The BEST: The Idea of the Holy

Summary: Rudolf Otto’s The Idea of the Holy distinguishes between two aspects of theism: the rational and the non-rational. The former ascribes to the Divine reason, purpose, good will, supreme power, unity, and selfhood. Otto argues that we cannot allow such terms to confine God within human language. Rather, “the holy” contains a distinct element, beyond its colloquial use as “absolute goodness,” for which he coined the term “numinous.”

Otto goes on to explain the numinous as experience which is “wholly other.” He argues that because the numinous is irreducible, it cannot be defined in terms of other concepts, and that the reader must therefore be “guided and led on by consideration and discussion of the matter through the ways of his own mind, until he reaches the point at which ‘the numinous’ in him perforce begins to stir” (7). The non-rational elements of the holy cannot be taught – they can only be evoked within the person who has already experienced them.

Otto goes so far as to instruct those readers who cannot direct their minds to a moment of deeply-felt religious experience to stop reading his book. He thereby disassociates his text from the normal discursive method – the rational – and reaches to outline the contours of the non-rational. This can only be performed with someone who has a pre-existing experience of the holy.

Why this is The BEST: The 19th century witnessed advances not just in science and technology but also the establishment of an empiricism which argued, “Things that cannot be measured do not really exist.” This conception remains very much a piece of our culture. Writing at the start of the 20th century, Otto cried foul. There’s something within us (and beyond us) that cannot be reduced to external observation. This anti-reductionist approach is a critical weapon in a Ben or Bat-Torah’s arsenal, today. R. Aaron Lichtenstein wrote for the YU Commentator in 1961, “No matter where we live, we are in the midst of a society which is generally indifferent if not hostile to religious values, one in which advancing the development of Torah entails an almost perpetual struggle” (Leaves of Faith, vol. 1, 92). The Idea of the Holy can be a useful weapon in this struggle.

The work exemplifies another role that R. Lichtenstein saw within general studies, to “sustain religion—supplement it and complement it—in a sense deeper and broader than we have hitherto perceived” giving us “insight into basic problems of moral and religious thought.”

In this regard, Otto peels apart the components of non-rational religious experience. He uses Avraham’s words – “I am but dust and ashes” – to describe creature-consciousness, “the emotion of a creature, submerged and overwhelmed by its own nothingness in contrast to that which is supreme above all creatures” (10). He evokes (but cannot positively define) the mysterium tremendum – “sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship… [at times] thrilling vibrant and resonant… [at times bursting] in sudden eruption up from the soul with spasms and convulsions or lead to the strangest excitements” (12). He breaks down this mysterium tremendum into component parts the awe-ful (yir’ah), the overpowering (majestas), and urgency (energy). He sets opposite the awe-fulness and majesty – the attractive and the fascinating.

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik evoked some of these same ideas:

Holiness, according to the outlook of Halakhah, denotes the appearance of a mysterious transcendence in the midst of our concrete world, the “descent” of God, whom no thought can grasp, onto Mount Sinai, the bending down of a hidden and concealed world and lowering it onto the face of reality (Halakhic Man, 46).

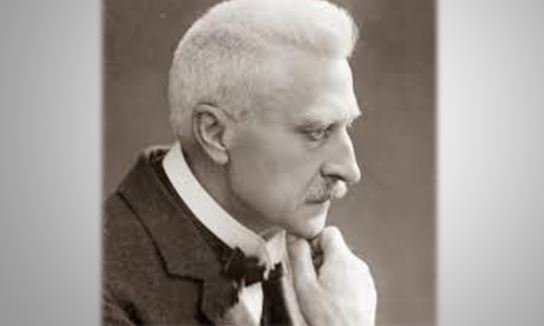

As we make use of this work we must recognize the difference between it and other works contained within The BEST series. Rudolf Otto (Germany, 1869-1937) was an eminent Lutheran theologian. He writes from within a different religious tradition than our own. We have much to gain from his perspective – but it is not Torah. We have our own idea of the Holy. That idea is perhaps best evoked – to some degree in contrast to Otto’s numinous – in the words of R. Soloveitchik:

The dream of creation finds its resolution in the actualization of the principle of holiness. Creation means the realization of the ideal of holiness… If a man wishes to attain the rank of holiness, he must become a creator of worlds. If a man never creates, never brings into being anything new, anything original, then he cannot be holy unto his God… Therein is embodied the entire task of creation and the obligation to participate in the renewal of the cosmos. The most fundamental principle of all is that man must create himself. It is this idea that Judaism introduced into the world (Halakhic Man, 108-109).

Chaim Strauchler, associate editor of TRADITION, serves as rabbi of Rinat Yisrael in Teaneck. Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.

1 Comment

✳️Always good to “ hear “ you