The BEST: Vermeer’s “Geographer” and “Astronomer”

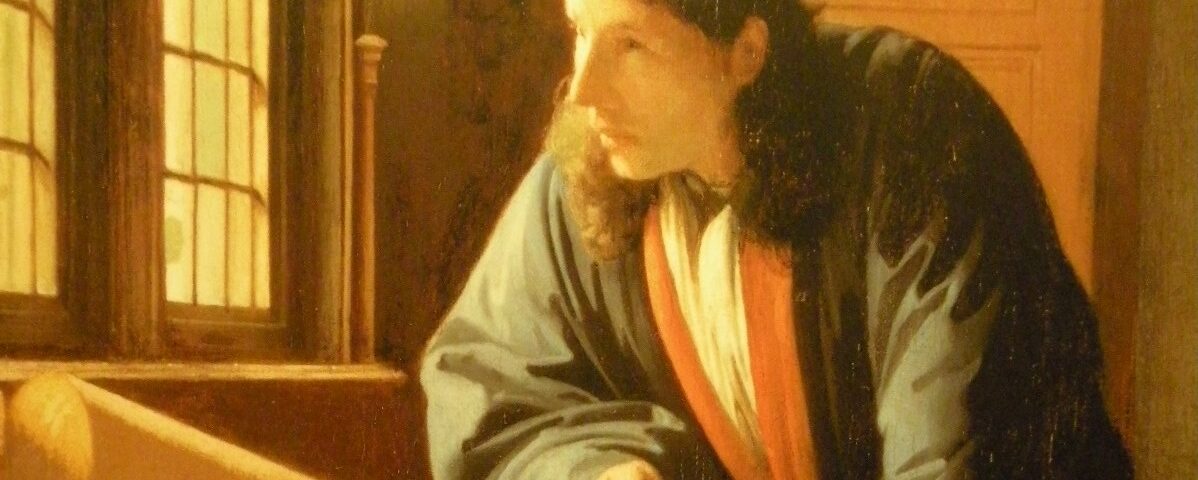

Summary: Johannes Vermeer’s “The Geographer” (1669) depicts a man who is trying to map the world in which he lives. He deals with small matters, trying to orient the small sections of our existence into a comprehensive whole, and the painting clearly depicts a moment of insight—the light streaming in draws our attention to his eyes. He holds his cartographer’s instrument in midair, as if he has suddenly been caught by an idea, and, again, the window’s light shines on those hands for emphasis. Just as the window allows that light in, it allows the geographer’s gaze to escape the confines of the room—emphasizing his interest in the outside world. The globe is tucked away on a shelf behind the geographer and is irrelevant to the enterprise of the mapmaker since it depicts the entire world. Our man is interested in the details. The picture on the wall behind the geographer is that of a sea chart—very much part of the world in which he lives. “The Geographer” is a pictorial representation of the ability of the human mind to inquire about the world and expand the scope of our understanding.

Summary: Johannes Vermeer’s “The Geographer” (1669) depicts a man who is trying to map the world in which he lives. He deals with small matters, trying to orient the small sections of our existence into a comprehensive whole, and the painting clearly depicts a moment of insight—the light streaming in draws our attention to his eyes. He holds his cartographer’s instrument in midair, as if he has suddenly been caught by an idea, and, again, the window’s light shines on those hands for emphasis. Just as the window allows that light in, it allows the geographer’s gaze to escape the confines of the room—emphasizing his interest in the outside world. The globe is tucked away on a shelf behind the geographer and is irrelevant to the enterprise of the mapmaker since it depicts the entire world. Our man is interested in the details. The picture on the wall behind the geographer is that of a sea chart—very much part of the world in which he lives. “The Geographer” is a pictorial representation of the ability of the human mind to inquire about the world and expand the scope of our understanding.

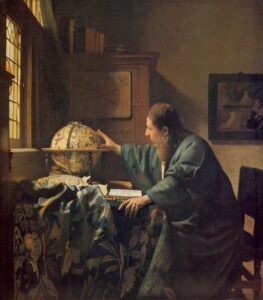

In “The Astronomer” (c. 1668), the surveyor of the heavens holds in his hand the globe with the constellations, indicating his yearning to be part of the greater expanse of creation. Unlike the geographer—caught in mid-action, gazing out of the window—the astronomer is at rest, contemplating his celestial globe. On the wall behind him is a painting depicting the finding of Moses by Bat-Paro. This is one of the great moments of salvation in world history. The Jewish people were saved because the child Moses was drawn from the river. Art historians have pointed out that the inclusion of this “painting within a painting” was meant for allegorical purposes, reinforcing the artist’s underlying meaning—God’s divine providence in the finding of Moses, symbolizing that spiritual guidance in man’s attempt to discover His world.

Why this is The BEST: We may read these paintings midrashically, as it were. They introduce us to the two aspects of human wonder. The geographer tries to measure and describe the world in which he lives; the astronomer tries to understand things that transcend our immediate sphere of creation, to grasp our position in the vast cosmos. We understand salvation as being an act of God’s love, enabling us to reciprocate that love.

Why this is The BEST: We may read these paintings midrashically, as it were. They introduce us to the two aspects of human wonder. The geographer tries to measure and describe the world in which he lives; the astronomer tries to understand things that transcend our immediate sphere of creation, to grasp our position in the vast cosmos. We understand salvation as being an act of God’s love, enabling us to reciprocate that love.

Surely these ideas can be stated in religious language and are found in the words of Hazal. But not everyone can appreciate the wonder in the world through the word, and not everyone can appreciate the love that is expressed in creation through the use of language.

Vermeer enables us to look upon these notions through an amazing representation of reality. For those who make the effort, the interpretation is greatly enhanced by the work of art itself. It gives us the opportunity to stand with wonder before the idea, to be able to find ways of connecting to the Creator through the beauty of the represented creation.

Rabbi Chaim Brovender, a well-known pioneer of Torah education in Israel, is Rosh Yeshiva of WebYeshiva.org. He served as TRADITION’s Associate Managing Editor, 1964-1965. R. Brovender’s thoughts on art and Judaism will continue in The Best in the coming weeks with a look at Rembrandt.

Click here to read about “The BEST” and to see the index of all columns in this series.

1 Comment

[…] is R. Brovender’s second “The BEST” entry on works of classic art. Read his recent column on paintings by […]