Unpacking the Iggerot: Shabbat Timers and Hatzalah

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

Unpacking the Iggerot: Timers and Hatzalah / Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 4, #60

Summarizing the Iggerot

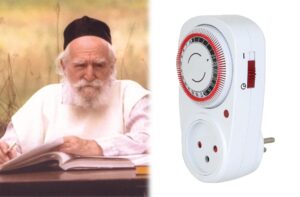

Many recall R. Moshe Feinstein’s creative approach to halakha that produced novel leniencies that became widely accepted by the public. While, on the other hand, his more stringent (and less convenient) rulings often gained less traction and have faded into near obscurity. Such is the case with his 1976 responsum against the use of timers on Shabbat, which opens with a striking formulation:

There is no greater denigration of Shabbat than this. For it is clear that if this existed in the times of the Tannaim and Amoraim (Sages of the Mishnah and Talmud) they would have forbade it, just as they forbade amira le-akum (requesting a gentile to violate Shabbat on a Jew’s behalf).

R. Feinstein claims that the use of a “Shabbat Clock” would have been prohibited by Hazal, either under the category of amira le-akum or conceptually analogous to it, and indeed goes on to suggest that there may even be a Biblical-level issue here as well.

He notes that unlike one who sets a pot on the flame prior to Shabbat, in which the cooking process has already been initiated, in the case of a timer, the melakha only begins on Shabbat itself, which perhaps makes it more problematic. He cites the creative analysis of Nemukei Yosef (Bava Kama 22a) who asks how the Sages mandated lighting candles for Shabbat since every second that it is lit would be akin to constantly rekindling—just like one would be liable for arson when one’s flame travels to burn down another person’s property. This is based on the conceptualization of “His flame is like his arrow”—that when a person releases an arrow, halakha views it as if he is carrying the projectile himself and implanting it directly in its target. Accordingly, when one lights a candle before Shabbat, would it not be considered as if one is constantly rekindling it over the course of Shabbat? Nemukei Yosef answers that the moment the arrow is released halakha imagines as if it has already hit its target and that the shooter’s role is immediately accomplished and thereby terminates. Likewise, when one lights a flame before Shabbat, her role immediately terminates and she would not be liable for producing that flame on Shabbat. Therefore, it follows that setting a timer should be no worse, once the individual has calibrated and set up the timer on Friday afternoon his role terminates and he has no part in what occurs on Shabbat.

Moreover, while in the laws of torts and damages a person’s force is tantamount to a direct act, in the laws of Shabbat that is not necessarily the case. Nevertheless, a force produced by a person should still be more severe than mere words. So while setting a timer may not contravene Shabbat on a Biblical level, it would be, perhaps, more severe than amira le-akum, which is forbidden despite it being transgressed by words alone.

In addition to his analogy to amira le-akum, R. Feinstein asserts that setting a timer would produce an active denigration of the honor of Shabbat, irrespective of whether it is akin to asking a gentile or not.

With that being said, he recognized that even within the parameters of amira le-akum, there was already a leniency on the books for asking a non-Jew to light candles to enable a congregation to continue praying during Neila at the end of Yom Kippur, and this dispensation was further expanded to Shabbat whenever light is needed to facilitate communal prayer. Rema (O.H. 276:2) codifies a leniency for asking a gentile to light for a meal celebrating a brit or marriage on Shabbat as well. Since R. Feinstein’s main argument was that timers are akin to amira le-akum, it follows that they should not be regarded more stringently. Therefore, he permitted timers to be used strictly for operating the lights on Shabbat, while cautioning against expanding it any further.

Connecting the Iggerot

Interestingly, it appears that R. Feinstein took some time to develop his categorical opposition to timers, as in an earlier 1972 responsum (O.H., vol. 4, #91), he only prohibits adjusting a timer on Shabbat, which implies approval for it being set up before Shabbat begins. Likewise, in 1973 he ruled that adjusting a timer on Shabbat would constitute a Biblical violation, while simply preventing it from activating at all would be in violation of muktza (Y.D., vol. 3, #47). Once again, he only acknowledges an issue with engaging with the timer on Shabbat, while seemingly approving of its use should it be set up ahead of time. It was only a few years later, in 1976, that he sought to categorically do away with their use altogether. In fact, by 1982, he went so far as to rule that one may not eat food cooked on Shabbat by using a timer, even if he is dining by someone else who is lenient in that regard (O.H., vol. 5, #24.5).

Nonetheless, he was willing to cede ground on a few details. Firstly, as we noted, he concedes in our initial responsum that a timer may be used for activating and deactivating lights, akin to permitted cases of amira le-akum. It is also recorded in Sefer Mesoret Moshe (vol. 1, pp. 96-97) that he was not opposed to a thermostat, since it is regulated by external shifts in the environment rather than being directed to activate at specific times. (Though, the fact that modern thermostats can indeed be set on specific schedules raises a question about whether R. Feinstein would maintain this exception.) Finally, a particularly surprising 1979 responsum to R. Ephraim Greenblatt (O.H., vol. 4, #70.6) permits the use of an alarm clock to wake up an indivdual for prayers on Shabbat morning, provided the noise-level is limited to his room. It is striking that R. Feinstein only reckons with the principle of avasha milta, the Rabbinic proscription against disturbing noises (e.g., a mill), while his general opposition to setting a timer for Shabbat remains noticeably absent.

While the topic of timers serves as an instance of a uniquely creative stringency in Hilkhot Shabbat, in the following year, R. Feinstein published one of his most radical leniencies in the same area of Jewish law (O.H., vol. 4, #80). He embarks on an extensive analysis which ends up permitting members of the Hatzalah volunteer ambulance corps to drive back from their calls on Shabbat—essentially allowing the transgressing of what would otherwise constitute a Biblical violation of igniting a fire (due to the combustion engines). His thesis boils down to a radical re-reading of how the Gemara parses the following Mishnah in Eruvin (44a):

One who was permitted to leave [his Shabbat limit] and they said to him: The action has already been performed, he has two thousand cubits in each direction. If he was within [his original] limit, it is as if he had not left [his limit]. All who go out to save [lives] may return to their [original] locations [on Shabbat].

The Mishnah appears to contain an internal contradiction. It initially grants up to two thousand cubits to those who have left on a life-saving mission, while the last sentence appears to allow returning with no limitations on the distance. One suggestion provided by the Gemara is that the Mishnah is distinguishing between a scenario where the gentiles are in power versus when the Jews are in power.

Most poskim understood the Gemara to permit the Jewish rescue forces to return with no limits when the gentiles are in power, as such circumstances would engender a continued threat of violence. While, when the Jews are in power (or have a government providing security), there would not be a justifiably imminent threat to constitute pikuah nefesh and permits a carte blanche returning of any distance.

R. Feinstein, based on Tosafot (Eruvin 44b, s.v. kol ha-yotzin) and Rashba (Beitza 11b, s.v. be-pelugta) understands that the Gemara’s distinction is not about threat levels but about ensuring that the responders are not deterred from going out on future live-saving missions. Actually, it is when the Jews are in power, and the security operation is generally brief, that the responders would expect to be able to return home—and to not be permitted to do so would make them think twice before going on future calls. This is what the Talmud (Beitza 11b) calls hitiru sofan me-shum tehilatan, that a later infraction is permitted to ensure a response is initially taken. This would not be limited to military or security forces, but to midwives, medical professionals, and the EMTs of modern day Hatzalah—and this would permit the breaching of tehumin, operating a vehicle, and other pertinent Biblical violations of Shabbat. (See also Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 5, #25 for an elaboration on if and when to ask a gentile to drive a Hatzalah member back from a call.)

Reception of the Iggerot

The issue of Shabbat timers and Hatzalah workers respectively represent radical rulings from R. Feinstein on both the stringent and lenient extremes. And each one received a rocky reception from his contemporaries and subsequent halakhic decisors. For instance, Shemirat Shabbat ke-Hilkhata (13:23), a normative source of Shabbat guidance, authorizes the use of timers without so much as a nod to R. Feinstein’s objection. R. Dovid Ribiat, in his The 39 Melochos (p. 137) also writes that normative practice has not adopted R. Feinstein’s stringency. However, he does conclude:

While many Poskim do not accept this strict ruling to its full measure (indeed most people set air conditioners to timers), one should nevertheless take heart to consider that operating all sorts of appliances via pre-set timers does seem to degrade the spirit and special character of Shabbos.

Some of the major poskim took issue with R. Feinstein’s attempt to expand the Rabbinic restrictions of amira le-akum to include use of timers (aside from lights, as noted). R. Ovadia Yosef (Yabia Omer, vol. 10, O.H., #26:6), citing Sefer Yedei Hayyim (p. 200), proclaims that the modern day rabbinate does not possess the power to create novel halakhic edicts. He remarks, “in my humble opinion, I am not afraid to say that this [Shabbat timers] is absolutely permissible, and there is nothing to be concerned about.” In a similar fashion, R. Yaakov Kamenetsky quipped that even the expansion of Rabbinic enactments is in the spirit of Reform (Ma’arkhei Lev: Iyyunim u-Virurim be-Shimush Makhshir Hashmali Madorni be-Shabbat, p. 220, fn. 12).

In terms of the content of their claims, it is worth looking back at what R. Feinstein actually wrote in his responsum: “[Timers] should not be permitted since they are a matter that is worthy of being forbidden.” R. Feinstein surely did not delude himself into thinking that he could expand a Rabbinic enactment. Indeed, in another landmark Hilkhot Shabbat ruling he writes that a kli shlishi categorically does not cook its contents as “we cannot say [i.e., legislate new laws] on our own, but from tradition alone” (O.H., vol. 4, #74).

While on the matter of timers, he was stringent, the matter of Hatzalah prompted a different, yet not wholly dissimilar form of pushback. R. Ovadia Yosef, once again, outright disregarded R. Feinstein’s ruling and asserted that it could not be relied upon even as a leniency (Hazon Ovadia: Shabbat, vol. 3, p. 254). This is in contrast to R. Eliezer Waldenberg who, while still disagreeing with how far R. Feinstein went, still concluded that he can be relied upon and that anyone who opts to do so should not be chastised for it (Tzitz Eliezer, vol. 21, #59).

Perhaps, the most noteworthy rejoinder came from R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (Minhat Shlomo, vol. 1, #8; cf. Kovetz Moriah, 1980), both in terms of content and form. He charges that R. Feinstein’s concern for discouragement to go out on future calls leads to a reductio ad absurdum: Perhaps a doctor should be able to light a candle on Shabbat to find his freshly pressed medical coat, lest he be deterred by the embarrassment of appearing unkempt in public. Also, perhaps a doctor should be permitted to eat on Yom Kippur so that he can remain in top condition to serve a patient who might need him. Where would we draw the line?

Despite his scathing polemic against R. Feinstein’s reasoning, he appended a footnote to the beginning of the responsum in which he explains that he only published it upon receiving explicit approval from R. Feinstein. Similar to R. Kamentsky, these were “disagreements for the sake of Heaven,” not an ad hominem battle between personalities. In R. Finkelstein’s Reb Moshe biography, he records from Hiko Mamtakim (vol. 2, p. 34):

Once, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach stood the entire time while speaking on the phone, though his son R’ Baruch, out of concern for his father’s health, asked that he be seated. Upon hanging up the phone, Reb Shlomo Zalman said, “How can one sit when speaking to Reb Moshe?”

R. Feinstein passed away on the Fast of Esther 1986, and was set to be buried in Eretz Yisrael on Shushan Purim day, which is when the holiday is observed in Jerusalem. Despite contravening the festive nature of the day, R. Auerbach instructed that R. Feinstein’s coffin be brought through the city and that a full funeral befitting the Rabbinic leader of the generation not be minimized in any manner—even on the joyous day of Purim. He further instructed that any parties and festivities on the night of Purim should not be held with the same gusto as they would normally be done (see Halikhot Shlomo, Moadei Hashana, Tishrei-Adar, ch. 19, par. 30, pp. 345-346, fn. 91). Their fiery and unrelenting disagreements in matters of high stakes halakhic matters did not impede their relationship; perhaps it may have even contributed to it.

Reflecting on the Iggerot

R. Feinstein himself also demonstrated the trait of arguing for the sake of Heaven. R. Reuven Feinstein (Pirkei Shalom, p. 233) reports that when his father and R. Yosef Eliyahu Henkin’s disagreement on non-Orthodox marriages was out in the open on the pages of HaPardes, people frantically begged R. Feinstein to find some way to make amends with R. Henkin. To which he responded that he did not understand their concern: R. Henkin thinks differently and he is therefore obliged to make his case based on his scholarly convictions.

In a similar fashion, R. Feinstein allayed the concerns of a Torah scholar living in Bnei Brak who was afraid to dispense halakhic rulings that were at odds with the Hazon Ish. He reassured him that, on the contrary, it is an honor to the the Hazon Ish to invoke and analyze his rulings, even if the presenter does not ultimately rule in accordance with it (Iggerot Moshe, Y.D., vol. 3, #88).

R. Aharon Felder reports that when he asked R. Feinstein what he thought about R. Avraham Yitzchak Hakohen Kook, one of the patriarchs of modern Religious Zionism, he responded “one needs to know that just because one does not agree with the philosophy and opinion of an adam gadol it does not diminish his status as an adam gadol” (Reshumei Aharon, vol. 1, p. 28).

On another occasion, when a younger R. Menashe Klein apologized for disagreeing with him, R. Feinstein responded, “it is unnecessary for you to apologize for differing with me, for it is the way of the Torah to clarify that which is the truth. Heaven forfend for one to remain silent if they think differently, whether leniently or stringently: (Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 1, #109).

And this brings us back to one of the key themes of this essay. That for R. Feinstein, it was not about being stringent or lenient, but about attaining the truth. Seeking the truth can require a fresh look at a Gemara and also a willingness to consider broader jurisprudential considerations, as R. Michel Shurkin remarked in an interview:

A common impression upon learning some tshuvos of Rav Moshe is that he was a meikel, someone who tended towards leniencies. “It’s simply not true,” states Rav Michel flatly. “When it came to certain fertility-related issues, he was extremely stringent….And he would rule from hashkafah sometimes, prohibiting the use of certain devices on Shabbos because using them wouldn’t be in the spirit of Shabbos.” Even when Rav Moshe held that something was permissible, there were times he didn’t want to issue that ruling to someone he felt might not stick to the spirit of Shabbos if he gave a heter.

The misconception of R. Feinstein as simply a “meikel” is further challenged by the following story in R. Finkelstein’s Reb Moshe biography:

In the formative years of Hatzolah, the world-renowned volunteer medical emergency service, it was Reb Moshe who established the halachic guidelines for responding to calls on Shabbos. At a meeting between rabbanim and Hatzolah coordinators, a rav suggested to Reb Moshe that he was being lenient with regard to Hilchos Shabbos. Reb Moshe rose and declared, “I am not a meikil in Hilchos Shabbos; I am a machmir in pikuach nefesh (saving a life).” A short time later, Reb Moshe sent a message to Rabbi Heshy Jacob, coordinator of the Lower East Side’s Hatzolah division, asking if he could become an official member of Hatzolah. Rabbi Jacob asked Reb Moshe’s grandson, Rabbi Mordechai Tendler, to explain the request. Rabbi Tendler said, “Your work is pikuach nefesh and the Rosh Yeshivah would like to be a part of your work.” Rabbi Jacob replied that as Hatzolah’s supreme halachic authority, Reb Moshe surely was a member (pp. 194-195).

In our next column on the Manhattan eruv we will observe, yet again, the inaccuracy of classifying R. Feinstein as a “meikel.” He produced both remarkable leniencies and stringencies, based on his incisive analysis and his ability to render a halakhic ruling that was fit for the masses. Prepare ahead: Iggerot Moshe, O.H., vol. 1, #138-139.

Endnote: On the matter of timers, see also Minhat Shlomo (vol. 1, #13), and also see Meged Givot Olam (vol. 2, p. 64) for an analysis of R. Feinstein’s Hatzalah ruling. Many more references can be found in Petihat ha-Iggerot on timers (pp. 254-256) and Hatzalah (pp. 280-283) respectively. For an interesting modern application of R. Feinstein’s approach to timers and the like, see R. Aryeh Lebowitz, “A Coffee Drinker’s Guide to Shabbos,” Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society (LXXVII). With the further development of “smart home” technology, it will be interesting to observe if modern poskim may adopt a similar approach to R. Feinstein’s responsum on timers. Only time will tell.

Moshe Kurtz serves as the Assistant Rabbi of Agudath Sholom in Stamford, CT, is the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later.