The BEST: The Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun

Summary: In fourteenth-century North Africa an Arab Muslim jurist and polymath set out to write a comprehensive history of the world and penned an introductory volume, the Muqaddimah, which laid out a remarkably innovative theory of human civilization.

Summary: In fourteenth-century North Africa an Arab Muslim jurist and polymath set out to write a comprehensive history of the world and penned an introductory volume, the Muqaddimah, which laid out a remarkably innovative theory of human civilization.

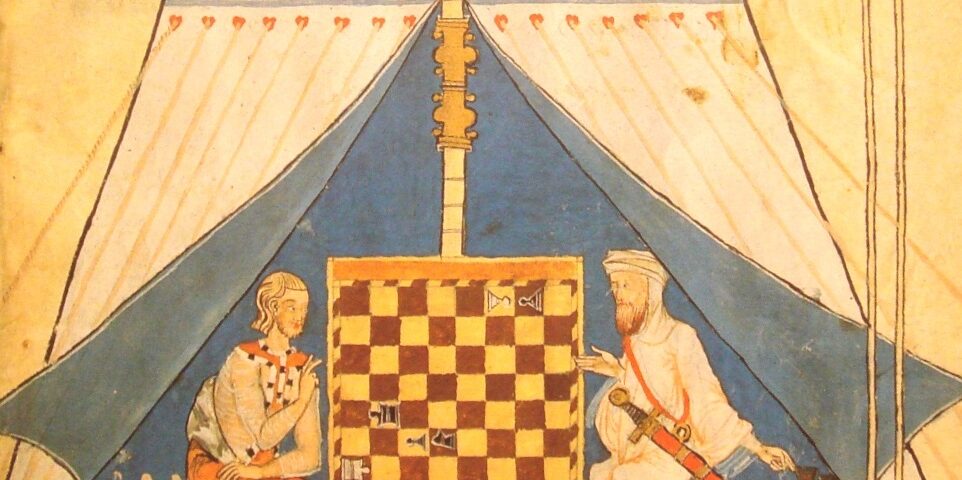

Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406) lived in an era when unified Islamic empires fragmented into small, local, and often short-lived dynasties. He saw the tragic impact of the Black Death, and he described the ruins of once-great cities, laid waste by human absence, economic decline, and warfare. Islamic societies continued to flourish, but Ibn Khaldun took it upon himself to explain a world beset with political uncertainty and social turmoil. He sought to answer a question that troubles all great civilizations reflecting on a gloried past and wary of a sclerotic present. How did we get here?

The work is rich and varied, but at its heart lies a theory of cyclical social change based on the concept of “asabiya.” The term asabiya—appearing several hundred times in the Muqaddimah—connotes social cohesion, a group feeling that constitutes the lifeforce of human civilization. Ibn Khaldun highlights a dynamic tension between sedentary and nomadic cultures. Nomadic groups experience a potent form of asabiya, as the unforgiving environment of the desert demands mutual responsibility and community-based social structures. Asabiya drives these groups towards power, leading them to establish royal authority and statehood in urban settings. States require taxation to fill growing material needs and support political institutions. After some generations, the society becomes enamored with the coddling of sedentary life and descends into decadence. As the pursuit of luxuries and personal glory increases, people become alienated from the rulers and from one another. The loss of cohesion in those societies makes way for a new group with greater asabiya, and the cycle begins again.

The Muqaddimah serves as a kind of Aristotelian first principles for Ibn Khaldun’s multi-volume work of history, Kitab al-‘ibar (The Book of Lessons and Archives). With the precision of a jurist, he breaks down society into component parts and analyzes their function: the forces that drive human civilization; the ways geography and environment shape culture; nomadic and sedentary societies; political authority; economies and livelihood; and various fields of scientific knowledge. Ibn Khaldun is both a product of his intellectual context as well as a pioneer within it.

Why is this The BEST? Most works of medieval Arab history remain the stuff of esoterica, the provenance of historians of the Muslim world. While Ibn Khaldun wrote from within his medieval Islamicate context, the Muqaddimah was a forerunner of several fields of modern social science—including historiography, sociology, and social psychology—to which it offered a useful vocabulary of concepts. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks also demonstrated the Muqaddimah’s cross-cultural utility in his critique of modern western culture. He deploys the concept of asabiya to highlight the social decline that unfolds within wealth-driven and narcissistic societies (Not in God’s Name, 257). It is no wonder that Ibn Khaldun’s ideas resonated with Rabbi Sacks who argued that religion, in general, serves as “a countervoice to the siren song of a culture that sometimes seems to value self over others, rights over responsibilities, getting more than giving, consumption more than contribution, and success more than service to others” (speech in the House of Lords, November 22, 2012).

Our Jewish communities today stand to benefit from engagement with Ibn Khaldun’s civilizational theory, as well. American Jews have become an empowered social and political force. We have built first-class educational institutions, erected great houses of worship, and fostered every form of Jewish artistic and cultural expression. Israel as a Jewish State is a democracy with a thriving economy and public sector. However, along with political empowerment, social acceptance, and economic success, materialism and individualism in our communities are challenging the Jewish value of sacrifice for God, community, and the greater good.

Our soaring synagogues, elegant weddings, and cabinets filled with luxury Judaica can be expressions of hiddur mitzva, sacred beautification. As a means to channel our collective intentions and elevate the holy in our lives, material adornments of our religious rituals can strengthen the ties of community. However, when they become status symbols, testimonies to individual prosperity, they erode our social cohesion. Ibn Khaldun’s schema demonstrates that without intentional intervention, the descent from purpose-driven asabiya to social decay occurs subtly, naturally, and inevitably. The generation that “built the edifice through application and group effort,” according to the Muqaddimah, appreciates its mission to serve collective needs. Those born into a life of comfort and existing institutions, however, “think that it was something owed his people from the start, by mere virtue of their descent.”

The Muqaddimah suggests that blood-ties of family and tribe lie at the center of asabiya, but organizing around God and religion may play a similar role. Pride and jealousy are powerful drivers of human action, writes Ibn Khaldun, but the proper group cohesion around religion causes “the qualities of haughtiness and jealousy to leave them” and “exercises a restraining influence on mutual envy.” Common cause and shared purpose emerge from seeing ourselves as representatives of the Divine on earth, with requisite responsibilities to one another.

Jewish scholars often engage with Islamic works in search of what they may reveal about the thought of our own great luminaries such as Rambam, Sa’adya Gaon, and Ibn Ezra. Rabbi Sacks’ reading of the Muqaddimah is remarkable in that it does not excavate the work for what it says about us, but he channels the wisdom it offers to us.

Ari M. Gordon is Director of Muslim-Jewish Relations at American Jewish Committee.

Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.