Unpacking the Iggerot: Cheating, College & Culture

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Unpacking the Iggerot: Cheating, College & Culture (Iggerot Moshe, Hoshen Mishpat, vol. 2, #30)

Summarizing the Iggerot

1980 was a fraught time for academic integrity within the New York State’s school systems. On June 20th that year, the New York Times featured an article titled “Watch is Under Way for Cheaters As Regents Grading Begins.” New York mandates a series of standardized exams called the Regents, which students are required to pass in order to graduate high school. Amid broader concerns about cheating, there were yeshiva students who purportedly leaked the test banks forcing the issue to be brought to the desk of R. Moshe Feinstein, who at this time was the uncontested leader of the Agudath Israel and broader American yeshiva world.

Unlike a typical responsum which would weigh the merits of both sides, when it came to a matter like this—to borrow the phrase of Tevya the milkman—“there is no other hand.” Rather, the purpose of his responsum was to state in no uncertain terms that Judaism condemns cheating, with no room for doubt or equivocation. Similar to the responsum (H.M., vol. 2, #29), addressed in our previous column “Patriotism, Pragmatism and Particularism,” R. Feinstein identifies several formal halakhic violations:

1) Dina de-Malkhuta Dina: The halakhic obligation to adhere to the laws of the land.

2) Genevat Da’at: Deception of other human beings, whether Jewish or not (see Hullin 94a).

3) Monetary Theft.

4) Lying.

The third point might raise some eyebrows. Granted cheating is unethical, but how does it rise to the level of bona fide theft? R. Feinstein explains that a potential employer might take the applicant’s academic credentials into account during the interview process. The increased score due to cheating may very well gain him the job, thereby preventing someone who actually earned it on the basis of hard work and merit. Even once hired, should the employer need to downsize, he will again grant priority to the cheater. He may even ironically think that this gifted yeshiva graduate is a man of integrity whom he would prioritize keeping in his company. Finally, the entire employment arrangement is entered under false pretenses, which is inherently problematic even absent the aforementioned factors.

R. Feinstein preempts the claim of some diligent yeshiva student who might offer the pretext that to study for his secular exams would constitute bittul Torah (squandering time otherwise used for Torah study), and that better he allocate that time toward his Torah studies. R, Feinstein he dismisses this claim as mere laziness being justified under the veneer of religious piety.

He concludes by reiterating a theme from the previous responsum, which emphasizes the elevated nature and expectations of yeshiva students. This leads him to deny the reports of yeshiva students cheating, claiming that it was fabricated by “haters” of the Jewish people and those who seek to sabotage the yeshivot: “For on the contrary, it is known that yeshiva students are among those who excel even in their secular studies, unlike those who study in the public schools. And be not concerned about this libel, even though it is published in a newspaper well-known for haters of Israel and those who fear the Lord.”

Connecting the Iggerot

R. Feinstein was renowned for his integrity and commitment to the truth. R. Yaakov Yisochor Rosenberg recalls that when he was a student at the Yeshiva of Staten Island (founded by R. Reuven Feinstein) he heard R. Moshe Feinstein remark that of all the wrongs that the Bolsheviks inflicted upon him there was one thing he could not forgive—that they coerced him under the threat of death to lie, thereby forcing him to transgress “you shall distance yourself from falsehood” (Exodus 23:7) and compromise his integrity (Darkhei Moshe, vol. 1, p. 271). His insistence on truth was evident from his halakhic rulings, such as his adamance that a mashgiah may not grant a Kosher certification to an establishment unless he actually remains there to observe the cooking process. The public collectively pays a premium for kosher food and therefore expect that the agencies that provide these guarantees are truly ascertaining the kashrut of the establishments under their purview (Iggerot Moshe, Y.D., vol. 4, #1:8).

True to the topic of our responsum, R. Yosef Dovid Korbman attests that when he too was in Yeshiva of Staten Island, he witnessed two high school students ask R. Feinstein if they may look over at their classmates’ test paper during an exam so that they may salvage the time spent studying on Torah learning instead. R. Feinstein replied “I know what counts as bittul Torah, and I’m telling you that this is forbidden” (Darkhei Moshe, vol. 1, p. 171). R. Aharon Felder reported that there was once a Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem student who refused to attend his secular studies classes, contending that he wished to study Torah all day. Seeing that he was unsuccessful in persuading him otherwise, the principal asked R. Feinstein to speak to the young man. When they met, R. Feinstein told him, “I am not telling you that you are obligated to go study secular subjects. But this I will tell you—if you wish to remain in this yeshiva then you are required to attend your secular studies classes as they are a part of the yeshiva’s curriculum” (Reshumei Aharon, vol. 2, p. 3).

As we may have gathered, another important topic that emerges from this discussion is R. Feinstein’s approach to secular studies. And here we find a marked difference between what he said vis-a-vis high school and college education. The subject line of a noteworthy responsum (Y.D., vol. 4, #34) reads “young men who wish to abandon (la’azov) the yeshiva in order to study at an college to prepare themselves for medical studies—should they be influenced to remain in yeshiva?” He employs the first verse in Psalms “Happy is the man who has not followed the counsel of the wicked” and asserts that many invoke the rabbinic principle that “it is forbidden to rely on a miracle” to justify the premature departure from the study hall under the pretext of earning a livelihood. He declares that this is what the Psalmist refers to by “the counsel of the wicked”—advice which disguises itself under the veneer of piety.

While R. Feinstein did not permit cheating to salvage time for Torah learning, leaving yeshiva altogether certainly seemed to constitute bittul Torah in his eyes (see Kol Ram, vol. 2, p. 259). In a separate responsum (Y.D., vol. 3, #82) addressed to principals and heads of yeshivot, he identifies additional nefarious elements associated with attending a university, such as exposure to heretical ideas, mingling with the opposite gender, and the “prohibition of setting aside life eternal” for life temporal “which is forbidden even after achieving a degree of mastery of Torah.” Moreover, following the physical and spiritual destruction of the Jewish world it is incumbent upon those who remain to commit themselves to the preservation of Torah learning.

R. Feinstein was not simply challenged to persuade his students, but perhaps more fraught, was convincing their parents about the importance of sustained Torah studies. R. Yeshayahu Portnoy reports that a father once challenged R. Feinstein that the Talmud teaches there are three partners in the creation of a child: The father, mother, and God (Kiddushin 30b). Even if God is on your side, it is still a 2:1 vote and the boy’s parents wanted him to attend college. R. Feinstein responded, “but within each of you is a soul that God has breathed into you, which does not desire for this precious young man to attend such a place” (Meged Givot Olam, vol. 1, p. 79).See the “Reb Moshe” biography (Artscroll, pp. 103-104) for a more elaborate version of this story.

And what if the parents refuse? He reportedly advised that if they insist the student may dig in his heels as well, “for there is no shortage of ways for God to send him livelihood, even if he does not attend the colleges, and does not follow ‘the advice of the wicked’” (Mesoret Moshe, vol. 3, p. 472; note the consistent polemic of the counsel or “advice of the wicked”).

It is important to note that R. Feinstein did not fill his days attempting to dissuade students from attending college. He would only intervene if he knew the individual personally and thought it would be productive (ibid, vol. 4, p. 268). Anecdotally, my wife’s grandfather, R. Bernard Reisner, who spent many years at Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem, attests that R. Feinstein encouraged him to receive a college education to earn a living. This is not contradictory, as it is not unreasonable for a public figure such as R. Feinstein to provide public guidance of a more heavy-handed nature toward a group of yeshiva administrators while still exhibiting flexibility as needed on an individual basis. Indeed, in some instances he advised that it was better to compromise on a mixed yeshiva and college schedule rather than cut oneself off from family and their financial support (ibid, p. 269). R. Aharon Felder (Reshumei Aharon, vol. 1, p. 21) adds that this entire matter would be moot in R. Feinstein’s eyes if the student himself possessed no motivation to remain in the yeshiva. The entire question of how to best navigate the parents’ wishes only begins if their son is actually interested in remaining in yeshiva in the first place.

R. Feinstein’s view on medical studies is a particularly complicated matter. On the one hand, he referred to medical professionals as “agents of God” (O.H., vol. 4, #79) and in Darash Moshe (vol. 1, p, 187) he compares reliance on the expertise of rabbis in matters of Torah with doctors in the medical field. Yet he purportedly remarked that even should someone discover the cure to cancer it would not justify the consequent bittul Torah, as the Talmud (Megilla 16b) states that “greater is Torah study than saving lives” (Meged Givot Olam, vol. 1, p. 23).

Even if that anecdote is too far-fetched to accept at face value, R. Feinstein himself still wrote very critically of Jewish men entering the field of medicine. Returning to the aforementioned responsum in Yoreh De’ah (vol. 4, #34:12), he asserts that due to the extensive time and years invested in attaining a medical degree such an individual will eventually forget the Torah he learned and, needless to say, have little time to progress in his Torah studies in a substantive manner. (Though, he concedes that it may yet be viable for a uniquely gifted individual to accomplish both—perhaps a nod to his son-in-law, R. Dr. Moshe Dovid Tendler.)

He further questions the motives of those willing to expend many years in the pursuit of such a degree, suggesting they might be doing so for prestige or other material motives. He then proceeds to reckon with the Hovot ha-Levavot (ch. 3, Sha’ar ha-Bitahon) which suggests that one should be encouraged to follow their natural proclivities toward a profession that they are drawn towards. To that, R. Feinstein strikingly contends that there is no inherent and natural motivation to become a healer. He bases this in the fact that the Torah only issued “and you shall certainly heal” (Ex. 21:19) as a dispensation to administer medical treatment, thereby indicating that medical intervention is an aberration or departure from the natural order. It follows that the inclination to pursue such a profession must have been developed by extrinsic considerations such as the prestige or wealth that is associated with it. And while in the next section of the responsum (ibid, sub-section #13), he concedes that one has reshut (permission) to enter such a field, he reiterates his skepticism as to whether one can concurrently excel in Torah studies.

We do find R. Feinstein’s willingness to make similar concessions such as in one responsum (Y.D., vol. 5, #38) he advises an individual to choose a public college rather than a Catholic one. And at the end of the ninth volume of Iggerot Moshe, in a section entitled Iggerot Hashkafa (#9), he gave his blessings to Touro College, since they had committed themselves to avoiding heretical content and offered single sex classes. He understood the obvious necessities of earning an income and agreed that if a college degree could be sought in a religiously appropriate manner it would be permissible, as long as it did not tempt the yeshiva student from prematurely terminating his formal Torah studies.

With that being said, R. Feinstein maintained that people who dedicate their time primarily to other pursuits, despite making time to learn, “are certainly upstanding individuals (anashim kesheirim), but it is implausible to classify them as bnei Torah” (Iggerot Moshe, Y.D., vol. 4, #34:15). A striking (and perhaps even perplexing) report was made by R. Reuven Feinstein (Pirkei Shalom, p. 170) who related that his father remarked that while he permitted attending college (under limited conditions) in order to earn a livelihood, since it is now possible to earn a living through teaching Torah, there is no longer a dispensation to discontinue one’s Torah studies. This certainly has implications for R. Feinstein’s responsa on living a kollel lifestyle, which we will address in an upcoming column.

Reception to the Iggerot

Fortunately, I have not found any prominent posek who disagreed (at least publicly) with R. Feinstein’s unequivocal opposition to cheating on exams. Many traditional halakhic authorities also shared his misgivings about attending universities. For instance, when R. Menashe Klein was asked about the permissibility of cheating on a college exam, he initially replied, “it is difficult for me to even write [an answer to the question], for if I address whether it is permissible or forbidden then people will glean that it is fundamentally permitted to attend colleges or universities. But for me, this very matter is already questionable, for the very attending of a college is already [inherently] forbidden” (Mishneh Halakhot, vol. 7, p. 285).

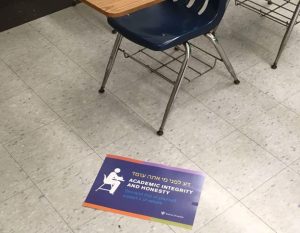

To step back for a moment, we might be appalled at the need for the preeminent halakhic authority to issue a proclamation against cheating in the first place. Certainly –any respectable Jew should be able to answer this without needing to refer to the pages of a Shulhan Arukh. Moving to our own time, Rabbi Jeremy Wieder, in a condemnation of widespread cheating at Yeshiva College, cited R. Feinstein’s responsum and lamented that “it is almost a chilul Hashem [desecration of God’s name] that it had to be written” in the first place (transcribed in The Commentator 67:4 [November 10, 2002]).

Reflecting on the Iggerot

Despite claims made by some, clearly R. Feinstein was knowledgeable about many fields of medicine, science, technology, etc., and drew on the advice of knowledgeable experts, all of which served him in arriving at his sophisticated halakhic rulings. His documented ambivalence toward higher secular education notwithstanding, perhaps much of the confusion about his attitude comes from a conflation between secular knowledge with secular values. However, we may argue that it is quite possible to maintain that one’s philosophy must exclusively emerge from the Torah, while at the same time allowing for external data to inform the analysis. For example, when R. Feinstein consulted R. Tendler on how a battery operated (O.H. vol. 4, #83), he was not incorporating external values but external knowledge to enable him to render an informed halakhic ruling. Surrendering to the will of the Torah is not at odds with knowledge that can be found elsewhere.

More than simply the time expended on secular studies, R. Feinstein’s underlying fear appears to be that the secular becomes primary while the sacred will be relegated to secondary. In Darash Moshe (vol. 1, p. 378), he lamented how just like during the era of Hellenization, “they called the external knowledge light, and even worse they called the theaters and stadiums” in a similar fashion. “They regarded darkness as light, while the light of Torah they called darkness.” To provide a concrete example, we find that in Iggerot Moshe (Y.D., vol. 3, #83) he was adamant that Judaic studies must always be scheduled at the beginning of the day to demonstrate that they are what is primary a Jew’s life. More than the concern for bittul Torah was the philosophical “disregarding of life eternal” for secular, transient pursuits.

In a previous column (“Paging Dr. Cohen”) we noted R. Shlomo Goren’s permission for kohanim to attend medical school, partially on the basis of seeing professional self-fulfillment. While R. Feinstein’s opposition to this position did not reckon with that element, in his responsum about attending medical school generally (Y.D., vol. 4, #34:1), he appears to indirectly dismisses R. Goren’s entire premise, contending that self-fulfillment should emerge from one’s commitment to and study of Torah alone. It can be argued that R. Feinstein was open, to a certain degree, to incorporate secular knowledge into his analysis. However, what he makes clear is that it is the study and adherence of the Torah must always remain our sole raison d’être .

Endnote: I acknowledge my friend and colleague, R. Yair Lichtman, who collaborated with me on a much earlier treatment of this topic. It is interesting to note, that despite R. Feinstein’s vehement opposition to college culture, he notably defended a young woman’s virtue in arguing against a presumption that attending college is ipso facto a surrender to sexual promiscuity (Iggerot Moshe, E.H., vol. 3, #16). See also R. Reuven Feinstein’s Pirkei Shalom (p. 254) for another anecdote regarding parents and university education.

Moshe Kurtz serves as the Assistant Rabbi of Agudath Sholom in Stamford, CT, is the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later.

Prepare ahead for our next column (January 30): Continuing on the topic of R. Feinstein’s engagement with or ambivalence toward general culture, can we put to rest the old question of the Gadol ha-Dor read the newspaper or not? See Iggerot Moshe, Orah Hayyim, vol. 5, #22:3.

1 Comment

In guiding students and their parents with regard to secular studies in general, Rabbi Feinstein clearly took the nature of the individual case into consideration. but lying and cheating is a different matter and required his firm opposition. Thanks.