The BEST: The Meaning of History

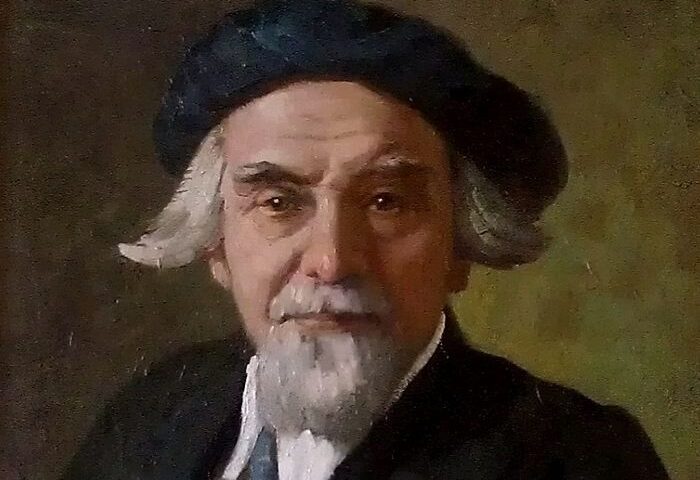

Nikolai Berdyaev

Summary: In The Meaning of History Russian political philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev (1874 – 1948) attempts to revive the philosophy that history laid the foundations for Russian national consciousness. Its categories are centered on distinctions between Slavophiles and Westerners, East and West. In order to grasp and oppose the complex phenomenon of social and cultural disintegration, Berdyaev shows that human beings must rely upon some internal dialectic. After the debacle of World War I, the moment arrived to integrate Russian historical experiences into those of a Europe, which, although torn by schism, still claimed to be the ultimate descendant of Christendom. Along the way, Berdyaev touches on Judaism:

I remember how the materialist interpretation of history, when I attempted in my youth to verify it by applying it to the destinies of peoples, broke down in the case of the Jews, where destiny seemed absolutely inexplicable from the materialistic standpoint… Its survival is a mysterious and wonderful phenomenon demonstrating that the life of this people is governed by a special predetermination, transcending the processes of adaptation expounded by the materialistic interpretation of history. The survival of the Jews, their resistance to destruction, their endurance under absolutely peculiar conditions and the fateful role played by them in history: all these point to the particular and mysterious foundations of their destiny.

Something more profound than a non-Jew affirming Judaism – like Twain of Priestly – is at stake here. The tools of history are not as far-reaching and all-powerful to explain the vicissitudes of their subject as we believe them to be at first sight.

Why this is The BEST: The triumphalism of history, particularly with regard to explaining the Jewish condition of being, reached its apogee in the 19th century with Geiger’s Hochshule fur die Wissenschaft des Judentums. Yet, the historical-critical model, which places a text’s origin above its meaning, still holds sway not so much in the academy as in the pervasive notion that one interpretive lens, be it Marxist or feminist or deconstructionist, can reach so far as to explain comprehensively any phenomenon under investigation.

Berdyaev goes against this grain. He writes that history is a noumenon, not entirely knowable by mere sensory perception. In the early chapters of The Meaning of History (first published in Russian in 1923 and in English in 1936) he speaks repeatedly of the “mystery of the historical,” of history as “a sort of revelation,” and of history as “a myth.” In other words, he lays to rest the misperception at the outset of his discourse by stating that “a purely objective history would be incomprehensible.”

A middle chapter of The Meaning of History is somewhat less roundly praising of the Jewish people. Berdyaev at once appreciates the absolute monism of the Jewish apprehension of the divine while almost on the same page decrying the dualism that prevents Jews from apprehending the “savior” who purportedly arose from our midst. He transfers the enduring messianic teleology via Marx’s class structure to the liberation of the proletariat; which sounds as much like a dialectical materialist trying to square the circle of his own Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The deliberate misreading that must necessarily attend a supercessionist reading of the Hebrew Bible is only somewhat dimmed by Berdyaev’s recognition that Judaism defies any attempt to wrestle it into the confines of deterministic historical models (i.e., that all events are determined completely by previously existing causes). In fact, in this chapter as well as throughout the book, Berdyaev leans on the influence of Jakob Böhme, the early 17th century German philosopher. A Lutheran, Böhme seemed quite aware of the mystical trends in Jewish thought and described a numinous, esoteric strain in Jewish history which obviously resonated with Berdyaev.

Berdyaev is firm evidence both by design and by his example that efforts to constrain the sweep of the Jewish people to one historical, philosophical, or theological view will result in considerable distortion of the subject at hand and ultimately of the enquirer as well.

Joe Kanofsky is the Rabbi of Kehillat Shaarei Torah in Toronto and holds a Ph.D. in Literature.

Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.