable evil one ought to “return one’s ticket” to God and leave, whether, in a world without God, “everything is permitted,” and, as elsewhere in Dostoevsky, can we encompass a love that transcends our suffering, our painfully felt psychological landscapes of self-destruction, humiliation, and self-laceration.

The liberalism Dostoevsky excoriated in his fiction and journalism attracted him as a young man. To the point where he was arrested, his execution commuted to a Siberian prison term only at the last second. Throughout his life, the unparalleled student of irrational existence was driven by his own demons: he was addicted to the German establishments depicted in The Gambler and at one point risked losing ownership of the income for his books by committing himself to a barely realistic publisher’s deadline. His emotional attachment to a distinctive brand of Russian religious nationalism went well with Russian chauvinism, anti-Semitism and a sweeping contempt for the Western culture associated in various ways with German philosophy, Victorian England’s practicality, and Roman Catholic authority. He was a very great artist with much to teach us; he was not a person we should want to emulate.

One cannot fall uncritically under the sway of any writer, let alone one as powerful but humanly flawed as Dostoevsky. Let me note a few challenges:

Dostoevsky’s characters are given to extreme behavior and radical mood swings. Yet the insight we gain from what may be a faithful portrayal of a certain kind of Russian or universal aspects of the human condition runs the danger of taking the exaggerated for the norm. To be sure, there are 19th century Russians and 21st century people who act “like characters in Dostoevsky,” yet contemporaries of his like Tolstoy and Chekhov offer more sober and more balanced versions of human crisis.

From realistic literature, we often aim to derive a sense of human beings as individuals who cannot be reduced to a predictable model but whose actions and consciousness are distinctive and unlike any other’s. Because Dostoevsky’s creations are frequently unstable and due to the way they agitate each other it is often as if one is listening to a cacophony or “polyphonic dialogue” and imbibing the atmosphere of a disordered social encounter rather than the voice of a distinct individual. Something like this point is important in the influential 20th century literary criticism of Bakhtin and his school. Taking it seriously means that what we learn from Dostoevsky is different from what we expect from other great realist authors.

Likewise, in the enjoyment and study of realistic literature we often hope for a transition from lack of self-understanding to clarity, from the inchoate empire of id to the constitutional monarchy of ego, as Freud might put it. Dostoevsky does not consistently deliver such enlightenment. Recent critics have argued that many of his major characters seem incapable of self-understanding, as if they had suffered some unmastered profound trauma “offstage” as it were, one of which they are dimly aware, manifested in their repetitive irrationality. If these scholars are right, then it is precisely Dostoevsky’s greatness in forcing us to confront the opaque recesses of human existence that make us, on the one hand, more than merely self-interested calculating rational animals, and on the other hand, subject us to the destructive impulses that debase our collective and individual lives.

Rabbi Shalom Carmy, editor emeritus of TRADITION, teaches Jewish studies and philosophy at Yeshiva University.

Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.