Unpacking the Iggerot: Paging Dr. Cohen?

Read more about “Unpacking the Iggerot” and see the archive of all past columns.

May a Kohen Become a Doctor? Iggerot Moshe, Y.D., vol. 3, #155

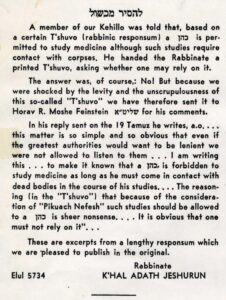

In Autumn of 1974, the “Mitteilungen” or community announcements of R. Shimon Schwab’s synagogue, K’hal Adath Jeshurun, opened with a strident message:

A member of our Kehillo was told that, based on a certain T’shuvo (rabbinic responsum) a kohen is permitted to study medicine although such studies require contact with corpses. He handed the Rabbinate a printed T’shuvo, asking whether one may rely on it.

The answer was, of course: No! But because we were shocked by the levity and the unscrupulousness of this so-called “T’shuvo” we have therefore sent it to Horav R. Moshe Feinstein shlita for his comments…

The bulletin subsequently summarizes and provides the full text of R. Feinstein’s response to R. Schwab (Yoreh De’ah, vol. 3, #155), with notable appellations befitting of his stature.

Like R. Schwab, R. Feinstein was similarly flabbergasted and proceeded to launch a full-throated repudiation of this anonymous “kuntres” being circulated. He opens up his responsum with a programmatic statement of maintaining the halakhic system’s integrity. The Talmud (Yevamot 102a) relates that:

Rabba said [that] Rav Kahana said [that] Rav said: If Elijah [the Prophet] should come and say: One may perform halitza using [a soft leather] shoe, [the Rabbis] would listen to him. [But if he says:] One may not perform halitza using [a hard leather] sandal, they would not listen to him, for the people already have [established] the practice of [performing halitza] using a sandal.

R. Feinstein notes that there is an already established axiom that “the Torah is not in Heaven.” Therefore it is self-understood that even if Elijah prophesied that there should be a shift in halakhic practice, it would have no bearing. Rather, the novelty of this Talmudic passage is that it conveys that even if the prophet asserted based on his erudition and expertise in Torah knowledge that we should alter the procedures for halitza it would still not be heeded. Once the customary halakhic practice has been established a later authority may not (easily) upend it. With that premise, R. Feinstein expresses how appalled he is that some rabbi would attempt to disregard longstanding settled law which regulates how to maintain the sanctity of kohanim.

Moreover, R. Feinstein shifts to near ad hominem critique, expressing doubt as to the credentials of the author of this mysterious kuntres. He argues that the frivolous halakhic errors made “testify that this author is not connected to Torah nor to wisdom.”

The first erroneous assumption of the kuntres, in R. Feinstein’s view, is that since all kohanim nowadays are presumed to have already been exposed to tumat meit, spiritual impurity obtained from proximity to a corpse, it would obviate (or at least mitigate) the problem of subsequently interacting with a cadaver during medical studies. In fact prior exposure to tuma does not permit a kohen to re-engage with it again.

R. Feinstein’s second, and more fundamental objection is the misapplication of pikuah nefesh, the mandate to preserve life. The author apparently argued that since medical professionals save lives, and the mitzva of preserving life supersedes almost every mitzva, it follows that kohen may—or should—disregard the concern of tuma for the greater priority of pursuing pikuah nefesh.

However, R. Feinstein contends that this is a fallacious. He draws an analogy to the mitzva of giving charity: One is not obligated to become wealthy in order to become a philanthropist and be able to give more charity. Rather, one is only required to act in accordance with his or her current resources. Likewise, there is no mitzva to become a doctor in order to save lives. Only once someone already possesses the medical knowledge to treat patients would the resultant obligation (and opportunity) of pikuah nefesh set in. The logic of the kuntres otherwise leads to a reductio ad absurdum. If a kohen should study medicine to save lives, then, by the same virtue, all Jews should be obligated to at least apply for medical school so that they too can save lives! Yet, we have no precedent in halakha or practice which would indicate such an expectation—no doubt to the chagrin of countless Jewish mothers. Moreover, among his other final objections, R. Feinstein argued that there are already many non-Jewish non-kohanim (Jews and Gentiles) who can fill these physician roles.

However, we should note that R. Feinstein does not reserve his ire exclusively for the anonymous rabbi peddling these faulty halakhic arguments, but also includes strong words of rebuke for those who would seek to latch on to it to justify what he saw as flimsy leniencies. He remarks that “if [the kohanim] wanted to know the true law, they know from whom to inquire.”

Connecting the Iggerot

From the responsum just reviewed, we can be left with the impression that R. Feinstein was absolutely uncompromising on matters of kohanim in medical settings. In no uncertain terms, he condemned the idea of a kohen attending medical school, due to concern for tumat meit. Interestingly, however, he adopts a more flexible stance in two separate, yet related, cases.

From the responsum just reviewed, we can be left with the impression that R. Feinstein was absolutely uncompromising on matters of kohanim in medical settings. In no uncertain terms, he condemned the idea of a kohen attending medical school, due to concern for tumat meit. Interestingly, however, he adopts a more flexible stance in two separate, yet related, cases.

In an earlier column, “Never Go Against the Family,” we noted that R. Feinstein permitted a kohen to visit his wife’s relatives in the hospital if refraining from doing so would strain their relationship (Yoreh De’ah, vol. 2, #166). His rationale was that in America, where most patients are not Jewish, one could rely on the position that only Jewish corpses generate tumat ohel, ritual impurity from being under the same “tent” or enclosed area as a corpse.

In another responsum (Y.D. vol. 1, #248), he gives recommendations for how a kohen can serve as a general employee at a hospital. He bases it on two factors: First, if the hospital only serves a minority of Jewish patients we can operate based on the aforementioned rationale. Moreover, we can apply the principle of rov holim le-hayyim, that a person who falls ill has a presumption of remaining alive. Therefore, so long as the kohen can arrange for the hospital to inform him and permit him to leave when they know that a Jewish patient passes away he may continue to be employed there. (Many hospitals in Israel have such systems for their kohen employees and visitors.)

The key distinction between the two more permissive responsa versus R. Feinstein’s ardent opposition to kohanim attending medical school, is that the latter two assume that the kohen will merely be under the same roof as a corpse. In the case of medical training, the kohen would have to interact directly with a cadaver, thereby exposing himself directly to tuma. For R. Feinstein, and the majority of halakhic authorities, that is a step too far.

Challenges to the Iggerot

All of this, of course, beckons the question: What room is there (if any) to differ with R. Feinstein’s position on kohanim enrolling in medical school and pursuing a noble career in medicine? Is there a recourse to what seems like an open-and-shut case?

R. Shlomo Goren, who served as head of the IDF rabbinate and Chief Rabbi of Israel, in a letter to a R. Larry Waxman of Yeshiva University (published in, Asya 18 [April 2002]), proposed a novel method to permit kohanim to attend medical school. As R. Feinstein himself acknowledged in the two aforementioned responsa, he proposes that due to pikuah nefesh, kohanim may rely on the opinion of R. Shimon bar Yohai who held that non-Jewish bodies will pose no issue of tumat ohel. However, this still does not avail kohanim who would be required to interact directly with a cadaver during dissection.

For this, R. Goren presents two important data points: The first principle is the assumption that once a kohen becomes connected to tuma, there would be no prohibition of further exposing himself to tuma since he has not effectively increased his level of exposure (see Ra’avad to Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Nezirut, 5:15-17).

Secondly, there is a principle that “a sword is akin to a corpse.” The highest tier of tuma is a corpse, known as the “father of fathers of tuma.” Generally the level of tuma degrades with every subsequent degree of separation from its origin. Metal implements, however, possess a unique quality that they retain the same heightened state of tuma as the corpse. Though, oddly enough, the Rema (Y.D. 369:1) rules that while kohanim are certainly forbidden to expose themselves to tumat meit via a corpse, they need not avoid contracting it from a metal implement.

R. Goren proceeds to combine these two leniencies to devise a remarkable workaround. If a kohen is given a metal bracelet which retains the highest state of tuma, he would not be effectively doing anything wrong by touching a cadaver during dissection—since he is already wearing the ritually impure bracelet. It’s a clever construct because it enables the kohen to initially connect himself to tuma permissibly, which then renders him “impervious” to the ramifications of exposing himself to any additional tuma from an actual corpse.

While it is an innovative argument, it appears to be sound. On what basis would R. Feinstein, R. Schwab, or others disagree?

One issue is that R. Goren predicates part of his argument on the position of Ra’avad (and other Medieval scholars) who adopt a more permissive approach to re-exposing oneself to tuma. However, R. Feinstein, in an unrelated responsum (Y.D., vol. 1, #230) articulates that normative halakha is in accordance with Rambam on this issue and that it would be forbidden ab intio for one to further expose himself to tuma, even in the event that he is already in direct contact with a corpse. Certainly then, if one is wearing a tamei bracelet, it would still be forbidden to proceed to interact with a corpse.

R. Hershel Schachter, in Be-Ikvei HaTzon (pp. 237-238), directly addresses the claims of “hakham ehad,” a clear reference to R. Goren. He notes, based on R. Chaim Ozer Grodzinski (Ahiezer, vol. 3, #65) and R. Elchonon Wasserman (Kovetz Shiurim, vol. 2, #41) that there are two distinct prohibitions at play: To contract tuma and to bring oneself near tuma.

Oftentimes this is a moot distinction because in order to become tamei one needs to come within proximity of it. However, there are cases in which one could come within the vicinity of tuma while not necessarily contracting it. For example, there is a question about whether the pregnant wife of a kohen may enter a cemetery (see Rokeiah #315 and Magen Avraham 343:2). Even though her potentially male fetus would not become tamei, since he is enveloped within her womb, it would still constitute an issue of coming within the vicinity of tuma.

On this basis, R. Schachter argues that while a metal bracelet shares the maximum tier of tuma as a corpse, they are not perfectly analogous. Even if the kohen is not contracting additional tuma, he is in violation of drawing himself closer to tuma by coming in contact with an actual cadaver.

Reflecting on the Iggerot

While some suggested that the anonymous kuntres R. Schwab and R. Feinstein referred to was penned by R. Goren, we should note that the dates do not work out. R. Feinstein’s rebuttal was published in 1974 while R. Goren’s responsum is reported to have been published only in 1981. Either there was an earlier draft of R. Goren’s responsum or there was another author who advanced similar arguments.

But, according to those who suspect it was R. Goren’s hand behind the kuntres, it is worth noting a distinction between his actual argumentation versus how it is represented in Iggerot Moshe. R. Feinstein objects to the rationale of potential future pikuah nefesh as grounds to permit kohanim to study medicine. However, R. Goren only applies the principle of pikuah nefesh (as well as human dignity and other meta-halakhic concepts) as an impetus to rely on well-documented lenient interpretations, such as that of the Ra’avad. R. Goren did not simply invoke pikuah nefesh and then call it a day—his leniency emerges from within the traditional halakhic literature on the topic of tuma. While I suspect R. Feinstein would have rejected this in any event, such a nuance deserves mention.

To understand R. Feinstein’s vehement opposition, we have to appreciate that there was more at stake than the narrow question of kohanim attending medical school. The notion that any layman could simply procure a random kuntres from the ether, circumvent the rabbinic establishment, and overturn generations of settled law was unconscionable. (The applications to contemporary trends in which halakhic conclusions are reached by laypeople on Internet chat rooms, emails lists, or blogs are a clear case-in-point that is worthy of further exploration.)

On the other hand, we can also sympathize with the unique circumstances that R. Goren faced. Unlike a predominantly non-Jewish country, like America, which will survive without kohanim serving in the medical profession, for the State of Israel to automatically disqualify all of its kohanim from the outset would put a marked dent in the national talent pool.

While R. Feinstein unequivocally forbade kohanim from attending medical school, there is perhaps room, even within his own approach, to permit related occupations. Dr. Fred Rosner and R. Dr. Moshe Tendler, in their book Practical Medical Halachah (third revised edition), adopt R. Feinstein’s halakhic stances and, naturally, codified his opposition to kohanim attending medical school. What is interesting to note is that they posited a leniency for dentistry, a topic which R. Feinstein did not explicitly address:

If, however, the dental student can avoid actual dissection and attend only as an observer and if his early dentistry training does not include a human skull with its dentition, then there is little halachic objection to a kohen studying dentistry. This restricted permissibility rests upon the fact that in the present era we follow the lenient halachic ruling that a non-Jewish corpse does not convey ritual defilement to people in the same room who have no direct contact with it. Unlike the physician, the dentist is not usually involved with dying patients, death certificates, the mortuary, etc., which pose seemingly insoluble problems to a physician who is a kohen (17).

We can further surmise that if it becomes more commonplace to use virtual dissection tables, 3D models and synthetic cadavers, perhaps even those who subscribe to R. Feinstein’s position would no longer need to unequivocally oppose kohanim attending medical school.

A concluding observation: There is a certain beauty in recognizing a unity within the thought and writings of a great scholar such as R. Feinstein. In addition to his halakhic magnum opus, Iggerot Moshe, and his discourses on the Talmud, Dibberot Moshe, a portion of his homilies and teachings on the Torah are preserved in Darash Moshe. R. Feinstein comments on the verse “and they shall judge the people with righteous judgment” (Deut. 16:18):

For the mitzva to become a judge who is an expert in Torah that is not prone to err is part of the [general] mitzva of Torah study that is incumbent upon every man to learn the entire Torah and that he also become an expositor of the laws of Israel. For even though the mitzva of charity does not require one to involve themselves in a particular venture or labor that will make them wealthy so that they may give [more] charity. Only if one is already wealthy is he obligated [to give more]. Moreover, there is no obligation to study in order to become a healer. Only if one is already knowledgeable in medicine is he then mandated to heal others (Darash Moshe, vol. 2, p. 96).

R. Feinstein subsequently proceeds to distinguish Torah study from other occupations. Unlike philanthropy and medicine, one is obligated to attempt to become a Torah scholar who is capable of dispensing halakhic rulings, even if he is not yet learned. And if one makes a good-faith attempt, God will absolve them if they did not manage to hit the mark.

What is intriguing about this brief idea tucked away in Darash Moshe is that R. Feinstein employs precisely the same examples as his responsum against kohanim attending medical school: Charity and medical study. It would not be surprising if this insight on the parasha was formulated around the same time as the matter of kohanim attending medical school was being adjudicated. And, remarkably, this piece takes the responsum in Iggerot Moshe to its final stage, by contrasting worldly endeavors—noble as they may be—with the unique spiritual pursuit of Torah study which is incumbent upon everyone to strive for, as we pray every day “it is our life and the length of our days.”

Endnote: For another noteworthy responsum on the laws of tuma, see Iggerot Moshe (Y.D., vol. 1, #249), regarding kohen relatives accompanying the funeral casket. For additional perspectives on this topic see Responsa Mishneh Halakhot (vol. 4, #146, and vol. 6, #205), Responsa Teshuvot ve-Hanhagot (vol. 1, #677), and a fascinating work called Sefer Tziyon le-Nefesh Tzvi, an extensive treatment of whether kohanim may visit the gravesites of rabbinic sages (see pp. 208-209 in particular, where he refers to Iggerot Moshe, Y.D.., vol. 1, #230). For an overview of issues related to these topics see Alfred S. Cohen, “Tumeah of a Kohen: Theory and Practice,” Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society 15 (1988). My thanks to R. Reuven Klein for bringing the latter source to my attention and separately to Messrs. Gedaliah Wielgus and Eli Schwab for providing me with the scan of R. Feinstein’s handwritten responsum to R. Schwab and the subsequent announcement that was sent to K’hal Adath Jeshurun, as referenced at the beginning of this essay.

Moshe Kurtz serves as the Assistant Rabbi of Agudath Sholom in Stamford, CT, is the author of Challenging Assumptions, and hosts the Shu”T First, Ask Questions Later.

Prepare ahead for the next column (September 12) on kohanim flying on planes transporting bodies for burial in Israel / Iggerot Moshe, Y.D., vol. 2, #164.