Unpacking the Iggerot: I.V. Treatment for Yom Kippur

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

I.V. Treatment for Yom Kippur / Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 3, #90

Summarizing the Iggerot

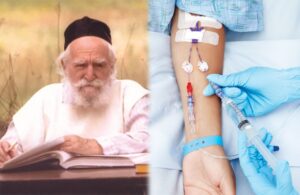

Some people want to exempt themselves from fasting. Others look for a way to opt in, particularly on the hallowed day of Yom Kippur. R. Moshe Feinstein was asked whether one may—and if so, should—accept a medicinal intravenous infusion which would enable them to abstain from consuming food and beverages on this holiest of High Holy Days.

Initially, one might think that in accordance with Rambam’s Mishneh Torah (Shabbat 2:1) that we should view a person’s inability to fast as a regrettable obstacle to be overcome (dekhuya) as opposed to a carte blanche exemption (hutra). The former theory would maintain that eating on Yom Kippur, while necessary for certain individuals, is still a violation of Yom Kippur temporarily superseded for this ill person by the overriding consideration of preserving life. This would suggest that finding ways to become capable of fasting, such as arranging for an I.V., would be commendable, and possibly required.

To that point, R. Feinstein cites the verse which is viewed as the religious proof-text for engaging in medical endeavors: “and shall cause him to be thoroughly healed” (Exodus 21:19). He notes that the Biblical directive is strictly to cure ailments, not to provide drugs that enable one to undertake a fast.

Moreover, he raises the possibility that it may even be forbidden to employ such an intervention. In principle, curing involves the effort of man to subvert the natural order decreed by God, and it is only due to the aforementioned verse that we are permitted to pursue medicinal methods. This is akin to the concept of prayer, which is permitted and mandated despite man’s attempt to alter his divinely decreed fate. However, in the absence of such dispensations, we assume that artificial methods constitute a “contravening of the will of the King” (see Tosafot on Bava Kamma 85a, s.v. she-nitna). Accordingly, it is not simply the case that one would not be required to take the I.V. in order to fast on Yom Kippur, it would actually be forbidden to do so. God only permitted human intervention via healing and prayer. Therefore, there is no mitzva to take the I.V. On the contrary, God’s will is that such an individual should not fast!

R. Feinstein also preempts the suggestion that arguably there would be a unique requirement to undergo medical intervention to enable fasting akin to the mitzva of eating in preparation for Yom Kippur. However, the mandate to have a pre-Yom Kippur meal is conceptually its own independent mitzva. (Even one who is not able to fast still partakes in this meal.) There is an independent obligation to eat prior to Yom Kippur, not to make general preparations for fasting—and certainly not to undergo invasive medical methods to achieve it.

R. Feinstein concludes that even if the use of an I.V. which enables fasting on Yom Kippur does not intrinsically “contravene the will of the King,” it would at minimum not be required. And given that it is not required, it may still be forbidden due to certain external concerns such as the proscription against self-harm (havala) and the needless exposure to medical risk, such as an unforeseen negative bodily reaction to the chemicals. On these grounds, R. Feinstein forbade the implementation of I.V. treatment to enable fasting on Yom Kippur (even if done in advance of the day), and certainly for all other fast days as well.

Connecting the Iggerot

In a later responsum (O.H., vol. 4, #101, sec. 3), R. Feinstein returns to this topic with a slight twist. Unlike his initial ruling which addressed the administering of a drug to enable fasting, he is now asked whether one would be expected to utilize an I.V. just to receive basic nutrition in order to fast. The latter option would be classified as sustenance, which avoids both the halakhic and theological issues of “contravening the will of the King” that are associated with chemical infusions. And at the same time it would still not be in violation of the fast since the sustenance is not entering the body orally, i.e., in the manner of normal consumption (derekh akhila).

R. Feinstein immediately makes sure to note that the question does not get off the ground unless the I.V. is set up prior to Yom Kippur. To insert the I.V. on Yom Kippur itself would ironically swap the less severe infraction of consuming half-measures of food for a procedure (the inserting of the I.V.) which he felt was itself a Biblical violation which also incurs karet (Divine excision). To be clear, in a case of required medical intervention on Yom Kippur, such a procedure is permitted under the general rubric of pikuah nefesh; in this case, however, it is being done only to facilitate fasting, from which the person was already exempt! The question is whether arranging for an I.V. prior to the holiday would be necessary or even appropriate. To that, R. Feinstein strongly cautions against anything which is not “ke-fi ha-teva.” On a pragmatic level, every medical intervention runs the risk, no matter how small, of unexpected complications. But a more subtle point that appears to emerge from R. Feinstein’s responsa is a philosophy of halakha which is resistant to unnecessary artificial intervention that contravenes God and the laws—be they matters of halakha or the natural order—that He has ordained.

A case in point: R. Feinstein rejected the assertion attributed to the Brisker Rav, R. Yitzchok Zev Soloveitchik, that one should utilize a microscope to ensure near-perfect dimensions of tefillin (Y.D., vol. 2, #146). He argued that halakha is determined by what the naked eye can see and does not demand that we utilize the intervention of technologically developed methods.

In a separate responsum he was asked about the permissibility of inducing labor for a pregnant woman (Y.D., vol. 2, #74). Once he had conceded that induction would be permissible under certain circumstances, he was then forced to reckon with whether a woman should proactively schedule her delivery so that the birth and brit not coincide with Shabbat. His response is a clear articulation of the theme we have posited:

The Torah does not require us to seek to employ schemes that are against the natural order (kefi ha-teva) to prevent a violation of Shabbat—even if such a method was legitimate. And this applies to many similar matters…

R. Feinstein did not only oppose artificial methods from a technological standpoint, but from a legalistic standpoint as well. When he was asked about a Jew arranging for his business to be owned by a non-Jew for Shabbat, he responded:

I am not pleased with this—even when I was in Europe—for it is a great circumvention (ha’arama)… For if the court permits such a sale to a gentile, Shabbat would be publicly desecrated. For everyone would conduct themselves leniently and sit in their stores under the pretense (le-ha’arim) that they are just there to provide supervision…

Returning to our discussion of the Tishrei holidays, R. Feinstein adamantly opposed the notion that one could vacation during hol ha-moed without access to a sukka (O.H., vol. 3, #93). The Talmud (Sukka 26a) exempts those traveling for the sake of a mitzva from requiring a sukka at day and night, while those traveling for discretionary purposes, a devar reshut, would only be exempt while they are traveling during the day, but need a sukka when they are lodging at night. R. Feinstein argues that even a devar reshut still presupposes some degree of a necessity, such as traveling for business. He believes that the Talmud was not discussing purely recreational travel, which would require forethought and planning to ensure that a sukka would be accessible. He argues that the literal reading would otherwise lead to a reductio ad absurdum—why would someone not just be able to sleep directly under the stars in their backyard if they find it more enjoyable than their sukka?

In a subsequent responsum (E.H., vol. 4, #32), R. Feinstein qualifies his stance by conceding that if one was spending time in another country such as in Israel (although not only), the constrained time for touring might be sufficient grounds to constitute a more urgent devar reshut, thereby exempting the tourists from requiring a sukka while they are on the go.

At the heart of his stringent stance is that even in the absence of a pure halakhic objection, deliberately placing oneself in a scenario which evades the performance of a mitzva renders one vulnerable to Divine wrath (Menahot 41a). The artificial exempting oneself from a halakha is to be condemned.

What emerges from many of R. Feinstein’s rulings is an uneasiness and, at times, an objection to unnecessary artificial alterations within the halakhic process, be they abstract legal loopholes or concrete technological innovations.

Challenges to the Iggerot

One of R. Feinstein’s objections to the use of intravenous infusions to enable fasting (even prior to the onset of the fast) was the transgression of self-harm (havala). R. Gavriel Zinner in his immense Nitei Gavriel (Hilkhot Yom ha-Kippurim, p. 162) questions whether “self-harm” is the correct framework here. He cites Rashi’s commentary on Shabbat (65a) who understands that women piercing their ears does not constitute harm but is actually a positive action.

The Sefer Mishnat Pikuah Nefesh (p. 138) compounds this challenge by noting that R. Feinstein himself appears to have accepted this reasoning in his permissive ruling on cosmetic surgery (H.M., vol. 2, #66). If undergoing an invasive procedure for purely aesthetic purposes does not violate the mandate against self-harm, it stands to reason that an I.V. should certainly be no worse. Perhaps, given that the self-harm argument was only an ancillary factor, we can suggest that it merely served to buttress his underlying objection to the implementation of unnecessary artificial interventions into halakhic practice.

We should also note that R. Feinstein’s responsa on vacationing without a sukka did not go unchallenged. In his collected insights on Sukka (26a), R. Yosef Shalom Elyashiv is recorded to have objected to R. Feinstein’s break-down of devar reshut into necessary versus recreational travel. He contends that so long as one is on the road he is fundamentally exempt from a sukka under the principle of teishvu ke-ein taduru, that one’s sukka should be regarded no differently than one’s home, which a person travels away from on occasion.

R. Moshe Sternbuch (Teshuvot ve-Hanhagot, vol. 6, #146) further contends that R. Feinstein omitted the critical mandate of simhat ha-hag, celebrating the holiday, from his calculus. The Sefer Yereim (#427) posits an expansive parameter in which essentially anything that makes the holiday more enjoyable is a fulfillment of simhat ha-hag. Moreover, a man has an explicit imperative to ensure that his wife and children enjoy the holiday, which is well documented in the Talmud (Pesahim 109a) and codified by Rambam (Hilkhot Yom Tov, ch. 6). Therefore, even if one were to fundamentally grant R. Feinstein’s delineation between a necessary versus an absolutely discretionary devar reshut, vacationing on hol ha-moed should be classified as the former since it is indeed a mitzva! As the ribbon on top, he quotes the Hazon Ish who remarked that the mitzva is teishvu ke-ein taduru, to treat our sukkot as our living space, not as a prison compound.

We should note that the preeminent Sephardic posek R. Ovadia Yosef (Yehave Da’at, vol. 3, #47) concurred with R. Feinstein’s opinion. He writes that “it is not appropriate to uproot oneself from the obligation of sukka during these days” and applies the verse “Surely I shall take the appointed time; I will judge with equity” (Psalms 75:3). He reads it that God will judge those who do not properly observe his moed, which means generally an “appointed time,” and more specifically, a holiday (see Rashi, ad loc.) Evidently, R. Yosef, at least in this instance, shares R. Feinstein’s overriding philosophical concern for the avoidance of fulfilling the Torah’s commandments.

Reflecting on the Iggerot

While, in theory, a typical halakhic decisor would share similar concerns for workarounds and sudden technological developments, the fact that this was an overriding consideration in a range of R. Feinstein’s rulings is indicative of the premium he placed on authenticity and integrity in the halakhic process—strongly preferring the natural to the artificial.

It is also important to reflect on how R. Feinstein did not simply oppose the gratuitous evasions of mitzvot, but that he strongly advocated for proactively engaging with mitzva performance in a positive manner. In a responsum regarding shehita (ritual slaughter) he questioned whether it was appropriate for the shohet to wear gloves during the process. He remarked that “a person needs to be elated and enamored by the [opportunity] to dirty his hands for the sake of a mitzva, and not to find schemes (tahbulot) to avoid dirtying oneself.” To engage with a mitzva is a privilege.

R. Dovid Feinstein was asked to share the most central lesson that his father wished to impart. He replied that it was the necessity to perform God’s commandments with joy. He noted how many Jews lamented that it is shver tzu zayn a yid, that it is too hard to be a Jew. R. Feinstein observed how such a mentality would be the downfall of Judaism in America. If the younger generation hears day in and day out how challenging it to be a Jew they will be quick to abandon it upon reaching adulthood. Even after the pogroms he endured, the theft and loss of his treasure-trove of manuscripts, the decimation of many of his family members in Europe, the many years of abject poverty, he still insisted that es iz a mekhaye tzu zayn a yid—it is a blessing to be a Jew and to fulfill every edict of the Torah with exuberance (see Darkhei Moshe al ha-Torah ve-Moadim, vol. 2, p. 594).

Endnote: See R. Reuven Feinstein’s commentary on Pirkei Avot, Pirkei Shalom (pp. 66-67), which records a story about when R. Moshe Feinstein himself was connected to an I.V. toward the end of his life and the halakhic challenges that he had to navigate. We should also note that perhaps R. Feinstein’s dedication to the mitzva of sukka was influenced by his father, R. Dovid Feinstein. In keeping with the guidance of the Vilna Gaon, R. Dovid Feinstein forced himself to sleep in the sukka on Shemini Atzeret, even while his health had taken a turn for the worse. Soon thereafter, he passed away from his illness, possibly due to the exertion he put into this mitzva (Man Malkhi Rabbanan, p. 18). We may conjecture whether it was this act of fealty to the mitzva of sukka that helped bring his son, R. Moshe Feinstein, to assume an unwavering stance.

For more on the topic of preventative medicine, see the end of R. Feinstein’s second responsum on the use of I.V. on Yom Kippur (O.H., vol. 4, #101, sec. 3) as well as O.H., vol. 3, #91 where he references R. Yisrael Salanter’s ruling to eat on Yom Kippur in order to maintain a healthy immune system during a Cholera outbreak. Regarding the use of I.V. see also Responsa Teshuvot ve-Hanhagot (vol. 2, #290). And regarding the question of inducing labor to prevent conflict with Shabbat, see Shemirat Shabbat ke-Hilkhata (ch. 32, par. 33), and Nishmat Avraham (vol. 2, p. 105).

It is somewhat puzzling that R. Feinstein made no reference to R. Chaim Ozer Grodzinki’s iconic responsum Ahiezer (vol. 3, #61; pub. 1922) which serves as one of the key sources permitting the use feeding by medical means on Yom Kippur. While R. Feinstein’s style was not to necessarily account for the more recent halakhic literature, we know that R. Grodzinski held R. Feinstein in high regard from a young age (see Man Malkhi Rabbanan, p. 23), and that the feelings were mutual on R. Feinstein’s end. When he was escaping to America he even made a point to stop in Vilna just to receive a blessing from R. Grodzinski (ibid., p. 21).

For more on the nature of ha’aramot in Rabbinic literature, see Letter and Spirit: Evasion, Avoidance, and Workarounds in the Halakhic System by Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman, and Circumventing the Law: Rabbinic Perspectives on Loopholes and Legal Integrity by Dr. Elana Stein Hain.

Moshe Kurtz serves as the Assistant Rabbi of Agudath Sholom in Stamford, CT, is the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later podcast.

Prepare ahead for the next column (after the holidays on October 31): On celebrating a Bat Mitzva (Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 1, #104).

1 Comment

INfusion is out-of-the-question for another important reason. True, when the Torah and Talmud were in first promulgated, norishmebnt was only possible by one’s mouth, and now infusionn is vpossiblre. The ban agaonst rikding a vehicle applies today to motor cars, even electric motor-cars vwithou settingv fires each piston movement, even though animal oppower isn’t nhecessary. So, the ban on food applies to norishment via infusion as well as by mouth. A sick person eating on Yom HaKippurim violates only one commandment, and Torah Law permits him or her to do so for potential saving his or her life. But infusion involves causing another to work, unnecessarily, and that is forbidden.

With the permission of my teachers,

David Lloyd (ben Yaacov Yehuda) Klepper, 92-year-old student, Jrerusalem Hesder Yeshivat Beit Orot, USA Army veteran